Top 10 Lists honestly are usually pretty easy for me. But 2004 is different. Usually, it is simple because there are at least 2-3 movies that stick with me immediately as the best of the year. But 2004 is big, brash, and bold. But it is also sometimes very, very bad. That being said, there are more than a handful of excellent movies, many of which I caught up with over the past few years.

But let’s jump into the Top 10 of 2004 (subject to change from minute to minute)

10. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Look, there is absolutely no way I was going to create a list and not include this. When you put an actual great director like Alfonso Cuaron in charge of a franchise film, you can approach greatness. It certainly helps that the young actors have matured a bit, both in age and in acting experience, but that does not explain the leap in quality. The subject material is noticeably darker helps, as does the absolutely perfect casting of Gary Oldman as Sirius Black. But a few directorial choices stand out as well. The introduction of the Dementors (long-awaited by fans of the book series) somehow surpassed expectations. Their first appearance, mainly signified by a loss of light and brief glimpses of the horrifying creatures through a window, is not only effective but smart. Revealing more and more of them until the climax allows fear and disquiet to grow in the audience as we connect with the characters. Instead of having secondary characters drone on about the dangers of Black, Cuaron utilizes the moving photographs in the newspapers, so the audience never forgets. Because of this, although Oldman, in terms of screen time, is barely in the film, he is a looming presence, just as he is in Harry Potter’s mind. This is the only Harry Potter movie that stands on its own as a good film, the best Harry Potter movie, and it’s not even close.

9. Shaun of the Dead

There are many excellent satires throughout basically every period in cinema. But many of them are not necessarily good movies on their own. That is why Shaun of the Dead is different. You can watch it as a comedy, and it is a hilarious send-up of zombie films. But, importantly and impressively, Shaun of the Dead works on its own as a zombie movie. This is back in the days before we knew what a Cornetto trilogy was, but for my money, this is still the best of the bunch. Obviously, your mileage may vary, but this feels like a labor of love for the stars, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, as well as the director Edgar Wright. It also stands out from most satires as it absolutely holds up on rewatch. The level of detail in both the script and the special effects stand out, even more the second time through. And although this is a zombie movie to the core, it is also an arrested development coming of age story for Shaun. Intermingled with the laughs, blood, gore, and pretty incredible choreography set to Queen is an arc for our protagonist that makes his eventual heroism believable, which is no small feat in this genre.

8. Vera Drake

This is a movie that I caught up with this year, but boy, was it worth the wait. Ok, so, Imelda Staunton. Honestly, I could just end the write up right there. This is one of the best single performances in decades. If you aren’t moved by the end of the film, I think you just might be broken. You can argue that some of the first half-hour is either unnecessary or drags, but you could make that claim of many Mike Leigh films. But more than anything, Vera Drake builds on increasing dread. There is very little hope of a happy ending here. But Leigh’s choice to surround this feeling of closing in with standard family drama allows us to clench even harder, just waiting for the hammer to fall. And when it falls, mainly when the police show up at the family home, our hearts sink. Much of this is due to Staunton’s performance, and sometimes her character’s borderline inability to speak. Everything you need to know about her character is shown through her tremulous speech and the terror in her eyes. But at the same time, Leigh never makes the police out to be villains. The system possibly, but not those sent to enforce it. They are just frustrated workers attempting to do their jobs. Leigh tackles abortion is probably the most even-handed way possible, but making Vera, the main character shifts the film a bit to the left.

7. Somersault

If there is an underseen gem on the list, Somersault is the one. Director Cate Shortland presents us with a carefully crafted story that strikes deeply at the feelings of isolation and vulnerability. Abbie Cornish, in the lead role of Heidi, has never been better before or since 2004. She embodies an imperfect character in ways that are surprising and enlightening. Her numerous friendships and romantic encounters all feel quite real, even when they are clearly mistakes to us on the outside. If this role was performed poorly, she would be an easy character to write off because of her mistakes. But it is that very vulnerability that connects us to her story. The end of the film is a challenging one. Like life, it is not black and white. Should we hope for reconciliation? Or is this another mistake waiting to happen? Shortland does not tell us which is the right decision. Heidi and her mother may turn a page and have a healthy relationship. Heidi and her mother may reenact this pattern yet again, bending until they snap under pressure. But that is the mark of great films, right? These characters have lived before the opening credits, and they will live past the fade to black. Where they go is up to them.

6. Before Sunset

Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke return nine years later. I remember wondering if this could possibly work again. After all, Before Sunrise felt like lightning in a bottle. A walk and talk, 2-hour romance? That’s hard to make work once, but twice? Looking back, it seems silly, because they managed to make this work three times! Regardless of which is your favorite of the trilogy, Before Sunset probably has the most memorable line. “Baby, you are gonna miss that train,” is filled with more sexual and romantic energy than most films could ever hope for in their entire runtime. But it is the build that makes that work. Without the young love of Before Sunrise, without the mistakes they made, without the distance of nine years in between, it is an empty (if still fun) line and moment. But when you add all these up, that is a moment in which you completely understand everything about this, too, even before he responds, “I know.” Before Sunset takes the idyllic romance of Before Sunrise and tests it. They’re no longer young, free, and disconnected. Jesse and Celine have lives, experiences, trials, and tribulations to share. It is a movie of choice points. There are any number of times where they could leave each other’s sights (again), but this time for good. But they don’t, and the audience is treated to love at first sight a second time.

5. La Mala Educaccion (Bad Education)

Known as Bad Education here in the United States, this is yet another work of near-genius from Pedro Almodovar. It earned an NC-17 rating in the United States for depictions of gay oral sex, but that is one of the least interesting parts of the movie. As in many of his films, Almodovar uses the film within a film framing device to not only tell a story but also to provide insight into his characters. Additionally, La Mala Educacion feels like a love letter to cinema and its power to transform. This transformation happens figuratively on the screen, but it also a literal examination of the character Juan/Angel Andrade/Zahara (Gael Garcia Bernal). Bernal has had an incredible career, but this may very well be his best work. Almodovar pulls a sensuality from Bernal that usually lies untapped or hidden beneath the surface. La Mala Educaccion attempts to tackle plenty of themes and critical issues (including molestation of young boys by Catholic priests, hard drug use, and the transgender experience). Given that it was made almost 20 years ago, some moments may rankle us in 2020. But despite that, La Mala Educacion is a tremendous film that ranks high not only in 2004 but in Almodovar’s filmography.

4. Birth

This movie is messed up. You will either love it or hate it. There is zero middle ground or a gray area. After all, in this film, Nicole Kidman is convinced that her dead husband is living in the body of a 10-year-old boy. And things get…awkward. But as far as I’m concerned, director Jonathan Glazer has yet to make a bad film, and obviously Birth is no exception. This is one of my favorite Kidman performances, as well, because she’s clearly aware of how borderline comically bizarre the role is, yet she dives headfirst. Most of the publicity around Birth is due to the scene in the bathtub with Kidman and young co-star Cameron Bright, but frankly, that scene is completely tame. What is interesting is that Glazer has managed to make a film feel both uncomfortable and almost romantic. This is an examination of two things, both quite important. One is the idea that pure romantic love is eternal, or we believe it should be. The other is taking a close look at what happens when that romantic partner is ripped from our lives, sometimes in unexpected ways. What do we do? How do we function after that is taken from us? The thing we are taught that will comfort us as we grow old. How can we possibly recover from that undamaged?

3. Collateral

Look, I know that this is expected of a male reviewer, but I genuinely think that Michael Mann makes the coolest movies imaginable. Even when his films aren’t quite up to his usual level (I’m looking at you, Miami Vice), his aesthetic choices still make them worth watching. When you have stars like Tom Cruise and Jamie Foxx buying in and playing slightly against type and expectation, combined with Mann behind the camera, it almost has to be great. Mann smartly casts the huge star (Cruise) in the supporting role, but gives him many of the best trailer moments. Say what you will about anything else, but that nightclub shootout is about as good as it gets. The enclosed space, the lighting, the choreographed action, it all combines for a scene that will go down as one of Mann’s best. And that’s saying something; the man knows how to integrate action into his films. But really, Foxx is the heart of Collateral. Without him, it would just become 2 hours of “hey, wasn’t that cool.” Foxx’s ability to play the everyman and convince you that, as cool as Tom Cruise is here, he is not who you should be rooting for. This may not be Mann’s best (that probably goes to Heat or The Insider), but it is undoubtedly one of the best of 2004.

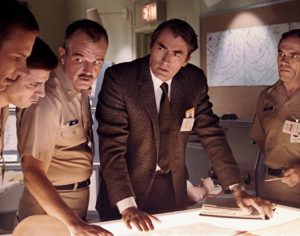

2. The Aviator

Did you think you would get a list out of me, and I wouldn’t include Marty? The Aviator may be Scorsese’s biggest picture, in terms of scale. Even he couldn’t encapsulate all of Howard Hughes’s life in one film, but he does manage to paint a picture of Hollywood through several decades. His decision to use different film techniques that match with the time shows how great of a director Scorsese is, and it shows that he has been given the opportunities to do so. Does he go a little bit overboard with the casting? Sure. Gwen Stefani and Kate Beckinsale stand out as not quite ready for the big time here. But all of that is forgiven because of two things. Well, many things, but we’ll stick to two for this short write up. First, the airplane crash sequence. These harrowing few minutes are incredible to watch on a big screen, but certainly, hold up at home. We know, as the audience, that Hughes will survive, but for the life of me, when I watch it, I can’t imagine how. And of course, there is the casting of Howard Hughes and Katharine Hepburn.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Cate Blanchett respectively light up the screen when they are together. Arguably, Blanchett has the more difficult part. She not only has to do a recognizable voice but has to make her impact immediately due to reduced screen time. If she fails, when she comes to knock on his door after he has begun to succumb to his disorder, we would wonder why he would listen. For once, The Academy got it right, and Blanchett correctly was awarded for Best Supporting Actress. Frankly, this is a film so grand that I could spend another thousand words detailing all the great things about it. But The Aviator is genuinely phenomenal and should be remembered as one of the greatest odes to old Hollywood on record.

1. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

And now we come to it, the best movie of 2004. More than any of the films on this list (or ones that I left off), this is the one that always sticks in my mind. And yes, I see the irony. From a screenplay by Charlie Kaufman, it manages to capture both the giddiness and torture of love and love lost. Despite the science-fiction lens, Eternal Sunshine is remarkable in its reality. The feeling of finding someone who “gets you” is both freeing and terrifying. And the pain of endings is palpable. We have all felt it. We have all wanted desperately to forget, but we should never forget. Just because those feelings have changed does not make them any less real. Both Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet are perfect here, and, if anything, Carrey is undervalued. Obviously, he is well known for his comedic prowess (and for a good reason), but this is, without a doubt, his best performance. It is not merely raw and vulnerable for Jim Carrey. It is the portrait of a wounded human being that anyone who has been heartbroken will feel to our core. Director Michel Gondry’s whimsical style and the choice to tell a non-linear story are utter strokes of genius. Because of this, we can see the anger and cutting betrayal of loss, only to have the beauty of romance revealed to us over the runtime. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is one of the purest examinations of love, and it never pulls any punches. It reveals as much about the audience as it does about its own characters, and that is what makes it the best film of 2004.

Those are the Top 10, but here are some movies I think you should check out. They’re not 11-20, just some films that you should check out totally blind. Some better than others, but they are all…memorable.

-Primer

-Layer Cake

-Kinsey

-Manchurian candidate

-Closer

-Man on Fire

-Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

-The Machinist

-Bride and Prejudice

-Secret Window