Directors: R.J. Cutler, David Furnish

Stars: Elton John

Synopsis: It showcases a never-before-seen concert footage of him over the past 50 years, as well as hand-written journals and present-day footage of him and his family..

Elton John is a special artist and performer. He may be one of the best showmen music has ever had. And everything he brought us via his artistry’s presentation will never be replicated. I highly doubt that there will be another like him in the future. His blend of rock, blues, funk, and pop styles charmed the world with his beguiling, dazzling records like ‘Bennie and the Jets,’ ‘I’m Still Standing,’ and (one of my favorites) ‘The Ballad of Danny Bailey.’ Elton John is a chameleon, an artist who is always willing to experiment with his form via his influences–The Beatles, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, etc. A child prodigy on the piano who became one of the most impressive musical acts to cross the earth.

In my household, a lot of Elton John’s music is heard; the entire family has playlists of his music, and there are even a couple of vinyl records here and there. So, when I heard that a documentary about him was going to be screened at the New York Film Festival (in the Spotlight section), I wanted to take some time off from watching international arthouse films to check out R.J. Cutler and David Furnish’s Elton John: Never Too Late. Unfortunately, the documentary does not add much to the legend’s story or explore the process behind the Rocketman with rose-tinted shades. It leaves the project alongside the many biographical portraits made by big studios. While one might be charmed by it all due to Elton’s persona, the project lacks deeper insight and interest.

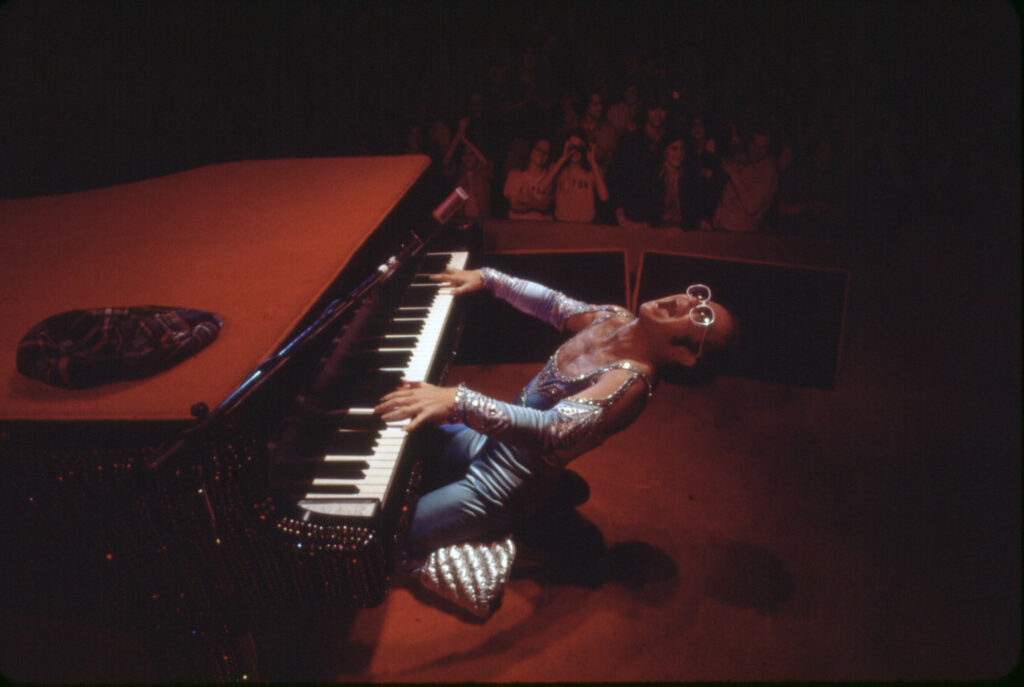

Cutler and Furnish have plenty of material at their disposal from five decades worth of shows, recordings, and behind-the-scenes footage that capture the essence of Elton John. But, without a clear vision for the project based around him, you have a lot for nothing–everything available, yet not knowing what to do with it. Never Too Late is tied together by two performances at Dodger Stadium in different eras: the height of his career in the mid-’70s and the potential end of his live performances in 2022. If you love his music or have seen the film Rocketman, you know about the former. It was a two-night event in 1975 where 110,000 fans got crammed in Dodger Stadium, as Elton wore the baseball team’s uniform with plenty of sparkling lining. The latter was fairly recent, during his Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour–the curtain closer to his legendary career of magnificent showmanship.

Initially, you have the connective tissue of a man looking back when his career peaked, creatively and commercially, and pondering what comes next when he retires. However, within these two critical moments in his career, the documentary starts developing two new narrative strands that talk about his beginnings as a trained classical music student in England to his grand farewell all over the world–the start and finish of the Rocketman. The start of Elton John has been documented many times. Even Dexter Fletcher planted it in his 2019 biopic starring Taron Edgerton. The aforementioned shows his start through the vivacity of Elton’s records, which contrasts with his repressed childhood, which he had artistically and his time backing bands like The Drifters.

Meanwhile, in Never Too Late, you never feel vivacity and spirit from the artist’s interviews. His journey is still fascinating; how Elton grows from classical music to a multigenre mash-up composer is very impressive–everyone who aspires to be a musician must read about him to get inspired. Yet, in the vacuous way it is approached here, it does not capture that magnificence. You only sense the grandeur of his musical aura via the performances we see, both old and new. Examples that come to mind are a cover of The Who’s ‘Pinball Wizard ’ and John Lennon’s last performance in America during Elton’s 1974 concert–the ex-Beatle’s ability to move a crowd and Elton passing the spotlight to someone else. As a slight gift and a shift in tone, we see an animated sequence of the two stars partaking in some substances.

There are some personal scenes in which Elton delves into the abuse, both by drugs and his parents, he faced during his teenage years and the height of his career. People like Winifred Atwell, Bernie Taupin, John Reid, and Roy Williams are mentioned throughout this section of the film–all riddled with painful angst that took their lives into dangerous, isolated territories. These moments in Never Too Late show the true purpose of the documentary and why Cutler and Furnish made it. The title, taken by the track of the live-action Lion King film of the same name, may recall the availability to change, whether it is referring to something you want to fix or make amends to.

In the documentary, Elton refers to it as a means to reflect on the past and guide his loved ones–his partner and kids–so they can avoid his deeply wounding woes. That’s why he wants to retire. He wants to be in their lives, support their decisions, and care for them, unlike his own parents. Elton glances at the past with new eyes that are clearer about everything that happened. While the majority of the doc does not contain that personal emotional heft, these moments do have Elton showing some vulnerability, just like he does in his best and most memorable records. In the modern era part of the doc, little emotion is felt, and most is hidden. The element of looking back to pave the way for the future is lost amidst very unimportant ramblings. You don’t get anything out of it, even if you are a fan.

For lack of better words, it feels safe and clean rather than open and sensitive. You would expect more playfulness behind the camera and experimentation with the information provided for a man like him, with a discography filled with glitz and glamor. A film like Moonage Daydream by Brett Morgen comes to mind–a kaleidoscopic roundabout through the different eras of a musical genius. You see what Morgen did with all access to archive footage. And in comparison, Never Too Late reeks of uniformity and flavorlessness. Nothing feels cinematic, and it infuriates me that many documentaries on iconic artists always end up as weak efforts due to the filmmaker’s inability to capture their music’s impact through style and importance rather than a thorough examination.

When Alex Ross Perry made Pavements (playing at the festival in the same section), he said that he wanted to pave the way for directors to craft more inventive portraits of musical figures with flair and ingenuity–projects rooted in the acclaimed that made the artist(s)’ style and musical posture. And it feels odd that such a film like Never Too Late plays next to Pavements, a project with tons of purpose and dedication that shows the band’s history and acclaim through many cinematic tricks and innovations. They feel like polar opposites of what can be made by visionaries and studio heads. Cutler and Furnish have open doors to access the sparkling world of the Rocketman, yet decide to delve into the old, tired traits of uninspired biographies and portraits made in today’s age