As the nights grow longer and the air turns crisp, spooky season sweeps in like a delightful ghost. For horror fans, this is the perfect time to gather around the flickering screen, reliving old scares and discovering fresh nightmares. Among the iconic figures haunting the genre is the fabulous Janet Leigh, the original scream queen. Her unforgettable performance in Psycho didn’t just leave audiences trembling; it shattered boundaries and redefined how women are depicted in horror. Her haunting scream still resonates through the ages, a beautiful reminder of the genre’s timeless power and allure.

A Personal Encounter with Psycho

I still remember the first time I watched Psycho like it was yesterday. I was around 12, curled up in my dimly lit room late at night, a cozy little haven perfect for a horror marathon. My grandmother, a true lover of classic films, had often regaled me with stories of how Psycho shocked audiences when it first hit the screens. She even mentioned the infamous shower scene, but I thought I was ready for it. Little did I know, nothing could truly prepare me for the raw intensity of experiencing it all myself.

Alfred Hitchcock had this magical way of building tension so gradually that I felt completely immersed, as if I were right there with Marion Crane, making choices I instinctively knew were headed for disaster. Every little detail added to the suspense, and my heart raced as I sensed something dark lurking just beneath the surface.

Then came the shower scene, and oh my goodness, it caught me completely off guard! The sudden rip of the curtain felt like a jolt, and Janet Leigh’s chilling scream echoed through my room, freezing me in place. It wasn’t just the shock of the violence; it was the heart-stopping realization that the story had taken such a sharp, unexpected turn. I had thought Marion was the protagonist—how could this happen to her? That scene didn’t just terrify me; it fundamentally changed how I viewed horror films.

I realized that it wasn’t always about blood and jump scares; it was about moments that really unsettle you on a deeper level, making you question everything you thought you knew about the characters and their fates. Even now, years later, that scene still sends shivers down my spine. It was my first real introduction to psychological horror, where the fear doesn’t come from supernatural creatures but from the terrifying unpredictability of ordinary people.

Psycho taught me that horror could tap into real emotions, reflecting those little anxieties we carry around with us—like the fear of losing control or the dread of the unknown. That’s why I fell head over heels in love with the genre. Horror isn’t just about monsters lurking in the shadows or gruesome gore; it’s about confronting the raw, emotional vulnerabilities we often keep hidden away. In a way, it’s cathartic. It forces us to face our deepest fears, pushing us to confront what scares us most, both mentally and physically.

So here I am, still enchanted by those spine-tingling moments in horror, thanks to that unforgettable first encounter with Psycho. It opened my eyes to a whole new world of storytelling and emotion, and I wouldn’t trade that experience for anything.

Leigh’s Performance and the Cultural Context of the 1960s

Janet Leigh’s portrayal of Marion Crane in Psycho was a groundbreaking moment for women in horror cinema, setting her apart from the usual passive female characters of the time. Rather than simply being a damsel in distress, Marion is introduced as a fully realized individual, navigating personal dilemmas with agency and depth. Her decision to steal money in a bid to break free from a mundane life reveals her complexity, making her more than just a plot device for the male characters. Leigh’s performance brought a raw vulnerability to Marion, giving audiences a character whose emotional struggles were not only relatable but also significant, adding a new dimension to the horror genre by placing a woman’s moral and existential conflict at the center of the story.

This shift in representation was a reflection of the broader societal changes occurring in the 1960s. The decade saw the rise of the feminist movement, which challenged traditional gender roles and pushed for women’s rights and autonomy. Marion’s inner conflict—caught between societal expectations and her personal desires—mirrored the experiences of many women at the time, making her character feel revolutionary. Leigh’s nuanced performance emphasized this struggle, aligning with the growing cultural discourse about women’s roles, independence, and the consequences of challenging the patriarchal norms. The fact that Marion’s choices were given narrative weight, and her life was treated as consequential, signified a break from the male-centered storytelling that had long dominated film.

Leigh’s depiction of Marion Crane, and her ultimate fate, resonated deeply with the feminist undercurrents of the era. While Marion’s journey ends tragically, her character’s complexity and agency were a step forward in how women could be portrayed on screen. Her struggles underscored the need for more authentic, multifaceted female characters—women who were not just victims or archetypes, but who had their own narratives, desires, and conflicts. Marion’s role in Psycho became a turning point, reflecting the growing demand for richer portrayals of women in cinema, just as society was beginning to reexamine the traditional roles women were expected to play.

The Atmosphere of Horror: A Chilling Experience

The atmosphere of Psycho serves as a masterclass in suspense and horror, immersing viewers in a world where tension is palpable and dread lingers in every frame. From the moment the film begins, the carefully crafted score, composed by Bernard Herrmann, envelops the audience, amplifying feelings of unease and anticipation. Shadows play across the screen, and the meticulous use of light and darkness creates a claustrophobic environment that mirrors Marion’s psychological descent. This atmospheric tension is not merely a backdrop; it is integral to the storytelling, heightening the stakes as Marion navigates her precarious situation.

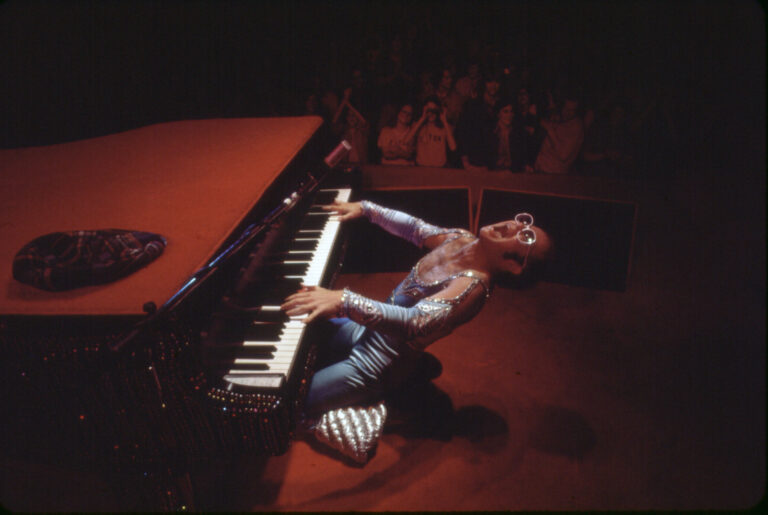

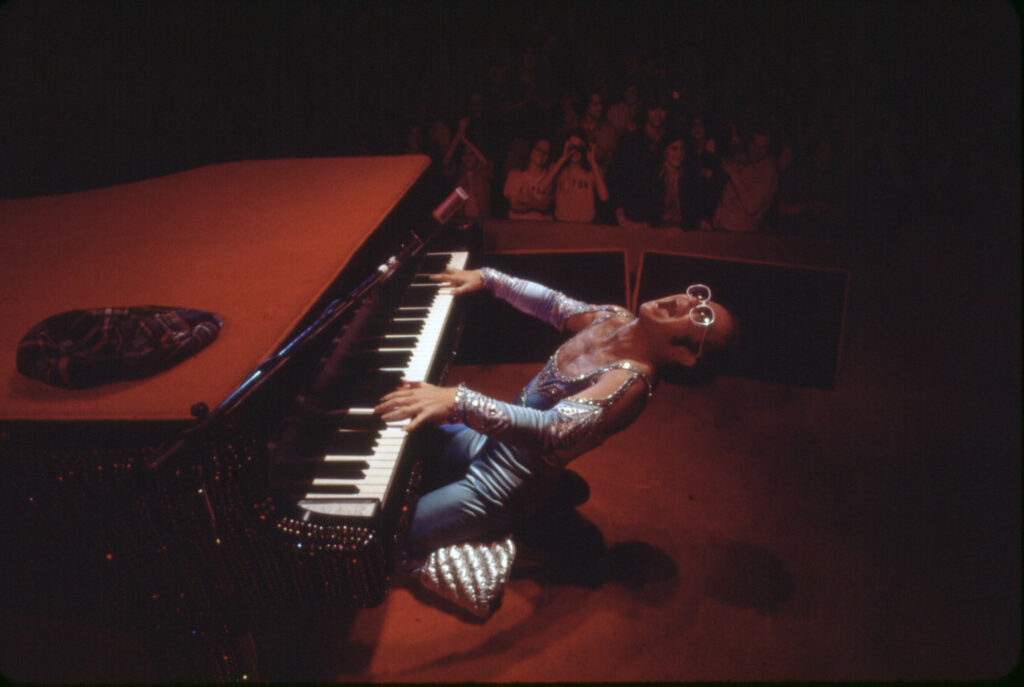

One of the most iconic moments in cinematic history is undoubtedly the shower scene, where Janet Leigh’s performance reaches its zenith. The scene is not just a moment of horror; it represents the culmination of Marion’s vulnerability and the brutal reality of her circumstances. Her scream, as sharp and piercing as the knife in the killer’s hand, reverberates through the collective consciousness of film history. It symbolizes not just a moment of terror, but also a profound commentary on the experience of women throughout history—facing violence, often in silence and isolation. Leigh’s ability to convey raw fear and vulnerability in that moment encapsulates the broader anxieties women faced in a society that often relegated them to the role of passive observers in their own narratives. This iconic scene has become a touchstone in horror cinema, influencing countless films and solidifying Leigh’s status as the original scream queen.

Modern Horror’s Connection to Leigh’s Legacy

Horror continues to evolve, but its roots can still be traced back to Janet Leigh’s iconic role. Films like Hereditary and Midsommar carry forward the psychological horror tradition that Hitchcock’s classic helped shape. Whereas Psycho relied on sharp, shocking moments to create fear, today’s horror often takes a more subtle, creeping approach. Modern films build tension gradually, allowing fear to grow beneath the surface, mirroring the internal struggles of their characters. Much like Marion Crane, the protagonists of these stories are not just victims of external forces but are grappling with their own emotional and psychological turmoil. This shift allows for a more profound exploration of themes like grief, trauma, and family dynamics—ideas hinted at in Leigh’s portrayal of a woman caught between moral conflict and personal crisis.

Modern horror also gives its female characters greater depth, moving beyond the traditional survival archetype. In Hereditary, Toni Collette’s Annie Graham is burdened by her family’s dark legacy, weaving a terrifying narrative around maternal anxiety and inherited trauma. Midsommar similarly delves into the grief of Florence Pugh’s Dani Ardor, following her emotional journey as she reclaims power and turns her pain into strength. This shift speaks to a growing recognition of the complexities of women in horror, a progression that began with characters like Marion Crane. Her legacy lives on, not just in the characters who followed but in the way horror now creates space for women to confront their fears, reclaim their stories, and redefine the genre’s boundaries.

Breaking the Boundaries of the “Final Girl” Trope

The “final girl” trope has long been a cornerstone of horror, presenting audiences with a heroine who stands tall against the terror she faces, often outsmarting and outlasting her pursuers. While it has been celebrated for empowering women within the genre, the trope has also been critiqued for frequently linking female survival to notions of purity and moral virtue. Some classic slasher films, like Halloween and Friday the 13th, reinforce this idea by portraying the final girl as more innocent or virtuous than her peers, who are often punished for engaging in behaviors like drinking, drug use, or premarital sex. This has led to the interpretation that survival hinges on adherence to traditional moral values.

However, this reading isn’t universally applicable across all horror films. In Men, Women, and Chainsaws, Carol J. Clover coined the term “final girl” to describe a female protagonist who survives the film’s climax after confronting the villain. While some films do follow the pattern of linking survival to purity, it’s not an inherent rule of the trope. Many final girls survive because of their intelligence, resourcefulness, and determination—qualities that have nothing to do with their innocence.

As horror has evolved, modern films have increasingly moved away from the rigid confines of the final girl’s supposed moral purity. Movies like The Witch, Ready or Not, and Sydney Sweeney’s Immaculate challenge traditional tropes by offering complex female characters who defy the old rules. These protagonists aren’t surviving because they conform to a specific ideal—they survive because they take control of their fates, face danger head-on, and refuse to be victims. They shatter the mold, rejecting the notion that survival depends on purity, and instead, showcase strength, resilience, and depth.

Janet Leigh’s portrayal of Marion Crane in Psycho also paved the way for complex, flawed female characters in horror. While Crane is not a “final girl” in the traditional sense—her shocking early death subverts expectations entirely—her character is emblematic of how female roles in horror have evolved over time. Psycho set a precedent for breaking conventions, challenging audience expectations, and expanding the scope of what women in horror could represent.

Neve Campbell’s portrayal of Sidney Prescott in Scream is a shining example of this evolution. Sidney doesn’t just endure—she critiques the very genre she inhabits, subverting the tropes that often limit female characters. Mia Goth in Pearl takes it even further by exploring identity and ambition in unsettling, bold ways, while Sydney Sweeney in Immaculate confronts personal demons and faith, demonstrating the complexity and depth of modern horror heroines.

These performances represent a significant shift in how women are portrayed in the genre. No longer boxed into one-dimensional survivor roles, they embody multifaceted experiences that resonate deeply with audiences. Modern horror is no longer content with female characters who simply play by the rules—these women are rewriting them entirely. The evolution of the “final girl” shows that survival is not about moral virtue but about strength, willpower, and the ability to navigate the darkest corners of fear.

Expanding Representation in Horror

While Janet Leigh’s scream opened the door for more nuanced portrayals of women in horror, it is essential to recognize that the genre has historically marginalized women of color and LGBTQIA+ characters. For too long, horror has predominantly featured white, heterosexual women as its focal points, sidelining the rich tapestry of experiences that exist within marginalized communities. However, recent films such as Candyman (2021) and His House signify a much-needed shift towards inclusivity, allowing underrepresented voices to craft their own narratives of fear and resilience. These films not only diversify the stories told within the horror genre but also bring attention to the unique struggles faced by individuals from different backgrounds, enriching the overall landscape of horror storytelling.

This evolution towards more inclusive representation is long overdue, reflecting a broader societal recognition of the diverse experiences that shape our understanding of fear and survival. The genre’s ability to adapt and incorporate varying perspectives speaks to its resilience and relevance. By expanding the narratives within horror, filmmakers can explore themes that resonate on a deeper level, illuminating the complexities of human experience and the many ways individuals confront and overcome their fears. As horror continues to evolve, it increasingly mirrors the society we live in, challenging traditional norms and creating space for varied voices and stories that resonate with a wider audience.

The Scream Queen Legacy

As you gear up for your annual spooky season binge, it’s the perfect time to reflect on the lasting impact of scream queens throughout horror history. Which performances have left a mark on your understanding of the genre? How do these roles mirror the shifting landscape of horror, and what does the future hold for female representation in this space? Engaging in this conversation not only honors the legacy of Janet Leigh and her contemporaries but also acknowledges the evolving narratives that continue to shape our understanding of fear, resilience, and empowerment.

Janet Leigh’s portrayal of Marion Crane is a pivotal moment in film history, with her legacy as the original scream queen still inspiring and influencing horror films today. As we dive into the thrills and chills of our favorite fright flicks this Halloween, let’s not overlook the significance of her haunting scream and the stories it tells. So grab your favorite drink, dim the lights, and pay homage to the woman who forever transformed the landscape of this genre. Each scream, whether echoing from the past or resonating in today’s films, holds a tale waiting to be uncovered—one that deserves to be celebrated. Embrace the enchanting spirit of the season, and let the timeless legacy of Janet Leigh guide you through the eerie corridors of cinematic history, inspiring future generations of filmmakers and fans alike.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/The-Friend-Naomi-Watts-083124-03-ceef5de62a6745339ac59b737659de8c.jpg)