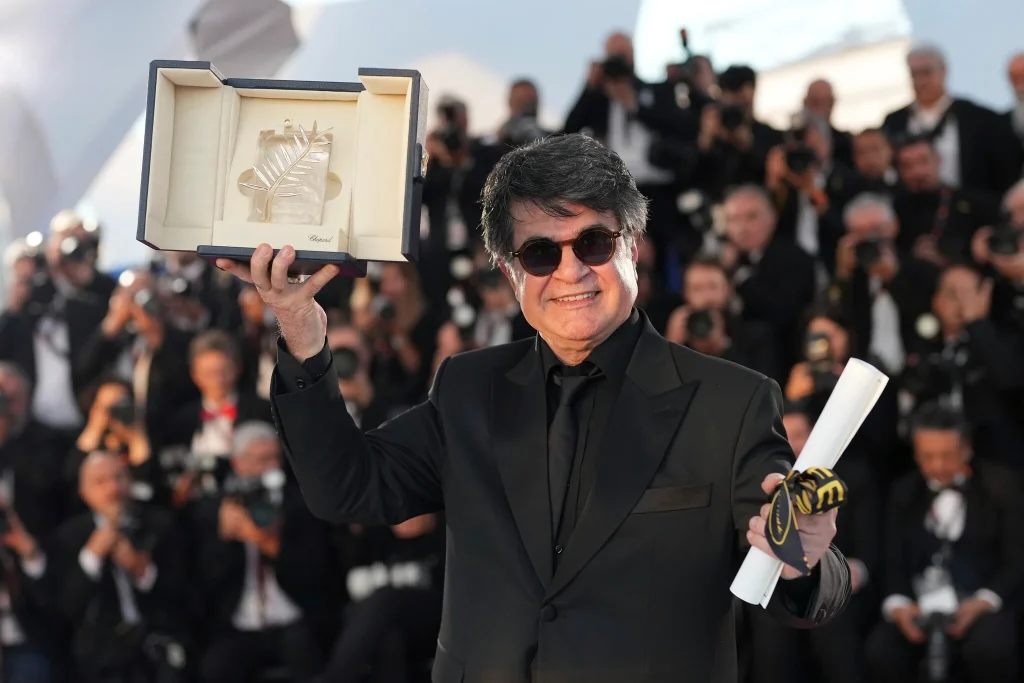

With the Palme d’Or win for his latest movie, It Was Just An Accident, Iranian director Jafar Panahi joins an elite class of directors who’ve won the big three festival prizes at Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. Frenchman Henri-Georges Clouzot, Italian Michelangelo Antonioni, and American Robert Altman all won the Palme d’Or, Golden Lion, and Golden Bear as well, and they are legends in their own right. Panahi may not be a major standout from Iran compared to Asghar Farhadi and Abbas Kiarostami, but Panahi has been in the business long enough that his name now has to be considered among the elites from the notoriously censorious nation. Winning the Palme d’Or is probably the best middle finger Panahi could give to the authorities at home, who have banned him from filmmaking, yet he continues to defy.

Panahi’s filmmaking experience came from his days in the military when he was conscripted into the army during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. He was their cinematographer, capturing footage on the ground as part of the propaganda for the newly established Islamic Republic, and was a Prisoner of War for 76 days. After his discharge, Panahi enrolled in film school, where his exposure to Western films influenced his style going into narrative filmmaking during the ’90s. After a series of short documentaries and serving as Kiarostami’s assistant for his film, Through the Olive Trees, Panahi made his narrative feature debut in 1995 with The White Balloon.

The film follows a young girl who wants to buy a goldfish but is unable due to her mother’s refusal to give her the money. She tries to trick her way into getting the money, but manages to lose it twice and tries to get it back. Worldwide acclaim for The White Balloon won numerous awards for Panahi and was submitted by Iran as the country’s nominee for Best International Film at the Oscars. However, the government attempted to withdraw the nomination, which was refused; this would start a series of interferences between the government and Panahi. In 2000, Panahi released The Circle, winning the Golden Lion at Venice. The drama, which was critical of Iran’s treatment of women, was later banned by the authorities, and so was his next feature, Crimson Gold.

Iran’s strict rules on what can be depicted about Iranian society, as well as formal permission from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, have always clamped down on certain dissents made by artists. His next film, Offside, was even a more direct attack on the government, the story about a group of girls who disguise themselves as boys to watch a soccer game. Iran prohibits women and girls from attending certain sporting events to prevent women from hearing crude language and seeing men in shorts and t-shirts; again, Panahi refused to change the story and filmed in secret. He was able to set up outside distribution and sneak the film out of Iran before the authorities banned and confiscated it. By then, authorities moved to crush open dissent harder after the Green Movement in 2009, which Panahi supported, and he was arrested.

Along with fellow director Mohammad Rasoulof, Panahi was convicted of “intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic,” and sentenced to six years imprisonment plus a twenty-year ban from any work in media. The international response was massive, with many organizations, filmmakers, actors, and other public figures condemning the sentences. Panahi was later allowed to serve his sentence under house arrest, where he continued to make movies in secret. This Is Not A Film follows him over ten days, talking to his lawyers while appealing his sentence and reflecting on his career up to then. Closed Curtain was filmed secretly at his home about two people in hiding from the police – a docufiction mirroring Panahi’s situation. In 2015, Taxi, which won Panahi the Golden Bear in Berlin, follows the director while working as a cab driver, talking to his passengers about daily life in Tehran, who speak openly about how they feel about what is happening in their country.

By the time he made It Was Just An Accident, also shot secretly and without permission due to his filmmaking ban, Panahi was officially free and allowed to travel out of the country. At the Cannes Film Festival for the first time in years, Panahi presents a story about how a man who accidentally runs over a dog snowballs into a much serious conflict that challenges all the characters involved. Again, it challenges Iranian authority with women being shown not wearing their hijab, a law Iranian officials have taken a hardline stance on. Panahi gave tribute to other artists at home who remain banned from working or travelling, and his victory at Cannes solidifies Panahi as one of the most important filmmakers in the world. Neon has the rights to the film, which means it’s an immediate Oscar contender later in the year.

Iran is a country that has produced an incredible wealth of amazing movies, but is also challenged by theocratic rule, which demands obedience and following of Islamic law. Many Iranian artists have now gone on to live in exile so they can openly criticize the government and demand change. Panahi, however, has refused to go into exile, continuing to make movies in his homeland in defiance of the law. “Those who are making their first films are forced to do whatever they are told; they allow the censors to mutilate their films,” said Panahi in an interview. “If we do not stand up to the censors, the conditions will be worse for the young filmmakers.” His daring storytelling makes him a hero to everyone who stands for freedom of expression and the refusal to compromise against a restrictive machine.

Follow me on BluSky: @briansusbielles.bsky.social

![The Shining (1980) [REVIEW] | The Wolfman Cometh](https://thewolfmancometh.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/the-shining-movie-jack-nicholson-jack-torrance-laughing.jpg)