This week on the InSession Film Podcast, we featured our 11th annual InSession Film Awards! During Part 1, we discussed the very best that 2023 had to offer in terms of film. We dove into everything from movie surprises, to overlooked movies, to the best acting performances and so much more!

For every category, we each listed our own nominations and winners. Winners are highlighted in bold.

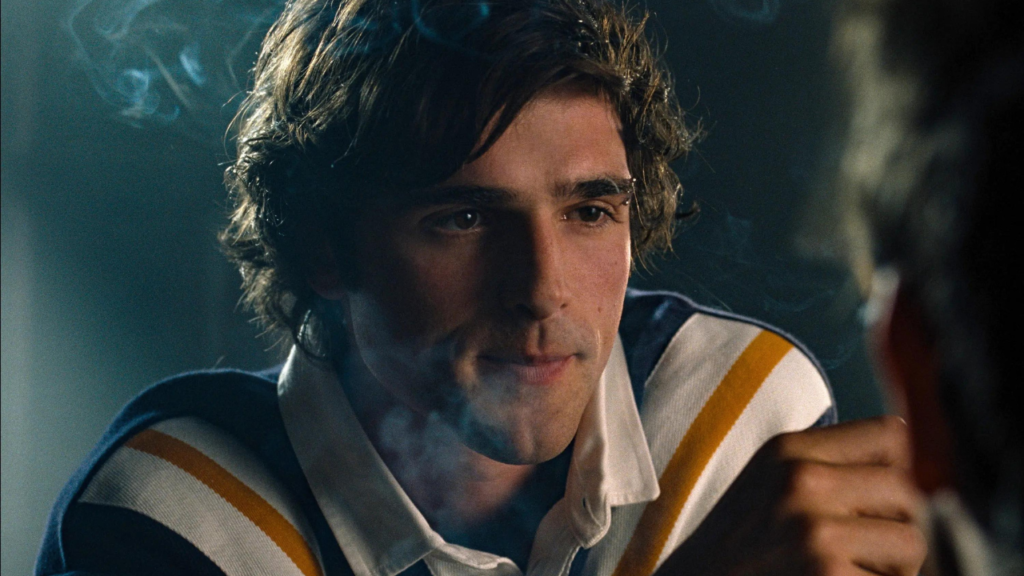

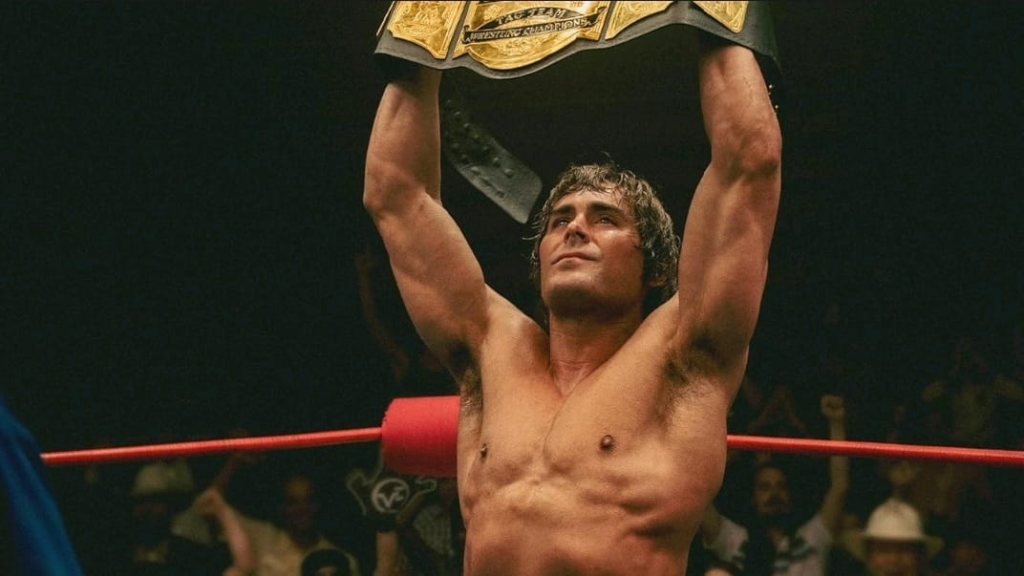

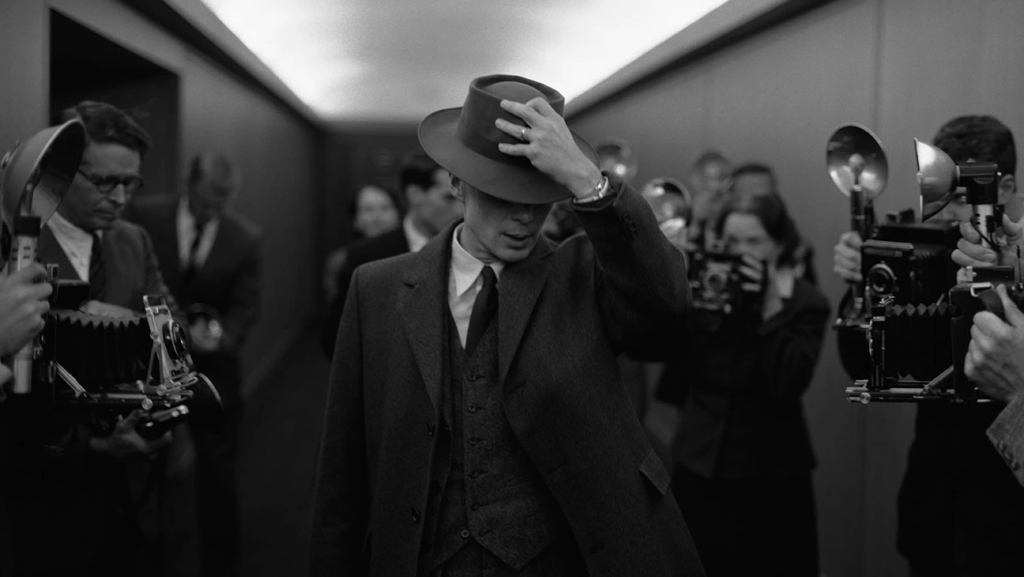

Best Actor

Brendan:

- Zac Efron, The Iron Claw

- Paul Giamatti, The Holdovers

- Koji Yakusho, Perfect Days

- Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer

- Teo Yoo, Past Lives

JD:

- Jeffrey Wright, American Fiction

- Paul Giamatti, The Holdovers

- Cillian Murphey, Oppenheimer

- Andrew Scott, All of Us Strangers

- Koji Yakusho, Perfect Days

Jay:

- Zac Efron, The Iron Claw

- Jamie Foxx, The Burial

- Paul Giamatti, The Holdovers

- Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer

- Andrew Scott, All of Us Strangers

Ryan:

- Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer

- Andrew Scott, All of Us Strangers

- Christian Friedel, The Zone of Interest

- Michael Fassbender, The Killer

- Franz Rogowski, Passages

Best Actress

Brendan:

- Greta Lee, Past Lives

- Natalie Portman, May December

- Alma Pöysti, Fallen Leaves

- Margot Robbie, Barbie

- Cailee Spaeny, Priscilla

JD:

- Cailee Spaeny, Priscilla

- Sandra Hüller, Anatomy of a Fall

- Greta Lee, Past Lives

- Natalie Portman, May December

- Emma Stone, Poor Things

Jay:

- Jennifer Lawrence, No Hard Feelings

- Greta Lee, Past Lives

- Margot Robbie, Barbie

- Emma Stone, Poor Things

- Cailee Spaeny, Priscilla

Ryan:

- Greta Lee, Past Lives

- Carey Mulligan, Maestro

- Cailee Spaeny, Priscilla

- Aunjunue Ellis-Taylor, Origin

- Natalie Portman, May December

Best Actor Supporting Role

Brendan:

- Jamie Bell, All of Us Strangers

- Milo Machado-Graner, Anatomy of a Fall

- Holt McCallany, The Iron Claw

- Charles Melton, May December

- Dominic Sessa, The Holdovers

JD:

- Charles Melton, May December

- Jamie Bell, All of Us Strangers

- Ben Whishaw, Passages

- Milo Machado-Graner, Anatomy of a Fall

- Ryan Gosling, Barbie

Jay:

- Robert Downey Jr., Oppenheimer

- Ryan Gosling, Barbie

- Holt McCallany, The Iron Claw

- Charles Melton, May December

- Chris Messina, Air

Ryan:

- Charles Melton, May December

- John Magaro, Past Lives

- Robert De Niro, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Ben Whishaw, Passages

- Donnie Yen, John Wick: Chapter 4

Best Actress Supporting Role

Brendan:

- Juliette Binoche, The Taste of Things

- Sandra Hüller, The Zone of Interest

- Penélope Cruz, Ferrari

- Da’Vine Joy Randolph, The Holdovers

- Rachel McAdams, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

JD:

- Danielle Brooks, The Color Purple

- Da’Vine Joy Randolph, The Holdovers

- Penélope Cruz, Ferrari

- Juliette Binoche, The Taste of Things

- Rachel McAdams, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Jay:

- Penélope Cruz, Ferrari

- Hong Chau, Showing Up

- Minami Hamabe, Godzilla Minus One

- Da’Vine Joy Randolph, The Holdovers

- Rachel McAdams, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Ryan:

- Rachel McAdams, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Sandra Hüller, The Zone of Interest

- Rachel McAdams, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Paula Beer, Afire

- Julianne Moore, May December

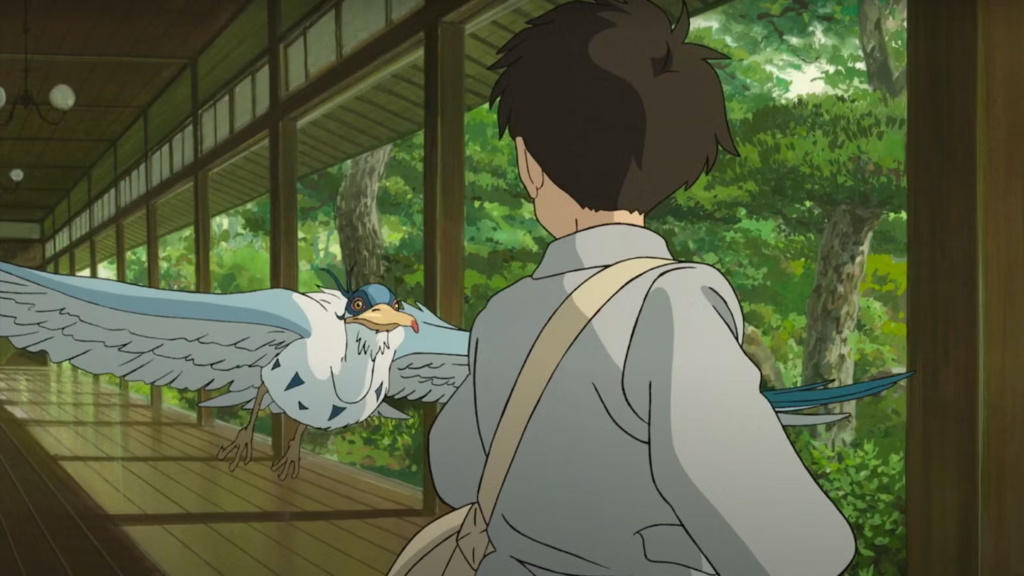

Best Director

Brendan:

- Todd Haynes, May December

- Hayao Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Aki Kaurismäki, Fallen Leaves

- Wim Wenders, Perfect Days

JD:

- Wes Anderson, Asteroid City

- Jonathan Glazer, The Zone of Interest

- Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Todd Haynes, May December

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

Jay:

- Sean Durkin, The Iron Claw

- David Fincher, The Killer

- Todd Haynes, May December

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

Ryan:

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Todd Haynes, May December

- Jonathan Glazer, The Zone of Interest

- Hayao Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron

Best Original Screenplay

Brendan:

- Nicole Holofcener, You Hurt My Feelings

- Samy Burch, May December

- David Hemingson, The Holdovers

- Justine Triet & Arthur Harari, Anatomy of a Fall

- Samy Burch, May December

JD:

- Wes Anderson, Asteroid City

- Samy Burch, May December

- Celine Song, Past Lives

- Justine Triet & Arthur Harari, Anatomy of a Fall

- David Hemingson, The Holdovers

Jay:

- David Hemingson, The Holdovers

- Nicole Holofcener, You Hurt My Feelings

- Paul Schrader, Master Gardener

- Samy Burch, May December

- Aki Kaurismäki, Fallen Leaves

Ryan:

- Samy Burch, May December

- Wes Anderson, Asteroid City

- Christian Petzold, Afire

- Ira Sachs, Passages

- Celine Song, Past Lives

Best Adapted Screenplay

Brendan:

- Troy Kennedy Martin, Ferrari

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Eric Roth & Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Kelly Fremon Craig, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Andrew Kevin Walker, The Killer

JD:

- Cord Jefferson, American Fiction

- Andrew Haigh, All of Us Strangers

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Eric Roth & Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Sofia Coppola, Priscilla

Jay:

- Sofia Coppola, Priscilla

- Eric Roth & Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Kelly Fremon Craig, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Takashi Yamakazi, Godzilla Minus One

Ryan:

- Ava DuVerney, Origin

- Sofia Coppola, Priscilla

- Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer

- Kelly Fremon Craig, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Andrew Haigh, All of Us Strangers

Best Cinematography

Brendan:

- Ruben Impens, The Eight Mountains

- Dariusz Wolski, Napoleon

- Hoyte van Hoytema, Oppenheimer

- Robert Yeoman, Asteroid City

- Rodrigo Prieto, Killers of the Flower Moon

JD:

- Lukas Zal, The Zone of Interest

- Rodrigo Prieto, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Maria von Hausswolff, Godland

- Hoyte van Hoytema, Oppenheimer

- Robert Yeoman, Asteroid City

Jay:

- Mátyás Erdély, The Iron Claw

- Erik Messerschmidt, The Killer

- Hoyte van Hoytema, Oppenheimer

- Rodrigo Prieto, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Maria von Hausswolff, Godland

Ryan:

- Rodrigo Prieto, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Erik Messerschmidt, Ferrari

- Christopher Blauvelt, May December

- Hoyte van Hoytema, Oppenheimer

- Hans Fromm, Afire

Best Documentary

Brendan:

- 20 Days in Mariupol

- Four Daughters

- Beyond Utopia

JD:

- Kokomo City

- 20 Days in Mariupol

- Beyond Utopia

- Four Daugthers

- The Deepest Breath

Jay:

- Still: A Michael J. Fox Movie

- BS High

Ryan:

- Four Daugters

- Beyond Utopia

- The Pigeon Tunnel

Best International Film

Brendan:

- The Boy and the Heron

- Godzilla Minus One

- Fallen Leaves

- Perfect Days

- The Taste of Things

JD:

- The Zone of Interest

- Anatomy of a Fall

- Past Lives

- Perfect Days

- The Taste of Things

Jay:

- Afire

- The Boy and the Heron

- Fallen Leaves

- Godland

- Godzilla Minus One

Ryan:

- Afire

- Anatomy of a Fall

- The Taste of Things

- Godzilla Minus One

- The Zone of Interest

Best Animated Movie

Brendan:

- Suzume

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Robot Dreams

- The Boy and the Heron

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

JD:

- The Boy and the Heron

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

- Elemental

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Robot Dreams

Jay:

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- The Boy and the Heron

- Robot Dreams

- Nimona

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

Ryan:

- The Boy and the Heron

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Robot Dreams

Best Original Score

Brendan:

- Ludwig Goransson, Oppenheimer

- Joe Hisaishi, The Boy and the Heron

- Christopher Bear & Daniel Rossen, Past Lives

- Daniel Pemberton, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Ryuichi Sakamoto, Monster

JD:

- Jerskin Fendrix, Poor Things

- Mica Levi, The Zone of Interest

- Joe Hisaishi, The Boy and the Heron

- Ludwig Goransson, Oppenheimer

- Daniel Pemberton, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Jay:

- Daniel Pemberton, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Ludwig Goransson, Oppenheimer

- Joe Hisaishi, The Boy and the Heron

- Robbie Robertson, Killers of the Flower Moon

- Marcelo Zarvos, May December

Ryan:

- Ludwig Goransson, Oppenheimer

- Joe Hisaishi, The Boy and the Heron

- Daniel Pemberton, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

- Mica Levi, The Zone of Interest

- Christopher Bear & Daniel Rossen, Past Lives

Best Use of Soundtrack Music (Doesn’t have to be original. Closing and Opening credits count)

Brendan:

- “The Power of Love” by Frankie Goes to Hollywood, All of Us Strangers

- “Tyrone” by Erykah Badu, They Cloned Tyrone

- “Feeling Good” by Nina Simone, Perfect Days

- “Tom Sawyer” by Rush, The Iron Claw

- “September” by Earth Wind & Fire, Robot Dreams

JD:

- “September” by Earth Wind & Fire, Robot Dreams

- “Peaches” by Jack Black, Super Mario Bros

- “Dear Alien” by Asteroid City Cast, Asteroid City

- “Why May I Not Go Out and Climb the Trees” by Daniel Norgren, The Eight Mountains

- “Feeling Good” by Nina Simone, Perfect Days

Jay:

- “1954 Godzilla Theme” by Akira Ifukube, Godzilla Minus One

- The Smiths, The Killer

- “Push” by Matchbox Twenty, Barbie

- “I Will Always Love You” by Dolly Parton, Priscilla

- “Le Monde” by Richard Carter, Talk to Me

Ryan:

- “Live That Way Forever” by Little Scream – The Iron Claw

- “How Soon Is Now” by The Smiths – The Killer

- “Dance The Night” by Dua Lipa – Barbie

- “The Power of Love” By Frankie Goes to Hollywood – All of Us Strangers

- “Last Train to San Fernando” By Johnny Duncan & The Bluegrass Boys – Asteroid City

Best Opening/Closing Credits Sequence or Scene

Brendan:

- Eileen (Opening Credits)

- Evil Dead Rise (Opening Title Reveal)

- Master Gardener (Opening Credits)

- Peter Pan & Wendy (Opening/Closing Credits)

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Opening Credits)

JD:

- Oppenheimer (Closing)

- Past Lives (Closing)

- Perfect Days (Closing)

- The Zone of Interest (Closing)

- Killers of the Flower Moon (Closing)

Jay:

- Killers of the Flower Moon (Closing)

- May December (Closing)

- Past Lives (Closing)

- Barbie (Opening)

- Oppenheimer (Closing)

Ryan:

- Oppenheimer (Closing)

- Killers of the Flower Moon (Closing)

- May December (Closing)

- The Zone of Interest (Closing)

- The Taste of Things (Opening)

Best Overlooked Movie

Brendan:

- The Burial

- You Hurt My Feelings

- Flora And Son

- Showing Up

- The Eight Mountains

JD:

- The Taste of Things

- The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (Dahl Shorts)

- Passages

- Godland

- Showing Up

Jay:

- Master Gardener

- Rye Lane

- The Covenant

- You Hurt My Feelings

- The Burial

Ryan:

- Origin

- All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt

- Afire

- Memory

- The Royal Hotel

Best Surprise Movie

Brendan:

- Bottoms

- The Color Purple

- Godzilla Minus One

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

- Scream VI

JD:

- Wingwomen

- Godzilla Minus One

- Knock at the Cabin

- Fallen Leaves

- Perfect Days

Jay:

- Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

- Godzilla Minus One

- Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Poor Things

- They Cloned Tyrone

Ryan:

- Avatar: The Way of Water

- Cha Cha Real Smooth

- Confess, Fletch

- The Eternal Daughter

- Puss in Boots: The Last Wish

Best Surprise Actor/Actress

Brendan:

- Dave Bautista, Knock at the Cabin

- Bradley Cooper, Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

- Patrick Dempsey, Ferrari

- Marshawn Lynch, Bottoms

- Melissa Barrera, Scream VI

JD:

- Adele Exarchopolous, Wingwomen

- Glen Howerton, Blackberry

- David Krumholtz, Oppenheimer

- Zac Efron, The Iron Claw

- Rupert Friend, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (The Swan)

Jay:

- Charles Melton, May December

- Cailee Spaeny, Priscilla

- Harris Dickinson, The Iron Claw

- Josh Hartnett, Oppenheimer

- Benny Safdie, Oppenheimer / Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Ryan:

- Benny Safdie, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Jacob Elordi, Priscilla

- Claire Foy, All of Us Strangers

- Casey Affleck, Oppenheimer

- Viola Davis, Air

Best Movie Discovery

Brendan:

- Celine Song – Director, Past Lives

- Dominic Sessa – Actor, The Holdovers

- Milo Machado-Graner – Actor, Anatomy of a Fall

- Sherry Cola – Actress, Joy Ride

- Samy Burch – Writer, May December

JD:

- Maria von Hausswolff – Cinematographer, Godland

- Samy Burch – Writer, May December

- Celine Song – Director, Past Lives

- Kyle Edward Ball – Director, Skinamarink

- Ayo Edebri – Actress, Bottoms / Theater Camp / Mutant Mayhem / Spider-Verse

Jay:

- Aki Kaurismäki – Director, Fallen Leaves

- Dominic Sessa – Actor, The Holdovers

- Celine Song – Director, Past Lives

- Raine Allen-Miller – Director, Rye Lane

- Juel Taylor – Director, They Cloned Tyrone

Ryan:

- Dominic Sessa – Actor, The Holdovers

- Samy Burch – Writer, May December

- Celine Song – Director, Past Lives

- Cailee Spaeny – Actress, Priscilla

- Raven Jackson – Director, All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt

JD’s Individual Special Awards

Best Individual Score Track

- “Falling Blocks” – Lorne Balfe (Tetris)

- “Falling Apart” – Daniel Pemberton (Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse)

- “The Sacred Pipe/Osage Oil Boom” – Robbie Robertson (Killers of the Flower Moon)

- “Can You Hear The Music” – Ludwig Gorannson (Oppenheimer)

- “Carmen Main Theme” – Nicholas Britell (Carmen)

Best Overlooked Performance

- Teo Yoo, Past Lives

- Rossy de Palma, Carmen

- Mads Mickelson, The Promised Land

- Alma Poysti, Fallen Leaves

- Bradley Cooper, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3.

Biggest Laugh

- Monk Being Stagg R. Lee – American Fiction

- Theater Scene – Fallen Leaves

- Paul Throwing the Football – The Holdovers

- Football Players Wearing Full Gear – Bottoms

- “You think you’re so great because you have boats!” – Napoleon

Best Directorial Debut

- Cord Jefferson – American Fiction

- Raven Jackson – All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt

- A.V. Rockwell – A Thousand and One

- Celine Song – Past Lives

- Kyle Edward Ball – Skinamarink

Best Editing

- Oppenheimer

- The Holdovers

- The Zone of Interest

- All of Us Strangers

- May December

Best Production Design

- Barbie

- Poor Things

- Fallen Leaves

- The Zone of Interest

- Asteroid City

Brendan’s Individual Special Awards

Best Performance by a Non-Human, aka “Cheddar Goblin” Award

- Messi the border collie, Anatomy of a Fall

- Chaplin the dog, Fallen Leaves

- Napoleon’s horse, Napoleon

- Snoopy, Maestro

Best Movie About Connection Between Two Lost Souls

- All of Us Strangers

- Monster

- The Taste of Things

- Fallen Leaves

- Past Lives

- Robot Dreams

- Godzilla Minus One

Best Insult

- “I’m from Waterloo where the vampires hang out!” – Blackberry

- “…you are and always have been penis cancer in human form.” – The Holdovers

- You think you’re so great because you have boats!” – Napoleon

Best High Concept Wasted

- Dream Scenario

- Cocaine Bear

- El Conde

- Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One

- Renfield

- Talk to Me

Best Performance by a Director NOT Playing Themselves

- David Lynch, The Fabelmans

Best Performance by a Monkey in a Movie About the Exploitation of Movies

- Gordy, Nope

- Mitzi’s pet monkey, The Fabelmans

Jay’s Individual Special Awards

Great Achievement Of The Year

- Jennifer Lame’s Editing in Oppenheimer

Movies You Most Forgot Came Out in 2023

- Strays

- You People

- 65

- Hypnotic

- Boston Strangler

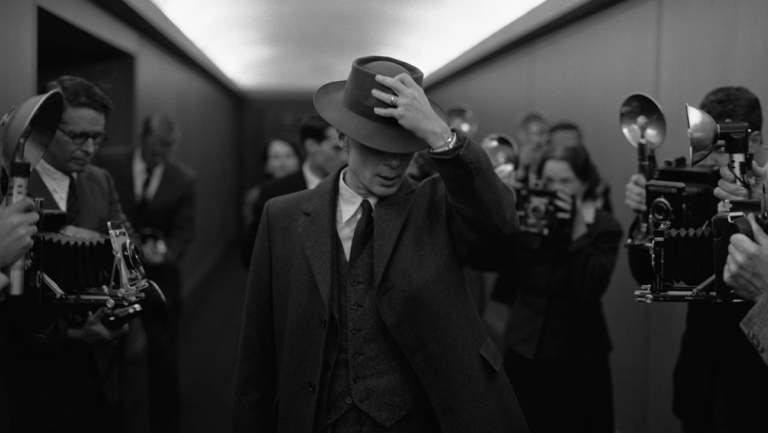

Hat of the Year

- Paul Giamatti’s Soft-Brimmed Hat

- Oppenheimer’s Wide-Brim Fedora

- The Killer’s Bucket Hat

The “Huh?” Award

- Shailene Woodley in Ferrari

I Can’t Quit You Award

- Guy Ritchie – The Covenant

The Tear-y (Most Tear-Inducing Film of 2023)

- The Iron Claw

- Past Lives

- Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

- Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3.

Uh Oh Spaghettios Award

- Whoever at Universal Brokered the $400 Million Deal For The New Exorcist Trilogy

- Supehero Movies

We’ll Give You A Pass Award

- Alden Ehrenreich, Cocaine Bear

Fever Dream Moment of the Year

- Scuttlebutt – The Little Mermaid

- Flash and the Babies – The Flash

- Wonder Woman Shows Up at Funeral – Shazam: Fury of the Gods

- Ray Liotta Has Guts Devoured – Cocaine Bear

- Zach Galifanakis Without Beard – The Beanie Bubble

The “Retire Please” Award for Directors Who Have Lost It (AKA The Zemeckis)

- Elizabeth Banks, Cocaine Bear

- David Gordon Green, The Exorcist: Believer

- Rob Marshall, The Little Mermaid

Ryan’s Individual Special Awards

Adam McKay “Please Stop” Award

- Sam Esmail, Leave the World Behind

“Did That Come Out?” Award

- Totally Killer

- Missing

- Renfield

- 65

- Boston Strangler

- Inside

- Operation Fortune

- Emily

- Magic Mike’s Last Dance

Brendan Cassidy Best Movie Trailer Award

- Argylle

- Madame Web

Well, that’s it for our 2023 InSession Film Awards! Hopefully, you all enjoyed our nominations and winners. If you agree or disagree with us, let us know in the comment section below. We would love to hear how your nominations and winners would vary from our picks above. You can also email your selections to us at [email protected] or follow us on social media.

To hear our Top 10 Movies of 2023, listen to Part 2 of Episode 576!