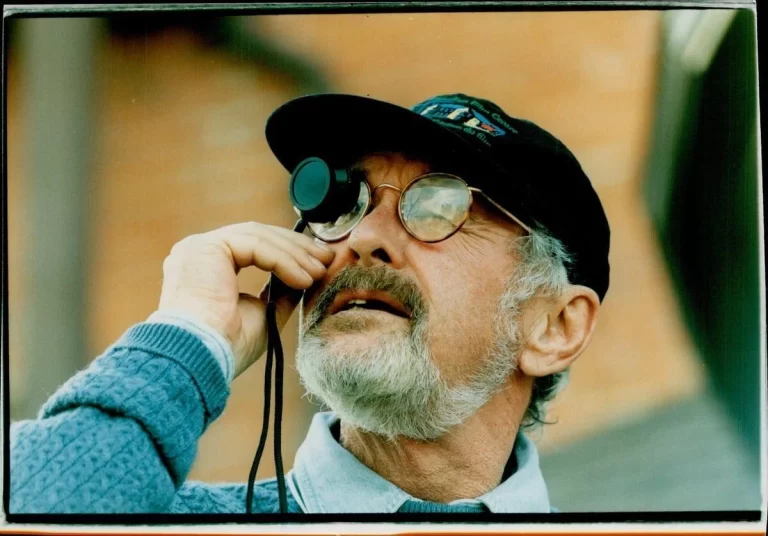

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers: Martin Scorsese and Eric Roth

Stars: Leonardo DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone, Robert DeNiro

Synopsis: Members of the Osage tribe in the United States are murdered under mysterious circumstances in the 1920s, sparking a major F.B.I. investigation involving J. Edgar Hoover.

“Can you find the wolves in this picture?”

In Martin Scorsese’s epic tale of the murder and torture of the Osage people in the 1920s, there are, indeed, many wolves to be found. But, as in life, they are never who they seem to be. Of course, if you know your American history, they will be easier to spot. But the people most affected by this story, the Osage, did not have that particular privilege. Their story here begins in pain, forced off their land and accepting the fact that their children will not learn their ways. Their piercing wails say more than any dialogue could ever muster. However, after miraculously striking oil on their new land, everything changes for the Osage. They become some of the richest people in the country. They have finery, and some level of power. But money does not equal equality and, over time, they intermingle with white people in this new land.

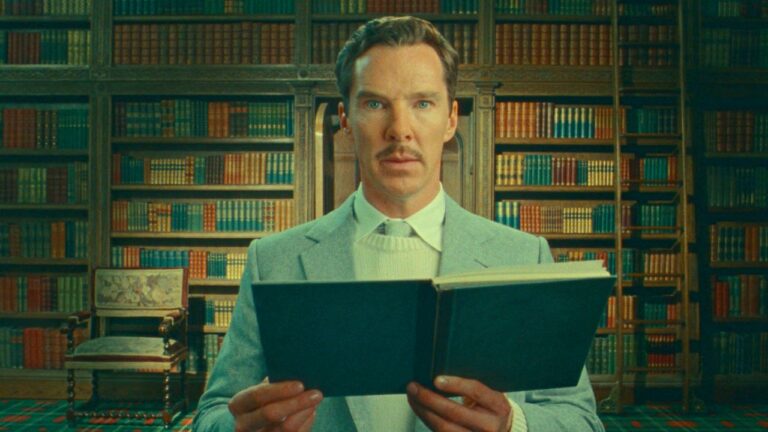

Killers of the Flower Moon, at first, is a simple love story. Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), after returning home from the war, without engaging in combat, lives with his uncle, William “King” Hale (Robert DeNiro). Here, he is shown how things work. The Osage have rights to property and money in the town, but there are opportunities to marry into this advantage. Dicaprio, playing a simple man, his jaw jutting in mockery of his movie star good looks, meets and quickly falls in love with Mollie (Lily Gladstone). Scorsese’s gift, in this first act, is to make us feel for Ernest, and believe the love story between him and Mollie. Both DiCaprio and Gladstone shine in these sequences, their smirking flirtation creating heat, even without much physical contact.

Scorsese and his production designer, Jack Fisk, seemingly build every set from the ground up, including Mollie’s house. This sense of lived-in authenticity creates a comfort that allows us to slide into this world with an easy grace. Additionally, the music created by the late Robbie Robertson creates the heartbeat of this very real story of almost unbelievable pain and loss. Scorsese is able to create a world that is both separate from us and able to focus on lives that are given an inherent arc and depth.

This initial love story, though wildly convincing, is quickly replaced with a world that absolutely sees color. The use of the Tulsa Race Massacre to help us understand that white supremacy, especially in the 1920’s will not allow non white people to gain real power, especially power not shared. Master editor Thelma Schoonmaker is able to weave this footage into the process of the film so expertly, that we feel it in the present moment. It is important to note the duplicitous nature of apparently kindly characters, as opposed to those involved in Tulsa. Scorsese makes a point to focus on characters who seem to be connected to Native people and their actions. King Hale, specifically, acts as a friend, even sitting with them in their pain, and yet, behind the scenes, he is a different man entirely. Don’t let his disapproval of the KKK fool you, he is simply careful to keep his hands clean while doing the same work.

For all of his faults, and there are many, Hale does have awareness of exactly who he is. He is shrewd, cunning, and understands people. Ernest, in a sense, is his opposite. He believes that he is a good man, as most of us do. But he is foolish, and easily manipulated into doing the next wrong thing. Ernest truly believes that his actions are not hideous, are not manipulative, and are not evil. Scorsese and Eric Roth, pen a screenplay (based on a novel by David Grann) that creates an incredibly specific trick. They help us understand the reasoning behind Ernest, while also never letting him off the hook. Much of this can also be attributed to the transcendent performance of Gladstone. She takes a character that could have been relegated to the role of victim, and imbues her with strength, conviction, and deep soulful sorrow. Her performance here is unforgettable. Although, yes, Killers of the Flower Moon, is from the perspective of rotten white men, it is her story that is lasting in our minds.

Scorsese, unlike in previous iterations of stories of greed, refuses to let his audience consider being on the side of the monsters. Without giving much away, he actually shows unflinching torture of a people, without giving in to a tendency to glorify the violence. Given that it is a movie about numerous murders of Native people, it is a subtle piece of work, in terms of violence.

But that subtlety does not hide the monster of white supremacy. At two different points, the script makes a point to mention that the white man’s actual guts are to the point of bursting. Their insatiable greed and assumed right to riches compels them to devour. They devour until they are metaphorically vomiting Native blood and oil. In one particularly memorable scene, King Hale continues to use his knowledge by having fire set to his property to gain insurance money. Scorsese and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto create a horrific, nearly satanic, sequence featuring DeNiro quietly watching from safety as the world burns and lackeys do his bidding. He seems to be above reproach, no matter what disgusting acts he puts into motion.

Martin Scorsese seems obsessed with terrible, evil men. He reckons with our ability to destroy one another, seemingly with ease. He, and the film, sets up a possibility that these men will have to reckon with their actions by the time the credits roll. Instead, he cleverly removes context of the ending of the film and forces us, the audience, to reckon with the role we play instead. Terrible things have indeed occurred throughout history. Are we doing anything to change that in the future? Or are we simply devouring their pain greedily?