Director: RaMell Ross

Writers: RaMell Ross, Joslyn Barnes

Stars: Ethan Herisse, Brandon Wilson, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, Hamish Linklater, Fred Hechinger, Daveed Diggs

Synopsis: Elwood Curtis’ college dreams are shattered when he’s sentenced to Nickel Academy, a brutal reformatory in the Jim Crow South. Clinging to his optimistic worldview, Elwood strikes up a friendship with Turner, a fellow Black teen who dispenses fundamental tips for survival.

In a 1996 interview with Charlie Rose, the late, great critic Roger Ebert gave what is, for my money, the foremost quote about the cinematic experience. When Rose asked why Ebert believed “no other artform touches life the way movies do,” he replied, “It takes us inside the lives of other people. When a movie is really working, we have an out-of-body experience.” Rose laughed: “You’ve seen too many movies, Roger.” Standing his ground, Ebert countered, challenging his interviewer to recall a time where he found himself so wrapped up in the story unfolding on screen that he wasn’t aware of his surroundings, let alone where his car was parked or what was going to happen the next day. “You only care about what’s going to happen to those people next. When that happens, it gives us an empathy for other people who are there on the screen that is more sharp and more affective and powerful than any other artform.”

In the years since the COVID-19 pandemic vacated movie theaters for an extended period and influenced studios to explore the streaming landscape en masse, that sensation has been increasingly rare. Anomalies existed in certain cases, of course. I can specifically recall the various feelings that washed over me when I watched films like Top Gun: Maverick, Nope, TÁR, Bones and All, and Aftersun, all in 2022. And while the out-of-body viewing experiences returned to a semi-regular state in 2023, the film year was dominated by two titles, and neither Oppenheimer nor Barbie really had that “you only care about what’s going to happen to those people next” quality that Ebert described. Christopher Nolan’s masterpiece is a biopic; even if you lacked a passing knowledge on J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life, you understood that the film about his life’s work and the consequences that followed his world-altering invention was rooted in truth, its outcomes thus predetermined. Greta Gerwig’s Barbie was, well, a movie about Barbie(s), as well as an exploration of identity and gender roles in modern society. When Margot Robbie’s Barbie tells a doctor’s office receptionist “I’m here to see my gynecologist!” at the end of the film, we aren’t exactly left wondering how that appointment went as we wander aimlessly into the parking lot, clicking the lock button on our keys in an effort to set off a “beep” that sends us in the proper direction of our vehicle.

On the other hand, RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys feels like – and, in many ways, is – a revelation, not solely because of the technical command that lies within, and not evenstrictly due to the magnetic turns from its breakout star duo and the established supporting players that surround them. Adapted from Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name, Ross’ film is uniquely-striking in just how potent and formidable it is, both as a feat of storytelling and as a triumph in emotional hijacking. It sounds dramatic, but to say that my facilities were rendered useless while watching it open this year’s New York Film Festival is not a hyperbolic way to describe the circumstances of my first viewing of the film. In fact, it may not be intense enough.

Indeed, I am certain that I was out-of-body while watching Nickel Boys, both on the festival’s first official day and its last, yet what might be an even stronger plaudit is the fact that my knowledge of the film’s events – both from having seen it once already and from having read Whitehead’s novel years ago – did not remotely hinder the viewing experience. It couldn’t have, even if it actively tried: The film is so sensitive and immense; it is wholly indicative of having a visionary talent at its helm. No amount of plot awareness could possibly take away from the judicious emotional onslaught it offers. Much like Ross’ prior film, the Oscar-nominated Hale County This Morning, This Evening, its artistic ambitions are features, not bugs or gimmicks, no matter how many short-sighted viewers wish to reduce them to such empty terms.

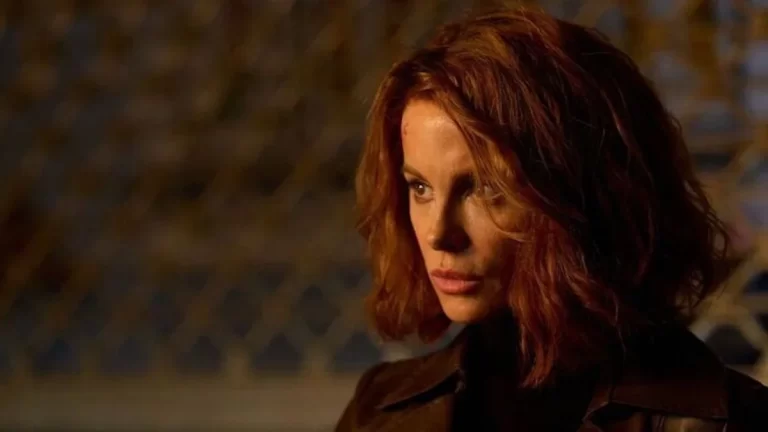

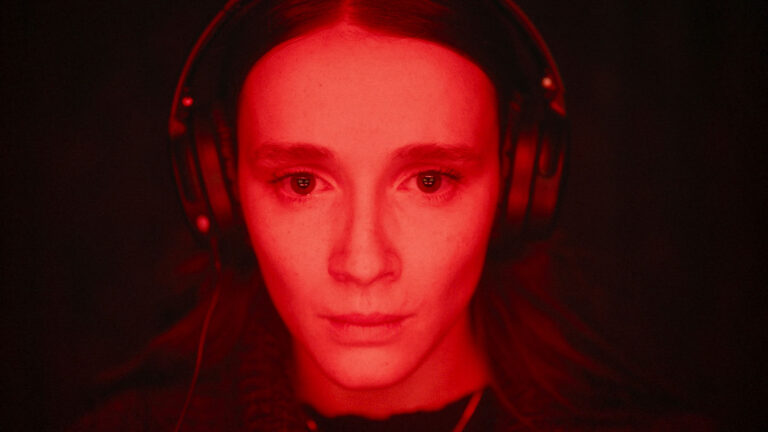

Of course, Ross didn’t craft Nickel Boys with such praise as an objective. That he and his film deserve it are a natural byproduct of its mastery, both in terms of craftsmanship and narrative prowess. The proceedings entirely take place in Jim Crow-era Florida, beginning with Elwood Curtis (played as a child by Ethan Cole Sharp and as a teen by Ethan Herisse) coming of age in two separate life stages. During his youth, we only see Elwood in reflections – in an iron moving back and forth across an ironing board as his “Nana” (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) steams a bedsheet; in a store window displaying an array of television sets, all of which are broadcasting Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “How Long, Not Long” speech, which he gave in Montgomery, Alabama on March 25, 1965 immediately following the Selma-to-Montgomery March he led. As he matures, he comes into clearer view, though still only in reflections for a time, as Ross’ film is shot entirely from a point-of-view perspective. Cinematographer Jomo Fray (All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt) places his camera in lock-step with the two main character’s eyelines and head movements, only ever breaking that gaze in favor of retreating behind their shoulders, as it primarily does with one character (portrayed by the back of Daveed Diggs’ head) later in the picture.

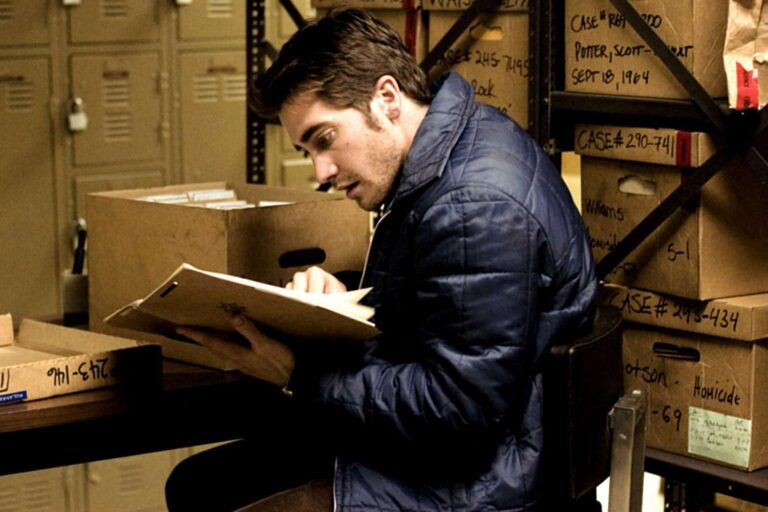

His name is Turner (Brandon Wilson, giving the finest performance in a film full of them); he and Elwood meet a few days after the latter arrives at Nickel Academy, a facility dubbed a “reform school.” Though Elwood, a standout student, was supposed to begin taking advanced courses at Melvin Griggs Technical School – “Imagine a textbook with nothing to cross out,” Mr. Hill (Jimmie Fails), Elwood’s high school teacher, tells him – he never made it there. Despite Nana’s pleas that “he just got into the wrong car,” having hitched an unfortunate ride with a smooth-talking, well-dressed Black man that police accuse of stealing the car he drives. Simply put, a young Black man in the Deep South during the 1960s was implicated if present, actual guilt was of no consequence.

Elwood’s “behavior” requires rehabilitation, something he hopes to be a smooth process considering how mild-mannered Nickel looks as he makes his way down its driveway while sitting in the back of a squad car, his second such situation in a matter of days. If only he was allowed to exit the car with his fellow passengers, both young White men, who might as well be going to an entirely different establishment than Elwood’s future home. This, of course, is the more menacing side of Nickel, the one domineered by the vacant, soulless Mr. Spencer (Hamish Linklater), a cruel White man who continuously warns the boys of “a place” for those who misbehave, somewhere they won’t like. He’ll “see to it personally.”

Turner, who is introduced in one of the single best cinematic moments I’ve seen in many years, becomes something of a saving grace for Elwood’s sanity, insofar as that is possible in a place this vacuously cruel. We learn this the moment Elwood arrives. Ross, when not cutting to the opening scene from The Defiant Ones, featuring the voice of Sidney Poitier singing “Long Gone,” deploys the harshest, most ominous notes from Scott Alario and Alex Somers’ score. These notes, featuring sharp violin strums and the light taps of a drumstick against what sounds like a hollow pipe, evoking the sound of a strike against a jail cell’s bar.

The juxtaposition between the darkness this sequence is imbued with and the early scenes in which a seemingly-joyful Elwood spends time lying beneath the Christmas tree as his grandmother lets tinsel fall towards his body, or when he triumphantly joins a protest of a local screening of The Ugly American, show the brilliant cognizance employed by Ross in knowing that Elwood can both be raced and have faith in the country’s potential to be better, more accepting.

The way that Ross, the film’s co-writer, Joslyn Barnes, and Fray capture the similarities and differences between their two main characters are subtle yet distinct, and beautifully so. Ross has mentioned previously that he was curious while reading the source material about when Elwood was raced, and in the film, we see him repeatedly looking down at his fingertips, his forearms, even his grandmother’s knee in the bathtub; there was certainly a time in Turner’s life when he realized he was raced, but we don’t see it occur, as if it was so long ago in Turner’s somewhat jilted existence that he views it as having always been the case. While enjoying the solace of their dorm’s sparse rec room, Elwood journals and writes letters to Nana, while Turner scours the instructions on old toy pamphlets; when the boys sneak off to hide from the trials of the day in a storage shed, Elwood reads “Pride & Prejudice” as Turner listens to a ball game. The most concrete difference between the two lies in how Elwood’s naivety to society’s treatment of young men like him is, in a sense, disguised as optimism. He wonders aloud, “How can they do that?” when a note from his grandmother tells him that Nickel’s staff wouldn’t let her see him because he was “sick,” a falsity, not realizing that the answer to his rhetorical question is as simple as “because they can.” Turner, meanwhile, is fully aware that the only way someone like him can leave Nickel is to run. Still, they share kindred dreams for the future, one that features them both, free men in a world that leaves them be. Would that it were so simple.

As fascinating, gutting, and brilliant as Nickel Boys is, the same could be said for the experience that is watching (or reading) Ross talk about his film, as I was able to do twice at this year’s New York Film Festival. The first time came at a post-screening press conference on the fest’s first day, and the second during a discussion between him and Barry Jenkins. Besides being as much of an intellectual treat as it sounds, their exchange was full of further insight into how Ross came to adapt Whitehead’s novel. He has spoken at length in multiple interviews on when he realized the film needed to be seen from a “sentient perspective,” as it was called on-set – “Immediately,” is the short answer, – but what is even more fascinating about Nickel Boys’ construction is how the director and his crew gained a better understanding of who Elwood and Turner were as human beings beyond the page. As Ross described it, “The primary exercise in writing the film [was] using adjacent images… images that are one step removed from literal narrative thrust.” Ross went on to share that he believes “cinema skipped photography… when you make a [single] image, that’s it. It’s done. When you make a film, you’re sacrificing the singularity of the image for narrative length.” That process, in his eyes, sees a filmmaker going about things like, “This will do, because this will get us here, and it’s about getting here.” Ross balks at that. Instead, he wants his script and the images created from the words he and Barnes wrote to serve “the human process of being a poetic looker.”

In and of itself, that’s both a beautiful way to put things and a beautiful idea at its core. But it represents something about Ross’ filmmaking sensibilities that transcends ability entirely, something that is more intrinsically linked to his humanity than his talent. Nickel Boys is many things, but above all, it is an immense statement about love. About how it can be communicated through photography, both when fixed and in motion, and how that should inherently be the pulse that propels a work of art forward, just as it does this film, perhaps more than any work of art in recent memory.

While wrapping up their talk, Jenkins brought up his debut, 2008’s superb Medicine for Melancholy, a film that, fittingly, is as romantic a movie as was released during the 2000s. In noting how its festival run afforded him the opportunity to see the world, Jenkins told a story that dinner guests everywhere would salivate over if afforded the opportunity to bear witness: It was the day after Barack Obama was elected president, and ironically, Jenkins found himself at a dinner full of “these very hoity-toity Argentine intellectuals” who asked him, “What has the U.S. ever given to the world?” One guest answered for him: “Your people, they made jazz.” Another person chimed in: “The instruments, they weren’t for you until they were. And once they were, this whole new sound came out of them.” Jenkins then turned to address Ross directly, saying, “When I shout you out… it’s because the tools are now in your hands. And different sounds, different images come out of them.” If Nickel Boys is any indication – and it undoubtedly seems to be –these tools have never been in a better pair of hands.

Nickel Boys opened the 62nd New York Film Festival and will be released in theaters by Amazon MGM Studios on December 13.

Grade: A+