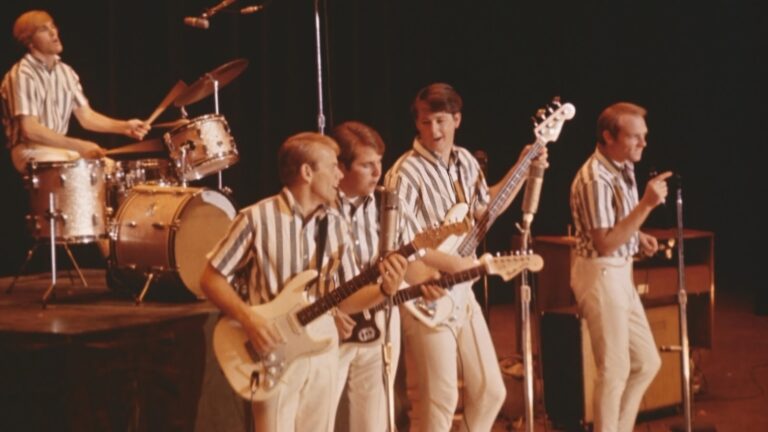

Director: Brad Peyton

Writers: Leo Sardarian, Aaron Eli Coleite

Stars: Jennifer Lopez, Simu Liu, Sterling K. Brown

Synopsis: In a bleak-sounding future, an A.I. soldier has determined that the only way to end war is to end humanity.

While watching Brad Peyton’s Atlas at home, the power went out twice in the span of five minutes. Now, I don’t much believe in higher powers, but I can’t help but think this was a sign from above to tell me to stop watching before my brain turned to complete mush. With all the issues I had during the film’s beginning in the hopes that my WiFi would reset before resuming the movie, my viewing ended much later than expected and I immediately went to sleep after the credits finished rolling.

I woke up the next day not remembering a single frame out of Atlas, as if the movie only existed in a fever dream and I hallucinated the entire thing. That can be the only explanation to muster up any comment on Peyton’s most listless film yet, an action sci-fi package that likely would’ve been pitched by Menahem Golan at the Cannes Film Festival, as he frequently told the plot synopsis of movies based on scenarios he would completely make up in his head without any intention of actually filming the damn thing.

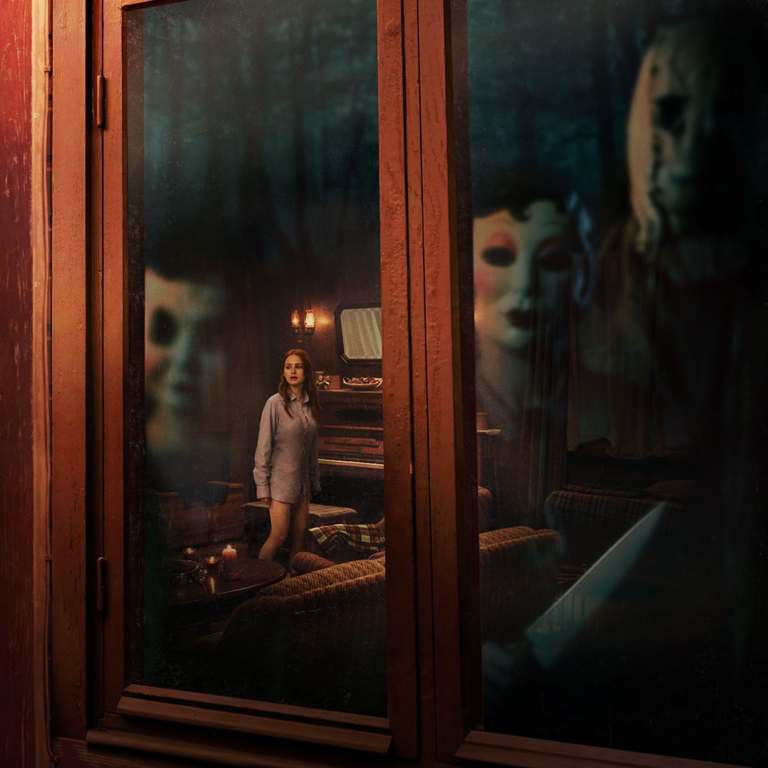

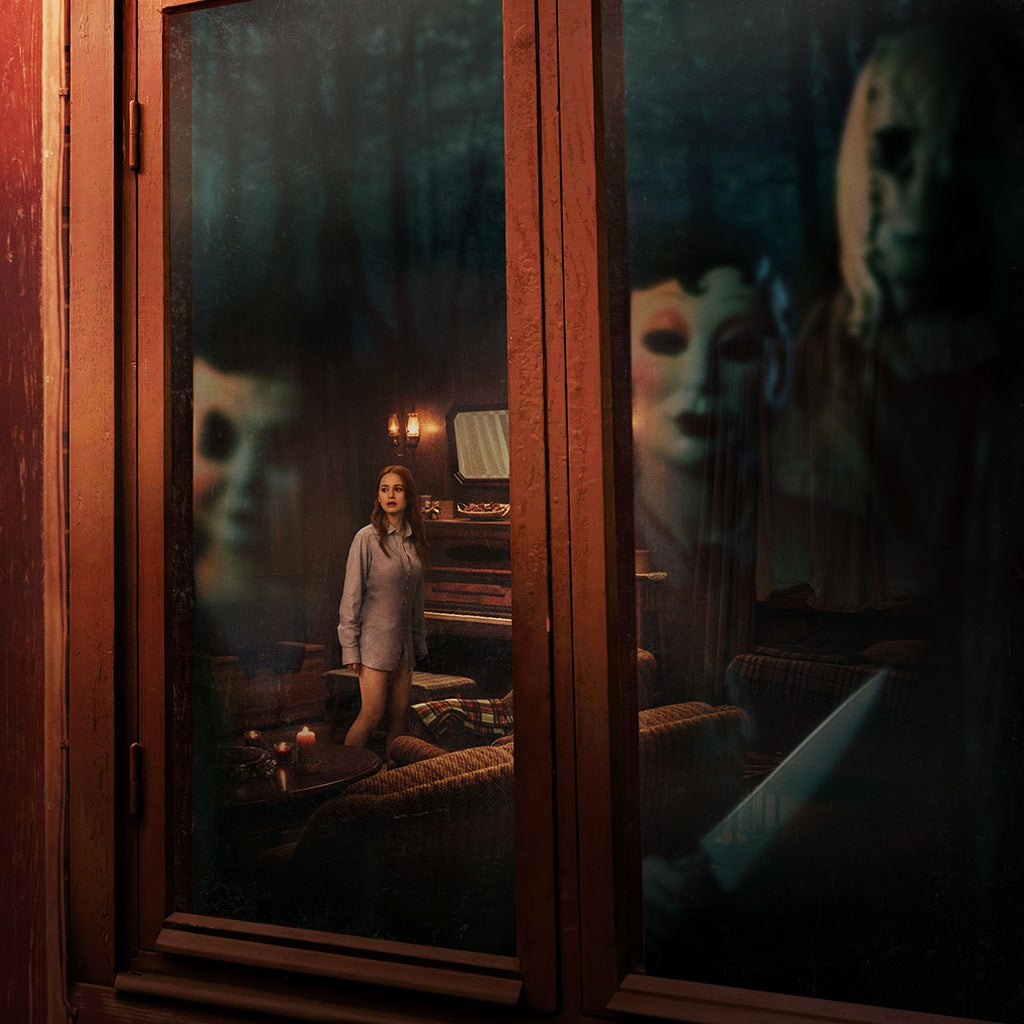

It’s a shame, because Peyton has proven in the past that he can direct good action in films like San Andreas and Rampage, and there’s a scene in its opening moments that proves he has the juice, with cameras hooked on machine guns and first-person shots of a tactile fistfight. That sequence put in my head that maybe this movie won’t be so bad after all, but it gets immediately hampered by barely-finished VFX with no sense of scale or depth as we get introduced to our titular character (played by Jennifer Lopez), a recluse scientist who fears the rise of AI after a sentient robot, Harlan (Simu Liu), killed her mother as a child.

Colonel Elias Banks (Sterling K. Brown) is assembling a team to apprehend Harlan after his location was revealed, and Atlas becomes an integral part of the mission. However, each member of the team is using an AI-powered spacesuit known as “Smith” (Gregory James Cohen), which Atlas does not want to use, or be close to.

Predictably enough, the team gets ambushed by Harlan and Atlas is forced to board a Smith to ensure her survival. The rest of the movie is an After Earth ripoff of Atlas being guided by Smith to arrive at Harlan’s base and destroy it, alongside him. Now, of course, After Earth wasn’t particularly good, but Shyamalan is far more willing in presenting interesting ideas to the screen, even if it doesn’t fully work, than Peyton, who wants to talk about AI without talking about AI. Let me explain: Artificial Intelligence is the subject of the moment, and the very rise of the technology in our everyday lives poses a real threat not only to our workforce, but also to humanity as a whole.

Exploring this in a movie is ever-timely, as the technology keeps evolving and taking much grimmer turns. AI is omnipresent during the opening moments of the movie, but the effects on such a technology is never fully developed, other than we know how much Atlas despises it, while everyone else embraces it. Peyton doesn’t develop this idea beyond that surface-level conflict, whether Atlas’ disdain of the technology or the reason why everyone decided to blanket embrace AI. That’s an interesting idea in and of itself, and one even wonders why someone would trust a technology that no one actively understands (even some of the most proponent supporters of AI, including Elon Musk and Yoshua Bengio, have asked for a pause on developing new AI experiments, though others like Yann LeCun have fully embraced it).

The only ‘real’ comment we get out of the proliferation of AI are that some softwares have humanized traits (such as one who specifies their pronouns being “she/her” and not “it”), and that AI is everywhere. Atlas thinks AI bad. Others think AI good. She will, at the end, think that AI is bad, except for Smith, because they will learn to (literally and figuratively) bond inside a Spy Kids 3D: Game Over-like spatial environment with shoddy-looking visual effects and a complete lack of proper shot composition.

There isn’t a single image of note in Atlas, and the film will never once overcome its “fake movie” allegations, with characters so thinly-developed and poorly acted you would think they signed up to do an elongated SNL parody, which would be the only way to describe the out-of-body experience you’ll have watching this. There would be no other way to qualify Liu’s stilted, hysterically awful performance as Harlan, a villain whose motivations can only be summed up to “blow up the world and kill Atlas,” instead of something far more psychologically active, which the best AI villains have always been. He does kick some ass during the finale’s Dragon Ball Z-inspired fight scene, but it’s not enough to make him a fully-fledged antagonist, whereas Lopez completely phones it in through its green screen-laden environments and action scenes directed by its visual effects team.

There’s no rhythm or energy in anything going on. We barely learn who these people are for us to truly latch onto them and create a meaningful connection with the protagonists, which are at the heart of every good science-fiction story. If we’re going to spend TWO HOURS of our time, and most of it with one character, I expect the titular protagonist to be developed, or at least as relatable as possible. But we’re a long way off Lopez’s incredible performance in Hustlers, knowing full well this will be another cog in the Netflix algorithm that will be as easily forgotten as her previous actioner, The Mother.

At least that movie had some bold narrative swings that made the entire experience feel surreal, whereas Atlas has virtually nothing of note to offer. None of the acting is particularly interesting, the visual effects are completely unconvincing, the action continues the CGI blob pandemic that’s unfortunately been plaguing most of our blockbusters, and Peyton never delves into some of the ideas that could make this piece of science-fiction feel excitingly relevant, asking pertinent questions on the use of Artificial Intelligence in our everyday lives and how we can examine its arrival in a less frightful, but apprehensive light.

AI isn’t all bad – I certainly enjoy using otter.ai to transcribe interviews (especially in this busy Emmy FYC season), but it’s also not all good. This moral grey area seems to be at the center of Atlas, yet Peyton never has the guts to do anything with it. He would rather fill the screen with mind-numbing images that never look real enough for me to care and immediately forget as soon as I begin to fall asleep. I’ll only remember the time I had watching it, with two divine interventions telling me to stop before I continued on and felt absolutely nothing for two very long, very dull hours.