Director: Tracie Laymon

Writer: Tracie Laymon

Stars: Barbie Ferreira, John Leguizamo, French Stewart

Synopsis: When lonely 20-something Lily Trevino accidentally befriends a stranger online who shares the same name as her own self-centered father, encouragement and support from this new Bob Trevino could change her life.

The simple kindness of another human being is something we could all use. An acknowledgement of our existence or a bit of encouragement is fulfilling. It can be hard to be lonely and to not know how to tone down the excitement you, as a lonely person, feel because of a simple interaction. It can be hard when you’re desperate for that modicum of human kindness because the people who are supposed to do it unconditionally and don’t are the cruelest of all.

Bob Trevino Likes It isn’t reinventing the idea of found family, but reinforcing why it is the most important thing we can do for one another. To choose to love someone is to show them that they are known. While most of us haven’t experienced the utterly reprehensible self-centeredness of Lily’s (Barbie Ferreira) father Bob Trevino (French Stewart), we still feel that a biological link isn’t the strongest link there is even with the worst of our biological family shouting at us how important that link is.

Writer and director Tracie Laymon has brought a story to life that will open up a lot of wounds, but only to allow the idea that they can heal properly. The story is based on Laymon’s own experiences and she brings a depth to it that really opens Bob Trevino Likes It to a wholly new take on a strained parent/child relationship. She writes each character with such a loving eye. All of them are broken, but with each other can be rebuilt.

There aren’t any easy answers, either. There are difficult conversations, things left unsaid, and misinterpretations of actions. There’s a scene with Lily and her new friend Bob Trevino (John Leguizamo) that really emphasizes this shift in perception. The two of them are having a nice, if a little stiff, conversation when Lily takes a call from the woman she works for, Daphne (Lauren “Lolo” Spencer), who accidentally mentions Lily’s lie that this Bob is her father. Bob is notably upset and, as a defense mechanism, Lily tries to do everything she did to appease her father when he got upset, but none of it works. She then tries to walk away. Bob stops her and says that they need to talk about it. He’s telling her in a way he wants to try and work out why Lily lied and get past it.

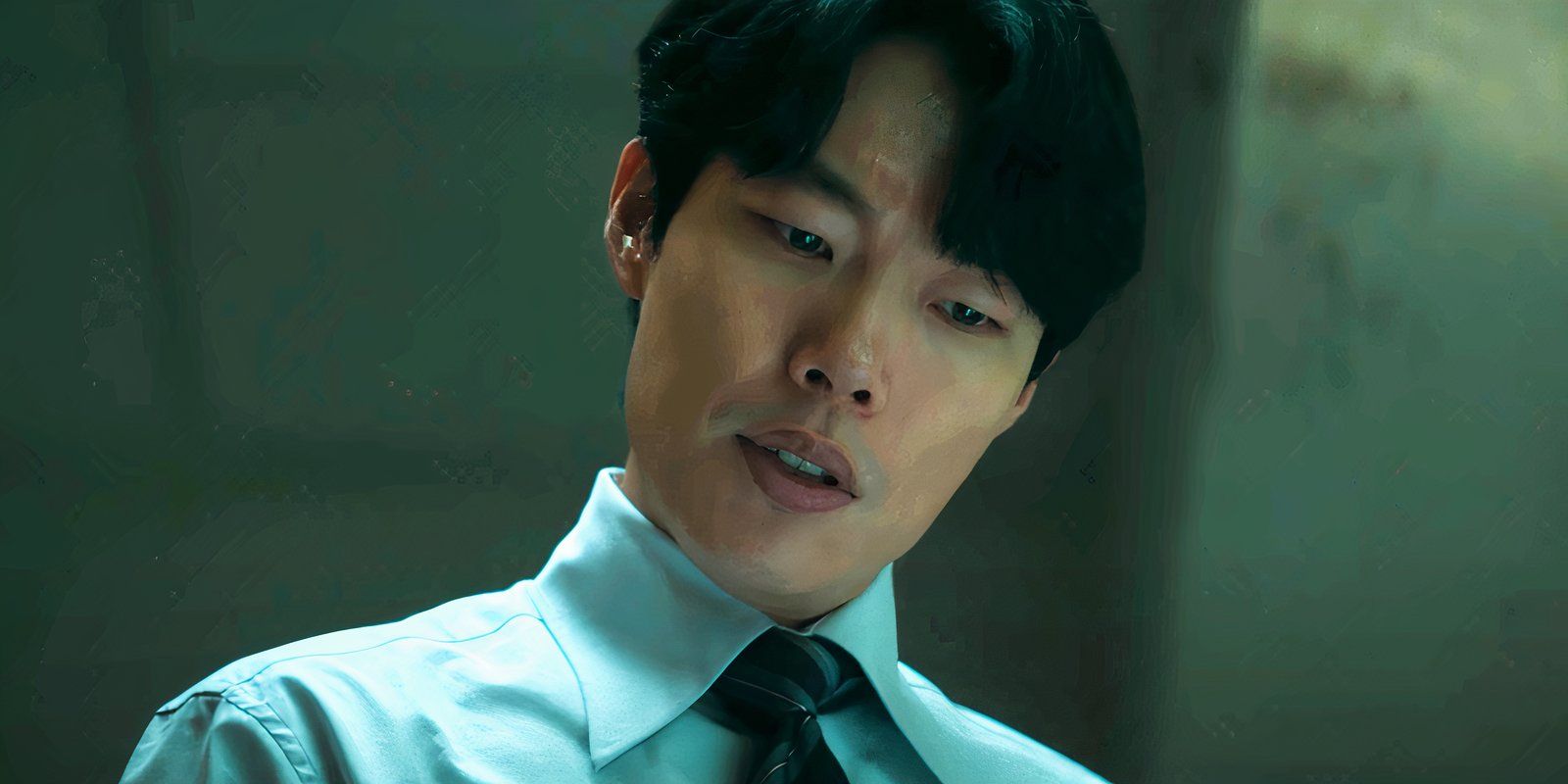

This is where Laymon’s great work as a director matches her phenomenal script. Instead of shooting Bob as he calms Lily down, Laymon and cinematographer John Rosario focus on Lily’s face. We watch as Lily realizes Bob is making an effort. Her face gets softer and her mouth opens a little. It’s a perfect turning point in this character’s life. It’s like a light bulb has been illuminated. Laymon and Rosario then continue this movement as we watch from outside as Lily and Bob talk, really talk. The shot of the two of them through the diner window, the silence of the dialogue, and the musical cue is just beautifully composed.

Bob Trevino Likes It is not only blessed with behind-the-scenes talent, but the actors are superb as well. While French Stewart gives a villainous performance for the ages, the two leads are utterly magnetic together. Barbie Ferreira is an actress who is incredibly adept at character work. Her physicality and presence make her a chameleon. As Lily, she breaks your heart and then mends it so that you laugh through your copious tears. John Leguizamo proves once again he’s an incredibly talented actor, if given the right material. He plays mundane in a way that’s incredibly compelling to watch. The two of them together are the perfect combination. Their chemistry is dynamite even as they have those awkward first steps that all new friendships go through.

Bob Trevino Likes It is a film that reminds us of the capabilities we all have to be better humans to each other. You don’t have to go as far as Bob, but meeting someone where they’re at is a good first step. A hello, a small conversation, or an acknowledgement of their being is sometimes enough. It’s enough to give that person the strength and knowledge that they are seen. That’s a beautiful thing and Bob Trevino Likes It is an absolutely beautiful film.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Bill-Skarsgard-Locked-012925-c94b9b41775a4b7996beb5328ede1981.jpg)