The following piece contains frank discussions of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. If this type of discussion tends to upset you, please take care before continuing to read this piece.

WALT

I hope the roof flies off, and I get sucked into space. You’ll be better off without me.

LAURA

Stop feeling sorry for yourself.

WALT

Why?

LAURA

[sighing] We’re all they’ve got, Walt

WALT

That’s not enough.

We can sometimes see a physical manifestation of someone’s feelings. There are those of us who have a hard time not looking like how we’re feeling no matter how hard we try. We simply exude pain, joy, exhaustion, anxiety, fear, anger, and contentedness. It’s hard to tell what a character in a Wes Anderson film is thinking when we first meet them, they often have their faces at rest, but it’s likely they’re experiencing depression. Anderson builds this very human condition of being depressed into each and everyone of his films in some way. It ranges from mild ennui to ideations and attempts of suicide. For most Anderson characters, their grief cycle begins with depression. It’s how they experience the initial loss, whatever it may be.

In that case, this could be why people experience these films as cold and emotionless. The characters are often cynics and sometimes curmudgeons, but many are ambitious and passionate as well. What sets them apart is that these characters don’t learn life lessons that help them to be less sad. They start sad and they end sad. These films are about people attempting to cope. Some, like Herman Blume (Bill Murray, Rushmore) make poor decisions that push them further away from where they want to be. Some, like Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro, The French Dispatch) attempt to bring attention to their problems by taking drastic measures rather than seeking help in a healthy way. Some deny, get angry, or bargain. Some combine it all together to attempt to move themselves on to something else.

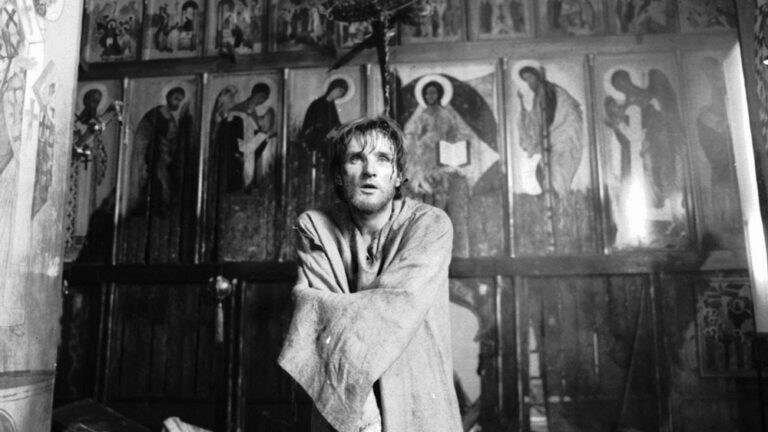

Francis Whitman (Owen Wilson, The Darjeeling Limited) is one of these people that combines a lot of feelings at once to try and combat his depression. While all the Whitman brothers are all definitely depressed, Francis is the brother who is the most desperately down. He plans a spiritual journey for his brothers to bring them closer together (denial). He wants this trip not only to bring them closer, but to unite them with their estranged mother (bargaining). When things don’t work out or when someone dispels the magic of the occasion, Francis lashes out (anger). He uses it all as a smokescreen for what’s truly going on with him.

It isn’t until the three brothers are doing their preflight rituals in the airport restroom that Francis finally lets down his guard. In the shot, the camera looks out as if it’s the mirror in the restroom, a shot Anderson chooses for many of his films. Francis pulls off his bandages to reveal the extent of the damage to his face from the motorcycle accident. As they survey the damage, Francis tells his brothers that the accident was intentional, that he crashed his bike in a suicide attempt. As the brothers look at him through the lens of the mirror, then in their physical dimension, they suddenly see Francis and this trip differently. Francis has always seemed like the rock of their group and now, they see his vulnerability and permeability. He’s brought down for them and for us. Not out of pity, but out of respect do they follow him from there.

Pity is also the last thing Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright, The French Dispatch) needs. He’s intelligent, witty, and verbose to name a few of his more excellent qualities. He just also happens to be gay and in the Andersonian universe that is a rare sight. There have been characters whose sexuality has been hinted at, Margot Tenenbaum (Gwyneth Paltrow, The Royal Tenenbaums) is seen in the arms of another woman, or Gustave (Ralph Fiennes, The Grand Budapest Hotel) who “goes to bed with all [his] friends,” which doesn’t deter, but encourages Dmitri (Adrien Brody) to even more vehemently hurl homophobic slurs his way. Then there’s Alistair Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum, The Life Aquatic), a character who is mocked, misunderstood, and maligned is often referred to as “half gay.” Yet, this is the first time in an Anderson film in which a gay character is allowed to define himself.

Unlike other gay characters, Roebuck Wright isn’t a tragic gay in the way of queer best friends through movie history. He is the mover of his own destiny and his depression from grief isn’t due to the fact that he’s gay, but in the fact that he can’t live the life he wants even if he’s honest about who he is. He tries to tamp that depression down through his work. It’s only his editor, Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray) who can see through the words and asks why he didn’t include the best part of the piece. Roebuck tosses it off as too sad. Arthur says he needs to include it.

The scene Roebuck removed is of himself sitting with the poisoned and now recovering Nescaffier (Stephen Park), who tells Roebuck of a taste he had in his mouth. For the chef, this taste was something otherworldly, beautiful, and fleeting because he tasted it in the depths of the poison he used to defeat the kidnappers. In that moment, Roebuck understands that his life, the life he wants for himself, is fleeting. Any happiness he experiences living authentically can be taken from him by the majority who looks down on him. Roebuck grieves the life he will never live and so he’s depressed underneath his erudite, confident exterior. He’s just a sad man in a cage being watched over by someone who knows his secret and despises him for it.

Everyone has guessed Richie’s (Luke Wilson, The Royal Tenenbaums) secret. He isn’t good at hiding his feelings for Margot in spite of his attempts. Richie’s been in love with Margot ever since he figured out what love is. It’s most evident as Margot gets off the bus to meet Richie and we see from Richie’s perspective the way he sees her as a gliding angel coming toward him. He has his own life and loves, but it’s Margot that affects his decisions and moods the most. She’s the reason he quit tennis and the reason he lives at sea. It’s his anger at the list of lovers she’s had, a compound, concrete fact of her dismissal of his feelings for her, that pushes him to his ultimate decision.

The scene of Richie in the bathroom when he decides to take his own life is one of Wes Anderson’s most devastating. Much like when Francis looks through the mirror to us when he describes his suicide attempt, Richie’s pale blue eyes gaze at us in silent determination. Anderson uses jump cuts to speed up the process as Richie clips off his hair, trims his beard, shaves his face, and uses his razor blade to slice into the veins in his arms. He stares at us as we realize what he’s done, then he looks down at the blood pouring out of him to see what he’s done to himself. The scene is wordless because Richie’s decision, his depression, and his determination are all present in his stone face.

Richie survives, but he isn’t miraculously happy to be on the other side. He’s still in a deep depression. It isn’t until Margot comes to see him and asks to see his stitches that Richie’s need to be free of his pain becomes truly evident. The stitches aren’t a single line down his arm, they aren’t a couple lines across his wrists, Richie cut deep and jagged lines all over his arms. He wanted this to work. He wanted so badly to not be in pain any more. Margot will never love Richie the way Richie loves Margot. By attempting to send Margot a message, Richie finds that his depression will continue until he finds a way to accept that he and Margot will never be. The hardest part of his grief is acceptance and not fighting against it as he has.

Those in a depression don’t always look sad, they don’t always act sad, they don’t always say sad things, listen to sad music, write sad poetry, or watch sad movies. This doesn’t change the fact that they have found a void within themselves. This void can’t be tamed by the sheer force of will, no matter how much we wish it could.. It can’t be tossed aside through righteous anger, denied with a fantasy land, or disappeared by bargaining our way out with the right amount of anything. Depression is the black cloud amongst Wes Anderson’s candy colored worlds. It lives with his characters like the grief they all carry. It’s how those characters deal with it that defines them.

Wes Anderson’s characters start sad and they stay sad, but as they stay sad, they accept that as a part of their lives. Their sadness, linked to their grief, is a starting point toward the next phase of their lives and typically toward the resolution of the film they’re in. They may stay sad, but their sadness is a little less having gone through something that changes the way they see the world. Like all of us who experience depression, the feelings never truly go away, but they ease. It’s a nuance of life and one that Anderson explores frequently, but uniquely in every film he makes. It makes his characters relatable even if they’re unrelated to most of our reality.