Director: Barbara Kulcsar

Writer: Petra Biondina Volpe

Stars: Esther Gemsch, Stefan Kurt, Ueli Jäggi

Synopsis: A retired couple is getting ready to enjoy their life as pensioners on a cruise trip through the Mediterranean. The spouses end up going on separate journeys of self-discovery and finding unexpected ways of how to spend their golden years.

There is a certain tendency amongst particular groups to sneer at the “grey-rinse” comedy. Especially if that comedy is written about people of a certain middle-class and relatively affluent background. Barbara Kulcsar’s Golden Years is precisely the kind of film that will raise those hackles because a journey of self-(re)discovery for privileged white Swiss people is ultimately going to be read as unimportant fluff. What this reading elides is that we are all on the inevitable march towards death. Some of us are most certainly in a better position to cope with it than others, but it is coming, no matter what. It’s highly unlikely that Barbara Kulcsar and screenwriter Petra Biondina Volpe are making a film with universal appeal. However, they are making one with a particular appeal and charm.

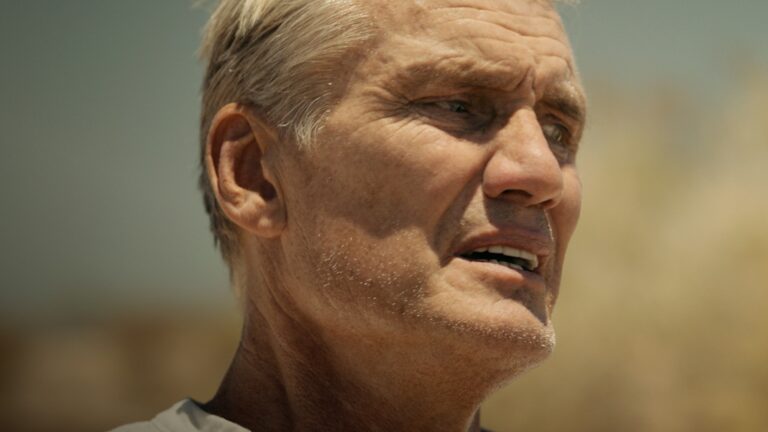

The film begins twice. In the first scene we see Alice (Esther Gemsch) grimacing in a dance class for seniors. The next scene is her husband, Peter (Stefan Kurt) at his low-key retirement party. He’s sixty-five and he can stop working. His job isn’t even going to be filled. He’s redundant in so many senses of the word. He steps outside and lets the red party balloon float off into the sky. Here’s to the “bright horizons” of his future.

Alice and Peter have been married for over forty years. They have two adult children, Susanne (Isabelle Barth) and Julian (Martin Vischer). Susanne is eyeing her parents’ large house for herself and her family as she has decided they don’t need all that space now they are old. Julian doesn’t want the house as he’s happy(ish) living a more bohemian permanently single life elsewhere. The siblings bicker perhaps more than their parents do. Yet, there is a sense that Alice and Peter have little in common except the familiarity of a pair of comfortable shoes.

Alice believes that now Peter finally has leisure time, and she is no longer bringing up a family, it’s the moment to reinvigorate their relationship. Whereas Peter really just wants to do nothing much at all. They both believe they’ve earned something from life and each other but what that actually is, neither can properly articulate.

The sudden exercise-related death of Alice’s best friend Magali (Elvira Plüss) puts them both into a form of crisis mode. Peter suddenly becomes a fitness fanatic and Alice discovers an entire life Magali was hiding from her milquetoast husband, Heinz (Ueli Jäggi). Magali had a secret lover named Claude in Toulouse for fifteen years. Peter’s goal is to extend his life (“What for?” Alice asks), and hers it to find something as passionate as whatever was going on between Magali and her once yearly lover.

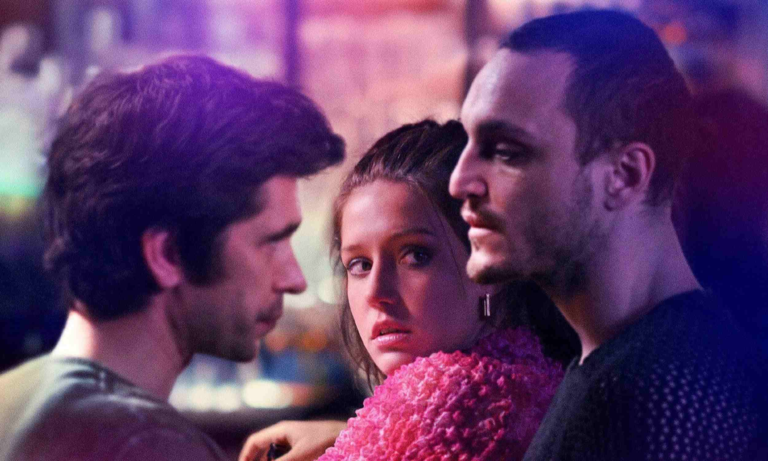

A cruise ship holiday through the Mediterranean crystallizes just how far apart they have drifted in love and life philosophy. Peter is more interested in early morning workouts with accidental third-wheel, Heinz, than he is in sex with Alice. Alice meets Michi (Gundi Ellert) a divorced woman from Basel who tells her that she finally feels free to do what she wants – her deliberate unfettering somewhat shocks Alice, but also intrigues her.

A luxury cruise might seem like the least auspicious place for a radical marriage breakdown – but in a way it makes perfect sense. Everyone on board is told to have “fun” – all their material needs are catered for. They just have to sit back and relax and enjoy the ride. So, Alice essentially jumps ship in Marseilles to go on her own journey which will eventually lead her to Toulouse where she can tell the mysterious Claude that Magali has passed away. Peter can’t believe Alice would ever do something that reckless without first consulting him and immediately flies into tantrums and panic-based hypochondria. Realizing he can’t get the ship to stay in port to find Alice (a real the world doesn’t stop just because you want it to moment for him), he eventually flies home with his new “wife” figure, Heinz.

Alice’s journey is very much her down the rabbit hole experience where she comes across a bunch of colorful characters. She meets some mushroom dosing grey nomads, buys new dresses because she just feels like it. Gets admired by men and women alike. Gets lost and found by a series of people. She finally reaches Claude and the revelation of who Claude actually is both shocks and satisfies her. It might not be at all shocking for the viewer, but for Alice and her quiet and restrained existence, it’s a rewiring of what she thought was possible in life.

On the home front, Peter moves into a cozy domesticity with Heinz. Essentially, he replaces Alice with a man who seems as uncomplicated, if a little morose. His daughter Susanne is having a nervous breakdown and is drinking too much and arguing in front of her kids who know what’s going on better than Peter does.

When Alice finally returns to her home she finds she doesn’t have one. Peter has thrown her out for leaving him on the cruise. Susanne doesn’t want to deal with her because she thinks Alice was selfish for leaving Peter. Only Julian has some sense of what is happening to his mother and takes her in, but even that won’t work with his Tinder Hook-up lifestyle. At some point, everyone is going to have to sit down and work stuff out.

There is of course a whiff of “first world boomer problems” in the film. Yet, the humor and general good-naturedness of the film mostly overcomes its flaws. Barbara Kulcsar is pointing out that love and working out life is difficult for every generation. No one is truly settled and sorted out as long as they’re alive. Their levels of fiscal ease may vary; but when one is looking at the so called “last stretch of life” in their sixties, Mary Oliver’s poetic question “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” comes into play.

Golden Years is breezy, silly, and often frustrating. It commits to its more serious themes through comedy and sometimes that lets it down. Barbara Kulcsar’s “senior comedy” does have enough unpretentious pathos to allow the audience to connect with characters who seem insufferable. As Mary Oliver wrote, “Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?”