Director: Louise Archambault

Writer: Dan Gordon

Stars: Sophie Nélisse, Dougray Scott, Andrzej Seweryn

Synopsis: Follows the life of a Polish nurse Irene Gut Opdyke who was awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal for showing remarkable courage in her attempt to save Polish Jews during World War II.

There are so many stories of heroism in the face of the despotic Nazi occupation of Europe during World War II that it’s easy to think that all the stories are simple, but Irena’s Vow proves that there can still be a few unheard stories that are as unique and important as many that have already been told. The film is already one leg up on most others because its focus is on a woman who stood up to tyranny all on her own.

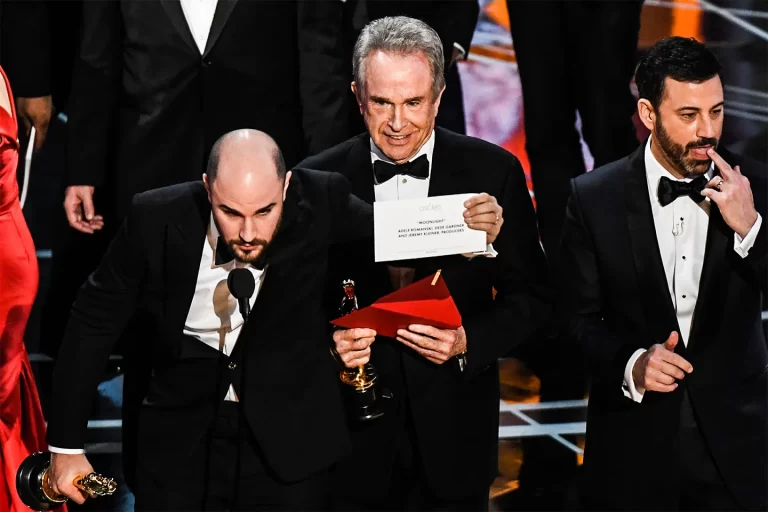

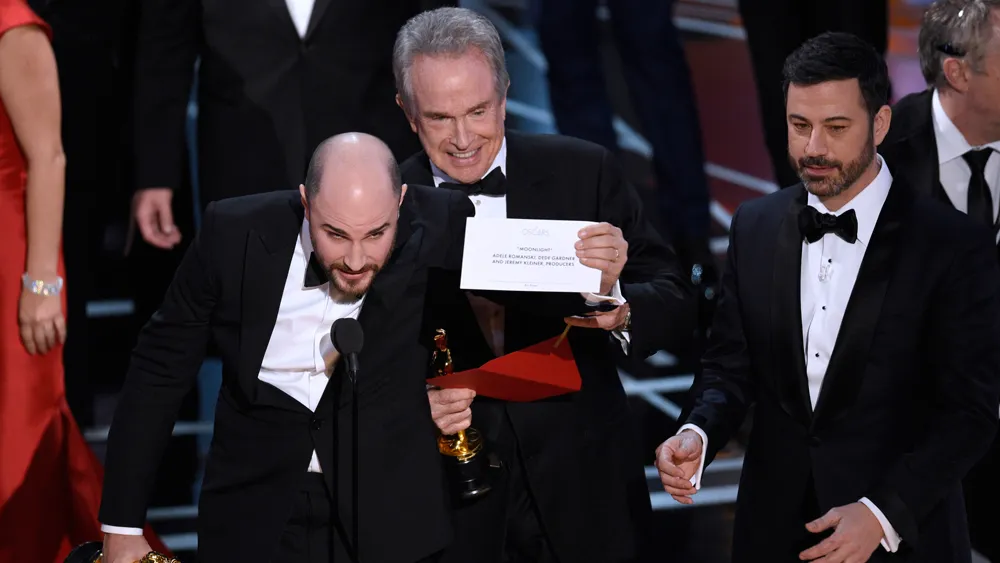

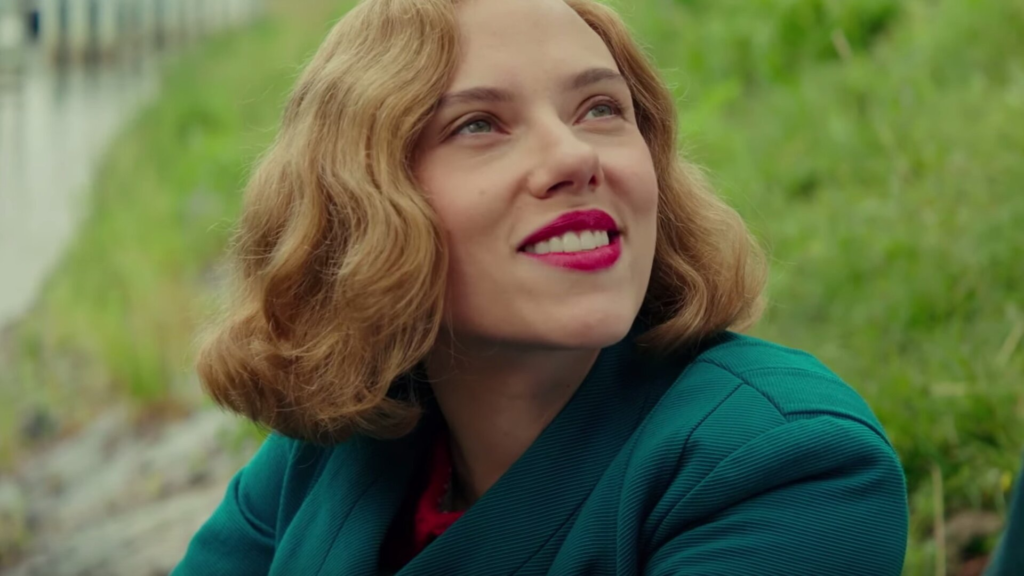

The film is driven by the stellar performance of Sophie Nélisse as Irena Gut Opdyke. Her ability to play subterfuge and a constant anxiety over her charge’s welfare is fabulous. She has an expressive face and large eyes that convey many grand emotions in every scene. She carries the film through each worsening lie she has to perpetrate in order to protect those she is hiding.

The lies are intriguing and border on farce. When she has people in to clean the villa before Major Rugmer (Dougray Scott) moves in, she has to deftly maneuver the workers outside for a picnic so her charges can move quickly from the cellar to the attic for the cellar cleaning. She has to explain away extra dishes and how she can serve guests at a party and cook the entire meal herself. She drugs Rugmer in order to shift the people she’s hiding from one room to another. There is a scene in which Rugmer wakes up at night, because he hears small scratching sounds in the cellar. He doesn’t find anything, but when Irena comes in to get the breakfast started he calls for exterminators because they have rats.

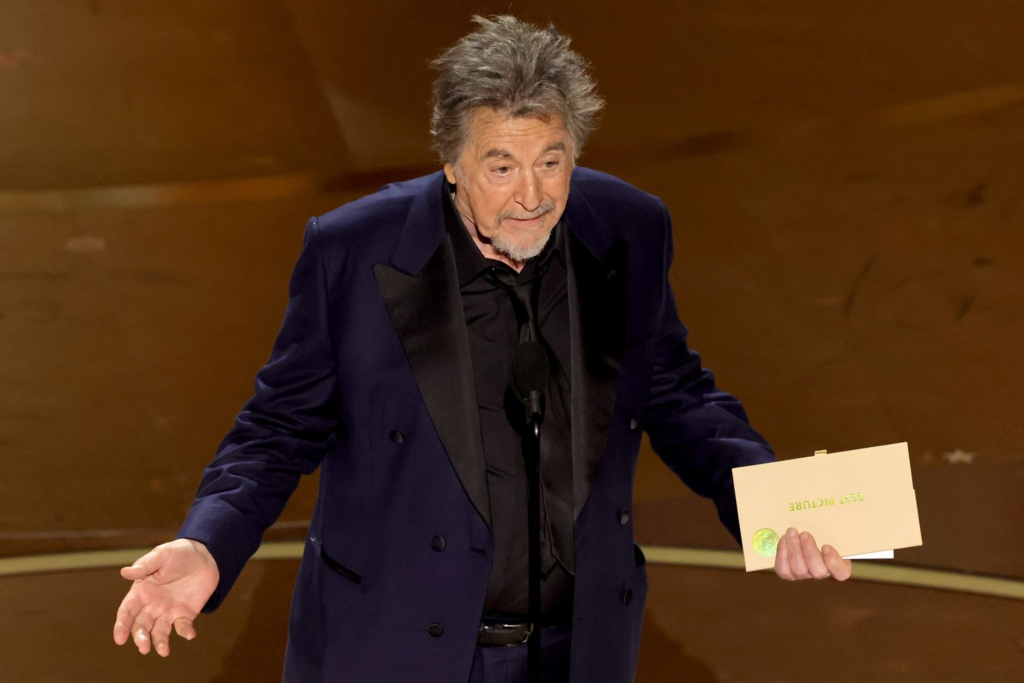

It feels as if Dougray Scott’s performance veers too far toward humor in many of the scenes he’s in. He becomes a bit hammy at times as the shouting, fussy Nazi commander who is somehow blinded to what’s going on in his house. It’s almost as if he read the script as a Jojo Rabbit more than a Schindler’s List. That may be a fault of Louise Archambault’s direction as well, though, as some of her other scenes have a strange tonal dissonance between character and scene, especially where Nazis are concerned.

While Archambault should be praised for her disinterest in wallowing in her most violent scenes, the scenes themselves are undercut by the mustache twirling villain of the film, SS officer Rokita (Maciej Nawrocki). This criticism is not meant to undercut the actual atrocities perpetrated by Nazis on the civilian populations. There were horrific crimes committed by these horrific men and we can’t forget the truth of what they did in the name of white supremacy. Yet, the point could be made without going toward Hans Landa villainy when Amon Goeth’s evil was just as cruel, but far less Snidely Whiplash.

Rokita brutally executes someone in the streets, which is one of the catalysts for Irena wanting to help, but his second scene of terror is more horrific and unsettling. He forces civilians to watch as he hangs the family of Jews, children and all, with the family of Poles that harbored them, also children and all. The scene is effective as a warning for Irena, but when it lingers on Rokita’s perverse glee even focusing on his lazy conducting of the music that plays, it shifts into far stranger territory that detracts from the story at hand.

In spite of these sort of tonal shifts, the film is well made. One particular scene is a fabulous alchemy of Archambault’s direction, Paul Sarossy’s cinematography, and Arthur Tarnowski’s editing. As Rugmer throws a Christmas party upstairs, the Jews in their hiding place light candles and sing for Hanukkah. The Christmas festivities turn from an aggressive singing of “O Tannenbaum” into a bacchanalia of jazz and drink and the muted celebration below becomes emotional as the people remember more songs and think of the family they left behind. It’s a terrific companion sequence as those in hiding wait out the fall of the empire that they can see will come any day now from the papers smuggled down to them.

Irena’s Vow is an intriguing thriller that will keep you interested. While the Nazi’s antics are a bit of a distraction, Irena’s journey is enough to keep the movie well above water. The film is tense, heartbreaking and, in the end, full of hope. Irena’s Vow is a World War II civilian tale that is more than just a historical record, but a harrowing saga as well.