“Don’t Go To Film School, Or I’ll Hunt You Down With A Hatchet”: Harley Chamandy on Werner Herzog, Artistic Influences, and Self-Distributing His Breakout Indie, ‘Allen Sunshine’

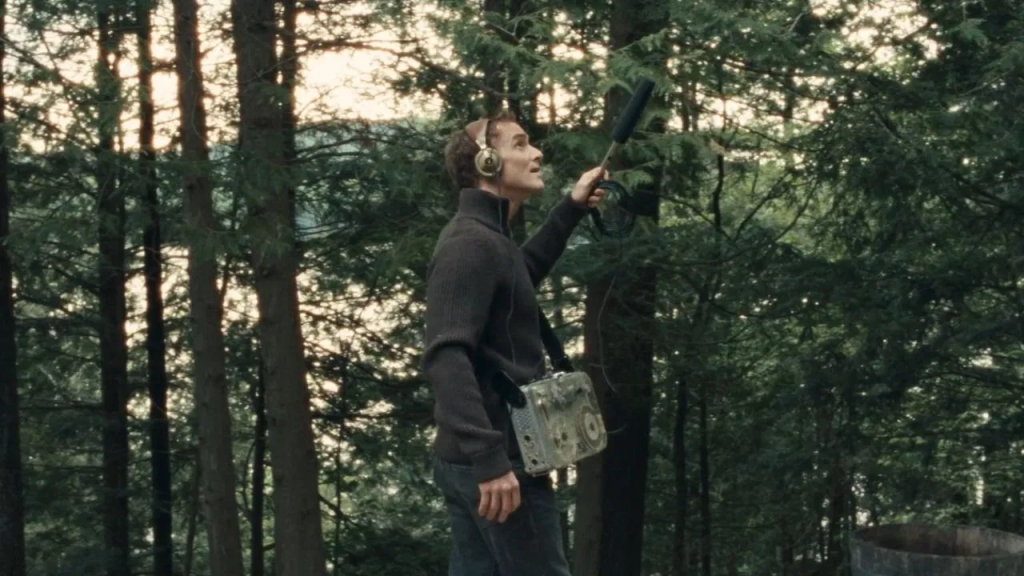

After 11 years in the filmmaking business, Harley Chamandy has yet to tire of the “grind,” as they say. Perhaps that’s because he only recently turned 25 and because the previous decade of work unfolded in the short film space until his feature debut – the 2024 gem Allen Sunshine is now available on VOD, and is screening at New York City’s Roxy Cinema on Friday, April 25th – was introduced to the world last year. Or maybe it’s because grind is all he knows as a first-time feature director who has handled the distribution and marketing of Allen Sunshine on his own. Even with the now-Oscar-winning Alex Coco (Anora) as an executive producer, getting Allen Sunshine in front of audiences fell (and still falls) on Chamandy’s shoulders. His hustle is only part of the reason this interview took place. The other? The film—which centers on a grieving music producer (Vincent Leclerc) who relocates to the Canadian woods to mourn and rediscover himself— is a special piece of work.

Chamandy first messaged me on X/Twitter within 24 hours of me logging his film on Letterboxd, thanking me for watching the film and offering his availability for a potential interview. He’s done the same with writers and editors at publications like Sight and Sound, The Guardian, and Paper Magazine, with each review helping the film’s visibility and each chat more illuminating than the last. My curiosity was piqued by his film and his methods, not least because he had won the 2024 Werner Herzog Film Prize after Allen Sunshine’s premiere at the Munich Film Festival. (Past winners include Chloe Zhao and Asghar Farhadi.) “Why on earth is this award-winning director reaching out to me directly?” I wondered. When we finally met over Zoom, I raised that fact to him straight up. He offered some insight, not just on his self-distribution efforts but also on his filmmaking influences, his plans for the future, and the Montreal-born filmmaker’s thoughts on how his home country has all but rejected his feature debut. Here are excerpts from our long chat, which have been edited for context and clarity.

Will Bjarnar: First of all, I love that you reached out directly to me. I think that’s really cool. Because while I learned about your film through coverage in outlets like The Film Stage [Allen Sunshine was included in their 2024 round-up lists of “The 50 Best 2024 Films You Might Have Missed” and “The Best Directorial Debuts of 2024”] and obviously soon saw the film, it was cool to have the director of a truly independent film showing how much they care about their work by reaching out to people that have seen the film.

Harley Chamandy: Sight and Sound took me, like, six months of [pushing for coverage]. At one point, [the S&S editor] was like, “Please stop.” And I was like, “Nah, I gotta make this happen.” I think [winning the 2024 Werner Herzog Film Prize] opened more doors, but I just wanted people to know about this thing. I think that this is something really important that I’ve learned as a young, emerging filmmaker. It’s more than just making a film. It’s being your own press. It’s the end of the era of the “mystical filmmaker,” like a young Terence Malick. That was a really cool thing, but it could never exist anymore. Society has changed, and so much is getting put out there; there’s so much noise. So, seeing that, I realized, “I’m going to have to do this all on my own. It’s gonna be a freaking grind.” And it is a grind. I just got a one-week theatrical release in Miami. I’m about to screen at the Roxy Cinema on April 25th in New York. I just really want people to see it in the cinema. I’ve been self-distributing, and it’s paid off.

Will Bjarnar: Well, let’s talk about that. When was the film officially released last year? I know it was at the Munich Film Festival first for its world premiere.

Harley Chamandy: Right, but we basically released it on November 12th on Apple TV+ and Amazon. Simultaneously, it was screening at Lincoln Center, the Angelika, the Curzon in London, a theater in Montreal, etc.

Will Bjarnar: So, you did all of those screenings, plus the release on VOD platforms. But now it’s going to the Roxy. You were just in France, and then in Miami… Is it just because you are self-distributing it that it’s had this untraditional rollout? Technically, it’s a 2024 release, but now we’re well into 2025, and it’s still getting programmed. That has to be exciting, to have it play wherever it can be played, no matter when it was released.

Harley Chamandy: Honestly, it’s just that people don’t know about it. This is the problem: Not to get on my high horse, but most people who watch the film like the film. It’s speaking to people, it’s crossing borders. I also showed it at a festival in Siberia that’s run by [two-time Palme d’Or-winning director] Emir Kusturica. They had like seven films in the whole festival, and they found mine somehow. It’s a good film, people just need to know about it. Truthfully, if I had someone like NEON or A24 pushing it out, it would be a whole other situation. But that’s just how the industry works, and that’s okay. You have to be patient. I’m also about to show it in Maine at “Space,” this arts museum kind of vibe, and then we’re going to Prince Edward Island, so it is, like, keeping the movie alive in a sense, you know?

Will Bjarnar: I think you touched on something really interesting there. In the current cinematic landscape, a new film could be coming out and getting coverage before anybody other than a very select few people have actually seen the movie. And then the movie comes out, there’s some more reporting on it being a big hit or something of that nature, and then after a week or two, it dies. Or, at least, a broad conversation about it goes dormant until we reach the end of the year. I say all of that to say that I think what you’re doing is important, and it can’t be easy, not least because of all of the travel it requires.

Harley Chamandy: Yeah, these are all great things, but they lead to burnout. I’m exhausted, but I have to keep grinding and getting the film out there. I wish more critics were able to write about the film. Maybe don’t quote me on who I was close to convincing. [He laughs; I comply.]

But one thing I would really love for you to quote is that I’ve gotten zero coverage in Canada. I’ve tried everything you can imagine, from reaching out to every single freakin’ critic, the Toronto [International] Film Festival, and everyone refuses to cover my film. Canada has zero support for a young Canadian filmmaker who has not only won the Werner Herzog Award but has also been on best-of lists, covered in Sight & Sound, etc. I can’t even get one review in the Globe & Mail. And to me, that’s the most frustrating thing.

Will Bjarnar: I remember seeing you tweet about that a while ago, but when I went back to look for the tweet so I could ask you about this specifically, I couldn’t find it.

Harley Chamandy: I probably deleted it. I don’t even care at this point. I’m gonna say how I feel, you know what I mean?

Will Bjarnar: Why do you think that has been the case with your lack of Canadian coverage? Honestly, I think there has been a gamut of excellent Canadian cinema in the last few years that goes beyond the David Cronenbergs of the world. In the last few months, we’ve seen Philippe Lesage’s Who By Fire and Kazik Radwanski’s Matt & Mara receive extensive coverage. I’m curious if you have an idea why your film hasn’t been given the same treatment.

Harley Chamandy: They’re a little more tapped in, for sure. Like, [Kazik Radwanski] is on like his fifth or sixth movie, and Philippe Lesage is Quebecois. That’s another thing: It’s very political. I’ll say it how it is; I don’t care at this point; I’m too far gone. But being an English-speaking person in Quebec is like having everything against you. They’re not going to support you. If your movie’s not French and if you’re not Quebecois, it’s not the vibe. Dude, I’ve been able to get a screening at Lincoln Center, and I can’t even get a local arthouse in Montreal. That, to me, is the most defeating thing. I feel like I’m kind of rambling, but it feels good to talk to you about this ’cause you’re a critic; you understand it’s a grind. I’m reaching out to you; that’s still a grind. But for Canada to not even be down to give me the time of day is extremely frustrating. Like, what other 22-year-old kid do you know that is getting awarded by his idol?

Will Bjarnar: Let’s talk about the Herzog connection. You won the Herzog Foundation prize last year, but long before that, you participated in his first-ever young filmmakers workshop when you were 17 and had started embarking on a filmmaking career even earlier. How has Herzog’s work influenced you in that journey? What did you learn from his workshop that has since influenced you?

Harley Chamandy: Well, just to make it super clear, I did his workshop when I was 17, and I completely lost contact with him after that. I just thought I was another student and that he would never remember my name. So, with the award, it seems like there was some tie-in, but you don’t understand: This guy wanted nothing to do with me. I tried to get his email, and he was like, “It’s time for you to move on, dude.” I tried to have that rapport, and he was just not into it. Honestly, I think that might have helped me grow as an artist. He actually said to me when I was 17, “You have to grow your own wings and fly. I’m just a guy here to give you a little bit of advice.” But I think the most important thing he said to me at the workshop was, “Don’t go to film school, or I’ll hunt you down with a hatchet.” I had just applied to film school, and I was like, “Fuck.” I called my mom and said, “We have to cancel the applications.” I ended up doing one semester at Pratt and absolutely hated it. I transferred to NYU to study global liberal arts, and I think what Herzog was really saying to me was, “You should be friends with someone like a butcher. You shouldn’t be around film people because you’re never going to be inspired by film people. You’re gonna be inspired by real life.” He told me to read classics, to learn a language, to go abroad.

Since I was a kid, I’ve always felt like I was making movies to compete with my idols, not to compete with a film student. I never felt like a film student. [Filmmaking] is just this natural thing, right? When I did win the Herzog award, someone asked me how I was able to deal with these heavy topics, and I didn’t know how to answer it because it’s always been something to me that has been more of a divine, secretive thing when I write a script. But Herzog answered for me and said, “You wouldn’t ask Mozart how he knows how to play the piano so young.” So, it’s inherent in you, that understanding, but then to hear Herzog saying it, it felt like I was truly being understood by a peer. My whole life, I’ve wanted to be at the level of the people I looked up to. This was the tap on my shoulder telling me that I was on the right track. It doesn’t mean I made it. It just means that I’ve trusted my gut long enough that now I’m on stage with the person who made me want to make films. He’s been so uncompromising and true to his voice for 60-plus years. He’s a singular artist.

Will Bjarnar: I mean, between Grizzly Man and Aguirre, the Wrath of God… Come on.

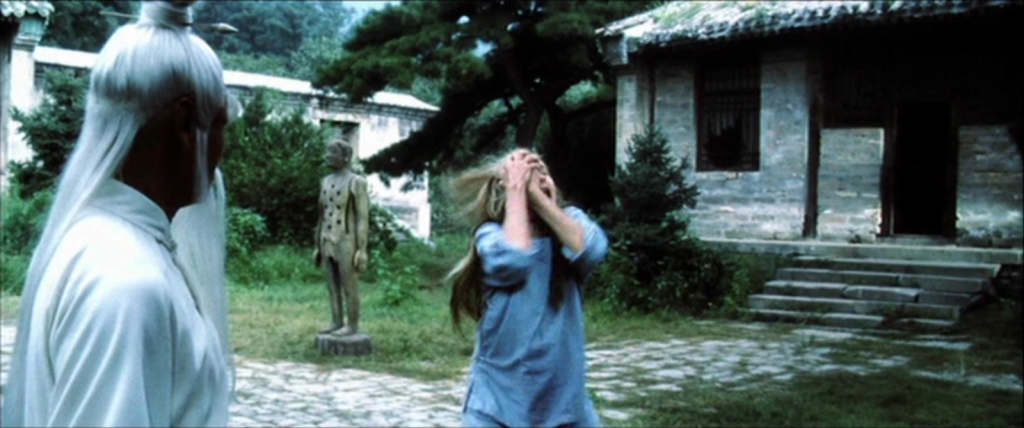

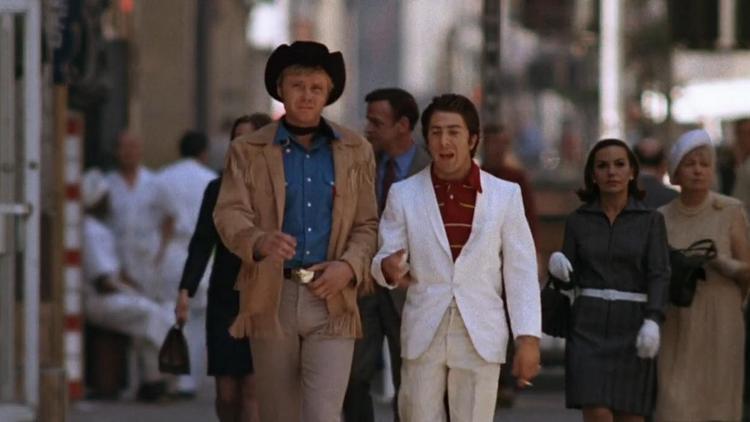

Harley Chamandy: I just thought of something. I think how it really all started was that I was really into fashion as a young kid. You know how kids have that stage where they dig Supreme and skating… Through that, I found Kids by Harmony Korine, and then through Harmony Korine, I found Werner Herzog. I think Herzog to me was the source for someone like Korine’s work.

Will Bjarnar: That’s fascinating because I don’t see those influences in your work. At least not in Allen Sunshine.

Harley Chamandy: Yeah, I’m not necessarily influenced by their films. I’m more influenced by any movies, honestly. I’m more influenced by painting, fashion, stuff like that… I actually wrote my college application essay on how the world had too many collage artists that everyone is taking from one another, and that’s why art is really uninteresting. I know you’re a critic, but I really believe that I wouldn’t be making films if I thought there were that many good films out there.

Will Bjarnar: Would you not classify yourself as a cinephile, then?

Harley Chamandy: I’ve never said that I’m a cinephile or anything, but I live for art and film. When I think of a cinephile, it’s too boxed in. To be a great artist, you have to be a file of the arts or whatever. I don’t know if there’s a word for that. But you have to see something in everything. That’s why I think there are so many lousy movies these days. It’s not just about the storytelling. It’s about what the characters are wearing, what the music sounds like, etc. To me, film is the most divine art form, and it seems like all these filmmakers don’t understand. They have this blank canvas, and they waste so much of it just trying to make some narrative movie. There’s so much more to film than that. I’m really frustrated by it. I don’t know how you feel, but I’ve left some bad reviews about movies that most people think are great. And now that my own film is getting a bit of press, people are saying, “How could you write such a bad review on a film?” But it’s just how I feel. Am I not allowed to have my opinion on how films should be?

What I tried to do with my film, and what I hope audiences do with it, is surrender to it and just be present with it. Someone came up to me after a screening once and said, “This film is very Buddhist.” I never thought of it that way, but I guess there’s something very meditative about it. Look, I love movies. I’ll watch anything from any country, but I always viewed filmmakers as artists, not as filmmakers. I don’t even like saying that I’m a filmmaker. I feel more like an artist who uses the medium.

Will Bjarnar: You said that you think about things like paintings and pictures. Is that, then, how you’re structuring your films? Are you thinking about the process through that lens, that you’re making a moving work of art with images that move as opposed to something still, like a painting?

Harley Chamandy: Oh, that’s interesting. Maybe the best way to answer that… Sometimes, I don’t even understand where something is coming from when I’m writing a script. I just love cinema and everything about film, but I guess I don’t actually love “technical” filmmaking. I do love filmmaking in terms of the actual process, but I’m not as excited talking about camera gear. I don’t care about that stuff as much.

Will Bjarnar: Your shorts are even more interesting to think about then. You made The Final Act of Joey Jumbar and Where It’s Beautiful When It Rains…

Harley Chamandy: There’s one in between that I removed offline. [Laughs.]

Will Bjarnar: Why is that?

Harley Chamandy: I was, like, 16. It was called The Maids Will Come On Monday. It was a family drama. At the time, I knew nothing about how short film festivals worked or anything. And I felt with Joey Jumbler, I gave it my all and didn’t get the results I wanted. And I thought maybe I had to follow more of a formula. I went against my gut and made a film that was trying to be commercial. It looks beautiful and all that, but it’s not really me.

Will Bjarnar: Aside from the obvious – the size of the crew, shoot duration, script, etc. – what are the key differences for you when you’re making a short versus an Allen Sunshine?

Harley Chamandy: Allen Sunshine is what I feel like I had to say. It felt like something that had been dormant in me for years, and I just never had the way to say it. I think it’s an accumulation of my aesthetic point of view of the world and also just my point of view of what and how a film should be. I think if I died tomorrow, I would die very happily knowing that I made a film I am 110 percent proud of. On the artistic level, I truly would not change anything. What I’ve learned is that the best method for me is keeping the people that you really love on your set. My girlfriend [Samantha Vocatura] does the costume designs; my mom [Chantal Chamandy] does producing and editing; one of my best friends, Kenny [Suleimanagich], shot the film. It’s a feeling having this energy where the people around you are excited about making great art. No one’s there for just another day at work. I think that’s really important. But to answer your question, I made Joey Jumbler at 17. What do I know yet? With Where It’s Beautiful When It Rains, I made a short film in three days because I really liked this child actor who was about to go on Broadway, so I wrote the script there and then, and we went out and had fun. That short was a reminder of why I love film. We went against all the rules: No permits, no crew, and it was just really exciting. The difference is that with Allen Sunshine, I was able to say what I really wanted to say in the film.

Will Bjarnar: Where did it come from, then? I know you had this image of a man on a boat in the middle of a lake. Was that all it took?

Harley Chamandy: I think that at the end of the day, no matter how you cut the cake, I view art as a sport. I think it’s very competitive. I want to be the best at what I do. I feel like that’s some Timothée Chalamet shit, but like, it’s really how I’ve always viewed it. I believe in objective good taste. And I think that the larger your toolbox is, the more you can inform yourself. And that’s why I’m so specific about what I think a good film is. I think that’s the accumulation of my toolbox, right? It’s a film where the image is at the forefront. The music plays such a strong role; the quiet, the delicate details like [the scene where] the little girl takes the bow out of her hair and puts it on a dog. That’s what I think makes great cinema. If you go back to all the work that I think is great work, that’s what these artists were doing. It’s a sensitivity that I feel is lacking in modern cinema. That’s something I’ve been chasing. The scene when [Allen] eats the pie, and the kids he’s with are doing magic tricks with a coin? These are all ideas. There are all these little things I want my films to have. I really want to push this agenda that all art comes from the same place, whether you’re a fashion designer, a poet, a musician, or a painter. I am really trying hard to make conceptual, modern art more welcoming to cinema because I think they exist in the same way, but society divides them in a sense.

Will Bjarnar: Another quote of yours from the past: You had the desire to “want to tell a story about love and friendships, and what it means to live with and without them. Thematically, that’s omnipresent in modern cinema, especially of the independent variety. You take that and broaden the scope of it while remaining intimate, crafting the story of a 40-something widower, and you’re only 25. How do you go about shaping that while writing the script? Are you working with your actors? Going off of life experiences, yours or others?

Harley Chamandy: It’s me alone. I am getting inspired by the music that I was listening to throughout and just trusting my gut. If you want to know how I really feel, it’s just that in every scene, I’m trying to make a fire scene, and somehow, it all kind of comes together. Like, that’s it. I’m not an intellectual. I’m not thinking about how the character feels. I’m just going with, “What’s the most fire thing he could say?” And I know it’s weird, and it’s the least obvious thing someone would tell you, but I’m writing it, and I’m like, “I want him to play chess now because I think it’s going to look great.” It also works on an emotional level because [Allen] can’t connect with a woman at that moment. But I’m not thinking about the emotional thing. I know it’s right, and I’m never doubting myself. And the minute I do doubt myself is the minute that I know it’s wrong. Here’s an example: In the film, you never see flashbacks. I actually wrote them at the last minute and put them in, and I shot them, but I never put them in the movie. I should have trusted my gut there because I wasted a whole day shooting flashbacks that I knew, deep down, were not right for this film. It’s a film about the now, about the present, and it didn’t matter if you ever saw [Allen’s late wife]. It’s just about his feeling in that moment.

Will Bjarnar: Who’s your therapist?

Harley Chamandy: I don’t have one. I’ve never been to therapy.

Will Bjarnar: Screw you. I had therapy at 8:45 this morning.

Harley Chamandy: Herzog says never go to therapy! It’s better that we never talk about the dark stuff of humanity.

Will Bjarnar: I think it’s impossible for you not to be thinking about the emotional, thoughtful side of it, though. It’s almost offensive that you’re not.

Harley Chamandy: Well, it’s a very deep thought. I do really love humanity, and I know that it’s a really hard thing to love, especially in the modern world. But I really believe that choosing optimism is choosing happiness. I think I learned that really early on. I read a book by this Vietnamese monk when I was in my junior year of college, and there’s one thing that stood out to me. He just says happiness is a habit. That clicked with me. I was like, “Fuck. Why is everyone chasing this shit? You can just convince yourself?” I feel like something happens [within you] where everything becomes beautiful. I’m trying to view everything in a beautiful way. Now I feel like you’re my therapist because I’m saying this out loud, and it’s kind of hitting me back, but I’ve never really been able to understand why I know these things.

Huh. That got deep.

Will Bjarnar: Let’s get deeper then. It’s ironic to ask because I know you didn’t necessarily like getting technical, but it’s important to do this. The film’s look and sound feel like narrative choices just as much as they are stylistic ones. Why are you inclined to make these choices, like shooting on 16mm film and sourcing synths for Allen‘s music production? Those are specificities that a great many films wouldn’t care to make.

Harley Chamandy: That’s literally where I think modern cinema has gone wrong. No one cares about that stuff much anymore. I really wanted to make a film that felt timeless. That was one of the biggest things for me. I wanted to make something where there wasn’t a time period where everything in it could exist 10 years from now or 10 years ago. I don’t want any of my films to be dated at any time because if a film is dated, for me, it loses emotional resonance. There aren’t any iPhones or computers. Even the clothes are all secondhand.

I really wanted to explore an artist that was making art for themselves. That’s a very rare thing that is not really portrayed in modern media. There is something really beautiful about the artist who just makes the work for themselves and is not thinking about the audience. And you know, that was always something for me. When I would go to Q&As and ask filmmakers something, I’d always ask the same question: “Do you think about the audience when you’re making a film?” I would always ask that because, to me, I figured that all these great artists would never think about the audience. Especially Lars von Trier; he was big for me. The same goes for Harmony Korine, Vincent Gallo, Michael Haneke, Abbas Kiarostami, etc.

Will Bjarnar: Would you say that’s how you approached this film?

Harley Chamandy: With this one, I was really trying to make a movie that I liked. But from now on, what I really want to do is go to Hollywood to make a film that can keep the same sensibilities but be more populist and have a broader fare. As in, “How could I make something like Allen Sunshine, but for the masses?

Will Bjarnar: I think Allen Sunshine should be something considered “for the masses,” if you will. For audiences who have seen it or are going to see it soon, what do you hope they take away from the film if there’s even one specific thing?

Harley Chamandy: Maybe if you learn to live like a child again, you can realize what really matters in life. Or, once you rediscover how to live again through the eyes of a child? I don’t know. Something like that. I don’t even know; honestly, there is probably nothing. Whatever you take from it, you take from it. I think the truth is that you have to stay curious, like a child, about the generosity of life. It opens up to you more, and you see things for what they are. So many kids these days are depressed and have so many issues. And I think that once they understand that having gratitude for the small things in life, like a conversation or having a piece of pie, that’s really what life’s about. It’s about playing with your dog, and everything else is extra.

Allen Sunshine screens at the Roxy Cinema in New York City on Friday, April 25. It is also available to rent on VOD.