What makes a film timeless is truly within the eye of the beholder. Many look back to the dawn of cinema and the birth of Hollywood with films like The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, or It Happened One Night. Others prefer to think about spectacle and technological innovation – so films such as Ben-Hur, Lawrence of Arabia, or even Titanic may come to mind. And while there is merit in both of those ways of thinking, I have always been drawn to stories and themes – particularly those films that hold up and make a bigger statement decades after they were released. Mike Nichols’ debut feature, The Graduate, is a film that will always feel here and now because people will forever and always wonder what the correct path forward is for them. James L. Brooks uses humor to disarm us and explain content creation in Broadcast News – a film all about integrity, authenticity, and what drives the viewer’s attention. More recently, Parasite and the way in which it navigates class and social status within the thriller genre will make it one of the most timeless films to win Best Picture. In this spirit, I turn to Safe, Todd Haynes’ chilling 1995 film, which explores a distinctly modern form of illness: fear and alienation in an overwhelming world.

For the sake of context, what links all those films I mentioned in the previous paragraph is that I have seen them all multiple times. But what happens when someone watches a film for the first time since it was released 30 years ago? Will the viewer feel an emotional distance from the characters and storylines because of the dated nature of the events and how they unfold? Or, on the flipside, will the relevancy of the subjects and themes being examined hold up and be exemplified because of how timely they are? These questions frame my experience with Safe, a film I watched in full for the first time thirty years after its debut – and one that remains hauntingly prescient.

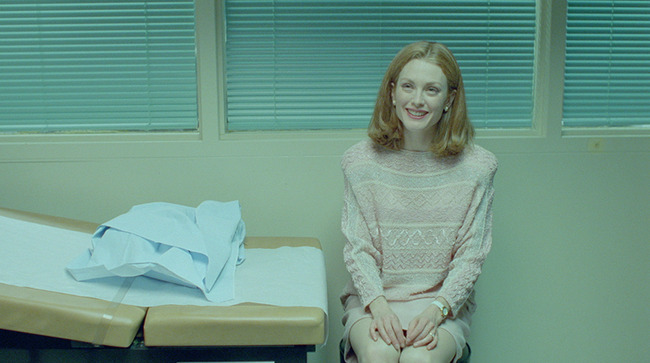

Let’s begin with the world of Safe as it first presents itself. Carol White (Julianne Moore) is a self-proclaimed homemaker living in the San Fernando Valley in 1987. Her husband, Greg (Xander Berkley), clearly makes an ungodly amount of money, as they live in a gorgeous house filled with lavish décor and expensive furniture. Carol spends her days doing aerobics to killer ‘80s tunes, going to lunches, and consuming vast quantities of milk. But recently, Carol has not been feeling well – suffering from long coughing fits, moments of lightheadedness, and even nosebleeds. Naturally, she visits the doctor who, quite quickly, gives her a clean bill of health. This disconnect – the contrast between Carol’s environment and her unexplained suffering – sets the stage for the film’s central question: What is happening to Carol? And more importantly, why is no one taking her seriously? As Carol searches for answers in a world that insists she is fine, her attention is caught by a flyer with a simple but ominous question.

“Do you smell FUMES?” The film shows that Carol has had a difficult time navigating the busy Los Angeles roads and all the exhaust being pumped into the air. An idea is planted in her brain that only fully grows into action after two health related incidents: one at a baby shower and one while she is being tested for allergies. Eventually, Carol ends up at Wrenwood, a place where people who are also allergic to the 20th century go for rehabilitation and spiritual awakening.

SAFE ROOMS & COVID

I was 8 years old when Safe was released theatrically in 1995. There is no way I would have understood what was happening to Carol, who Todd Haynes and Julianne Moore were, or how this film was commenting on people’s reactions to illnesses they do not understand. Ironically enough, I was born the year that this movie starts: 1987. Ronald Reagan is firmly in his second term and the country is trying to navigate its collective feelings towards the rise in AIDS and HIV. These unknown ailments confounded doctors and laypeople alike, but, as a society, the reaction to those diagnosed was distance – “do not come near me!” Gossip, misinformation, and innuendo commonly flew across dinner tables and cocktail parties; particularly, the idea that AIDS and HIV were only targeting gay and lower-income groups. This historical backdrop adds weight to Haynes’ choice of protagonist in Safe, a film that subtly shifts the frame of illness from marginalized bodies to privileged ones—without erasing the original context.

What makes Haynes’ approach to Safe so unique and inviting is that it both focuses this new, unknown, 21st century disease on an affluent, straight, white women while never ignoring that AIDS and HIV exist. This is not a story about someone in a low socio-economic class or in a frequently marginalized group: it is about the ones who gossip. Decades later, the film’s resonance has only deepened, particularly considering another recent health crisis.

Watching Safe in a post-COVID world reframes the entire viewing experience. Had I seen this movie for the first time in 2019, my mind would have made the connections to HIV and how society reacts to the unknown, but the personal connection would not have been there. Context is key: how and when a movie is seen can greatly shape the experience. When I see Carol walking around with an oxygen tank or people at Wrenwood wearing masks, I do not think that this seems odd or foreign: I relate to it. Instead of having safe rooms built in our homes, people just stayed home. Friends and family with previous conditions were isolated in dens or guest rooms, people sprayed and cleaned items that were delivered from grocery stores, and millions questioned whether vaccines would help or harm us.

Carol is even more knowable as a certain type of person who lived through COVID-19 as she continues to attempt her previous routine despite her being immunocompromised. As a voiceover explains the benefits of fasting, safe diets, oxygen tanks, and “unloading,” Carol still gets in her car and drives to the dry cleaners – a place of business that is completely built on the use of chemicals. Her extremely physical reaction to this place currently being sprayed for bugs is scary and traumatizing, and yet I cannot help but wonder why she would go there after all this newfound information she has acquired? The answer lies in appearance. Maintaining her perfect, white, upper-class lifestyle is part of the illness itself. It is not just chemicals that are poisoning Carol – it is the pressure to remain a pristine, passive figure in a world that does not believe her pain is real. To understand Carol’s choices – especially her resistance to change – let’s examine the cultural context she inhabits: the fads, habits, and affluence that define her world.

FADS & AFFLUENCY

Pop culture and social media have made our awareness of new dietary supplements, workout styles, and medicinal weight-loss treatments as high as they have ever been. But even before the 21st century, new fads would still find their way from one location to another. Setting Safe within sunny California and the Reagan-era 1980s puts us in a rather unique time and place. Fruit diets and aerobics to pop music were standard, particularly with those with free time during the day. Without spelling it out, Haynes does a great job of simply showing us who is going to these fitness clubs: bored, rich, white ladies with their husband’s money and nothing to do. Yes, it is an oversimplification, but it is also Carol’s reality. And it is through her eyes that the viewer experiences this world. But Carol’s privilege also prompts an important question for us and for the film.

Early on, I found myself wondering if I should care about Carol. This is not because I think Carol is a bad human being or that she has actively done anything to make me feel uneasy about her, but more because of her status. To some, daily problems that exist are “Do we have enough money for the electric bill this month?” or “How am I picking up my child today?” For Carol, her day-to-day problems seem like non-issues: the wrong color couch being delivered and deliberating over getting the fruit salad. It is easy to dismiss characters like Carol, to let the “affluency wall” keep us at an emotional distance. But Safe carefully dismantles that wall. By placing us alongside Carol as her body begins to fail her, the film demands empathy – and reveals that even the seemingly untouchable can unravel. And no one helps build that empathy more than Julianne Moore.

The way Julianna Moore uses her eyes in this film is exquisite. There are moments where Carol has completely zoned out mentally and is no longer listening to what is being said. This is exemplified at the business dinner with the vibrator joke. There are also scenes where Carol recognizes that something is wrong with her and her eyes go wide: the nosebleed while getting her hair done and the struggle to breathe at the baby shower stand out. Carol is not a character of action; she reacts – and because of this the confusion rises. That emotional mirroring is what makes her illness so frightening: the viewer experiences it alongside her.

When that emotionality is not set up correctly, I find it difficult to empathize with characters who are wealthy and dealing with problems foreign to the majority of us. Films like Call Me by Your Name or Frances Ha challenge me – not because they are poorly made, but because their protagonists come from privilege and have support systems that shield them from real consequences. The “affluency wall” I build up feels insurmountable and I cannot connect with them. To me their issues seem solvable, they are not alone, and inevitably they will succeed and prosper.

But Safe does something different. My initial hesitations with Carol disappear when she collapses to the ground and starts bleeding at the dry cleaners only to be told that there is nothing medically wrong with her. And that is it – I am fully invested. The movie, slowly and deliberately constructed by Haynes, introduces you to Carol, her wealth and status, and trepidatiously gives you clues to her being unwell. Is it a sickness? Is it a mental disorder? I do not know and it makes me just as frustrated as Carol is when she is told that she is fine. When she tells her psychiatrist that she has been under a lot of stress, you may ask yourself as I did “what stress?” There does not seem to be anything weighing too heavily on her mind until these symptoms begin to manifest physically. And it is not just her privilege that isolates her – it is how society responds to her perceived fragility. Race also plays a pivotal role in how Carol’s illness and her identity are framed.

RACE & MILK

Carol’s admission to Wrenwood connects us back to her position in life: someone able to afford this treatment. Rehabilitation facilities and rejuvenation clinics are not cheap – usually not options for most people. Just as significant is Carol’s racial privilege. Carol’s family, friends, and most of the people she interacts within the film are white – another interesting and provocative choice by Haynes. This racial homogeneity becomes even more pointed through one recurring motif: milk. Milk functions in the film as more than a beverage – it becomes a visual metaphor, loaded with cultural and racial meaning.

When I think of milk, my mind is transported back to 1995 and the “got milk?” campaign. As a child, you grow up learning that milk helps with calcium deficiencies and that it “does a body good.” In its own unique way, milk is medicinal. However, the pure white color of milk makes it a perfect choice of beverage for Carol. It is as if she takes her daily dose of “Caucasicillin” to remain in the world she has married into. Milk and its racial connotations have been put on screen successfully in Jordan Peele’s Get Out in which Allison Williams’ character does not mix her colored Fruit Loops with her white milk. This moment of visual racism in Get Out is very brief and the film goes on to show us other provocative images, but Safe lingers in the metaphor. For Carol, milk is not nourishing – it is toxic.

During a hospital visit the doctor says “Well…hmm. I really do not see anything wrong with you, Carol. I mean, outside of a slight rash and congestion.” Carol responds to the doctor’s questions about drugs by saying that she does not partake and that she rarely even has coffee. In fact, she states, “I’m just a total milkaholic actually.” The doctor replies, “Well stop the fruit diet. You need protein. And while you’re at it…try staying off dairy. Dairy’svery hard on your digestion, hard on your intestines.” Making Carol give up her one real source of sustenance is also her having to give up something that makes her white and powerful. Milk is also what her body rejects when she hugs Greg the morning after their fight in the bedroom – her body is telling her that all this white privilege needs to be examined more thoroughly.

One of the most visceral scenes in the film occurs during Carol’s allergy test. She believes that these tests will fix her and let her go back to milk and her Caucasian filled world, but the doctor explains that these tests are merely performed to help guide you to a new path – one in which these harsh reactions do not occur. While being tested for milk specifically, Carol’s heart rate increases and her breathing becomes short. Milk is the link between her social class and her physical ailments. It’s a terrifying moment that makes the metaphor literal: her body is rejecting whiteness. Like the doctor explains – “We can turn it on and off like a switch. We just do not know how to make it go away.” But Haynes does not stop there. He complicates the racial critique by inserting one of the film’s most pointed, uncomfortable moments.

To fully unpack the film’s racial commentary, I must bring up Rory’s (Chauncey Leopardi) essay on gang violence. At the dinner table, he reads aloud a report dripping with racist generalizations about Black and Chicano communities.

RORY: “In the 80s, there are more and more gangs in the Los Angeles basin, plus many more stabbings and shootings by AK-47s, Uzis and MAC-10s, killing numerous innocent people. L.A. was the gang capital of America. Rapes, riots, shooting innocent people, slashing throats, arms and legs being dissected were all common sight in the black ghettos of L.A. Today, black and Chicano gangs are coming into the valleys in mostly white areas more and more. That’s why gangs in L.A. are a big American issue. Rory White.”

Rather than questioning his language or assumptions, Greg applauds him: “Good job, Ror.” And while Carol wishes the piece was not so gory, she does not seem to think it is inappropriate either. This dinner scene mirrors the public discourse of the era, where fear of the “other” – whether related to AIDS, crime, or urban decay – was comfortably embedded in polite white society. Meanwhile, the family benefits from these same systems: they enjoy wealth, safety, and domestic help from a Latina maid. This hypocrisy is not incidental – it is central to Carol’s unraveling. Wrenwood may offer physical isolation from pollution, but it also represents a withdrawal from the uncomfortable truths of the world Carol belongs to. This 21st century disease is not just about fumes and chemicals, but the actual world being presented to us on the news and in the media.

And perhaps that is why her last name is White. It is not just a surname – it is a symbol, a diagnosis, and a warning.

CONNECTION & LESTER

From the moment Greg is first seen in the film, I have doubts regarding his sincerity and the longevity of their marriage. Some of this comes from my connection to Xander Berkley and the roles he has played in other films. When you play Waingro in L.A. Takedown (and Ralph in Heat), double-crossing Agent Gibbs in Air Force One, and a slew of other crooked cops and less-than-reputable characters, chances are I will not believe your character’s integrity. But thanks to Hayne’s writing and Berkley’s performance, Greg becomes a fascinating character to examine. The first real interaction between Greg and Carol is when they are having sex after arriving home. It is clear from Carol’s wandering eyes that this act is purely about Greg and his pleasure – about the housewife maintaining the status quo of a healthy and loving marriage.

Once Greg and Carol leave the uncomfortable business dinner, it becomes clear that Greg’s motives for Carol’s well-being are more selfish than pure. Greg is concerned with the appearance of a good marriage; the appearance of connection. Greg wants what he wants and Carol’s issues can be brushed to the side: this egotism is on full display in the scene in their bedroom immediately following Carol’s nosebleed at the hair salon. Greg compliments her hair and calls it sexy, but Carol states that her head still hurts – to which Greg responds with the very male “Nobody has a fucking headache every night of the fucking week.” Greg wants physical connection and he wants it on his time. When Carol proceeds with an explanation, Greg states “I don’t want to hear about it.” The cracks in their marriage only widen as Carol seeks out help—and is met with silence, avoidance, or worse.

When a psychiatrist is recommended, both Carol and Greg are hesitant. Even as late as the 1980s, seeing a shrink implied that the person going had real issues and could potentially be a dangerous person. Greg even starts to create more distance between him and Carol by asking fewer questions and engaging less in conversation. Eventually, Carol visits the psychiatrist and some interesting details about her are revealed. Haynes skillfully waits to reveal to us that Carol is not Rory’s mother – she is in fact the step-mother. When Rory leaves for school, he calls her mom, but it is slowly disseminated that the relation is not by blood. This lack of a true paternal connection to Rory is yet another way in which Carol’s focus on aesthetics is built on an untrue foundation.

Carol feels true connection when she attends her first meeting with a room full of strangers who are experiencing the same symptoms as she is. The man on the video cassette repeats the phrase “you are not alone” – planting the seed that what Carol needs is a connection to those with similar side effects to the 20th century. “What you most likely are is one of a vastly growing number of people who suffer from environmental illness.” Once Carol hears this diagnosis, she can proceed with treatments – but these treatments, while beginning a new connection, severs the connection with her old world. Greg cannot understand why she would go to this meeting or that these chemicals could be doing harm to her. That growing divide becomes literal as Carol builds a safe room and ultimately leaves for Wrenwood.

The disconnection between Carol and Greg becomes physical. First, she isolates in the safe room at home. Then, she leaves entirely – going to the Wrenwood facility in New Mexico. It is hard to determine if Greg truly cares about Carol. He is frustrated with her behavior and yet he comes with her to these meetings. However, Greg does not accompany Carol to Wrenwood when she first leaves – she is forced to fly by herself and take a taxi. When Carol calls Greg after she first arrives, he and Rory are clearly about to go have dinner. Greg repeatedly tells her to get well soon and that he will come visit once he hits his deadline. In an implicit way, Greg has already severed his connection with Carol and his visit to Wrenwood with Rory is more of a formality than genuine, caring visit.

During their visit, the emotional chasm between them is impossible to ignore. Rory walks away from them and is hostile towards Carol. Greg and Rory move Carol’s possessions into the igloo and Rory snaps back at Carol – Greg still refers to Carol as Rory’s mother. Greg walks next to Carol as she trips on a rock and barely has the strength to stay standing. Greg catches her but she must remove herself from him believing that his cologne could be why she is weak at that moment. Despite Greg saying he is not wearing any, his response is that they need to get going so they can catch the plane. The physical distance between them is noticeable and Greg even needs to ask if he can hug her before leaving. As the car drives off, it is clear that he is not coming back.

“Is that Lester you’re watching?” Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman) asks Carol this after she concludes with her V.O. letter to Greg and Rory – and the introduction of one of the smallest (but most iconic) characters in this film. Lester skulks by with his red shoes and ski mask – completely covered by clothing.

PETER: Oh, poor Lester. He’s just very, very afraid. Afraid to eat, afraid to breathe.

Peter quickly turns the topic away from Lester and back to Carol, but I keep wondering who this person is. Lester lives on the edges of a facility that is already on the periphery. Lester is the outlier of outliers, and yet feels like those people I knew during the COVID-19 scare – who even after the vaccines and all clear were lost and afraid to reenter society. Lester is seen only one other time in the film: Carol spots him during the group therapy session. Lester, donning the same outfit as before, is at a distance and behind a fence – still on the periphery. He tiptoes along, stealthily making his way through the desert brush – possibly the only one improving. Lester’s haunting vagueness leads us back to the film’s larger questions – about surface vs. substance and what it really means to be safe.

AESTHETICS & STRUCTURE

If you were to Google the word aesthetic, what would appear as your result would be “concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty” (or it would be if you searched on April 8, 2025 at 8:27 am EST). I personally love that the word “concerned” appears in the definition of aesthetic because it implies the importance of the exterior without much care for the interior. Aesthetics can be highly juxtaposed when comparing the outer beauty of something to a weak foundation or core. Take the actual start of Safe: aesthetically, the sparkling Mercedes-Benz hood ornament is seen gliding through a beautiful neighborhood full of nice houses and manicured lawns, but the score composed by Ed Tomney evokes a sinister tone and an underlying feeling that something is wrong beneath the surface.

Aesthetics without structure are just decoration. Form is needed for content to make sense. In the light of day after the opening few minutes, houses in Carol and Greg’s neighborhood are being built and in their unbeautiful state: wooden beams with no walls, exposed wiring, frames with no doors. A home is a blank slate until a person or people come in to give it purpose. For Carol, the aesthetics of her home (and by extension herself and her family) are of vital importance with no real acknowledgement of the foundation that makes it possible. Carol, in her garden, shows not so much an interest in horticulture but rather as a beacon of power and status. Similar images come across in another film about white, suburban issues in Sam Mendes’ American Beauty. This fixation with appearances becomes painfully literal when the wrong color couch is delivered.

Few scenes in the film capture Carol’s aesthetic anxiety better than the couch delivery. New furniture, silly though it may be, should be a joyous moment. Couches, tables, appliances: these are not cheap items and those of us not bathed in disposable income must work for and save to acquire them. It is only after a vigorous workout session to Madonna’s “Lucky Star” and an awkward encounter with her friend (who is also more focused on the exterior beauty of her home then what is happening to her emotionally surrounding her brother’s death) that she notices the color of the couch is not what she ordered. This scene has so many layers: one being that she did not stay to double check that the couch was what she ordered, another being that the couch that was delivered was black (playing against her last name of “White” and reinforcing this idea of “blacks invading white neighborhoods”), and lastly that Fulvia (Martha Velez) cannot see the problem with these gorgeous new couches in this space. It all reinforces just how rotten and decayed the foundation of Carol’s aesthetically beautiful life really is.

Another moment of improving aesthetics to mask deeper issues occurs when Carol goes to get her hair done. Billy Ocean’s “Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car” is easing us into the salon chair and Carol decides that she will not be getting her normal cut and instead will be getting a perm. Carol believes that yet another superficial change to her world may penetrate deeper and cure her ills. Chemicals rain down on her head and nail polish is applied –an aesthetically complete woman – but before Carol can leave her unstable core expresses itself outwardly and she begins to have a nosebleed. This moment epitomizes just how internally bereft and broken Carol is and that no amount of external tinkering can fix her. These illusions of improvement follow Carol all the way to Wrenwood – but even this place of healing is steeped in aesthetics.

As Carol approaches Wrenwood in her taxi, the ominous score heard at the beginning of the film kicks back in. Linking the music to these two moments of arrival creates a tension for the audience: why does the music sound so sinister if Carol is going to a place to help her heal? One reason could be that Wrenwood is also about aesthetics and less focused on the beliefs it touts in its promotional materials. Outdoor yoga, beautiful mountain vistas, and group therapy sessions are all available to Carol, but are they meant to cure her and fix the foundation of her physical health or are they options to simply mask and dull the pain and experience of the 20th century?

Enter Peter Dunning, the founder of Wrenwood. He speaks to the Wrenwood residents about seeing the world with love and all of the mandates they will need to follow while on the grounds. He also states Wrenwood’s mantra that includes the title of the film: “We are one with the power that created us. We are safe and all is well in our world.” Notice that he does not reinforce THE world, but OUR world – the world that is Wrenwood. At this point how effective the treatments at Wrenwood are is unknown – is this simply a place for people to escape their real-world problems? Peter presents himself as this charismatic and sympathetic man, but many circumstances within the film lead to an alternate reading of his character.

After first meeting Lester, Peter attempts to connect with Carol – and explain that her symptoms and reactions to Wrenwood are common. He uses his advanced, new age vocabulary to talk atCarol, not to her – he is not interested in connecting with her. During this conversation, she apologizes for not knowing what is wrong with her and her unawareness of how to move forward. And, in a very small, fleeting moment when Greg and Rory visit Carol, Peter’s house on the hill – separate from the rest of the community – comes into focus. To call it a mansion is both accurate and an understatement. One look at that house and it is clear that aesthetically it is gorgeous and well maintained, but at its core one wonders if the money from all the Wrenwood patients paid for it. Is Peter genuine in his pursuit of treatment or does he just talk a big game?

Claire (Kate McGregor-Stewart), one of the senior members of Wrenwood, tells Carol about her initial days at the facility and how she was scared and stayed mostly in her safe room. Claire explains that she used to look at herself in the mirror and repeat “Claire, I love you. I really love you.” Eventually this helped heal Claire and was a gift moving forward. During her time at Wrenwood, Carol witnesses Nell’s husband, Harry, pass away and discovers that he was staying in a unique room at the treatment center. Claire believes that Carol may be “spiraling down” and that she could benefit from staying in his old safe house – an igloo, a controllable space. “It’s ventilated and porcelain lined and he was perfectly safe as long as no one set foot inside.” And this will become the landing spot for Carol – safe, yes, but cut off from everyone. It is yet another aesthetically pleasing space, but structurally only continues to keep Carol away from society.

Our final image of the film comes after a moment of jubilation for Carol. Upon entering the igloo she folds her sweater, inhales some oxygen, and sees herself in the mirror. Carol approaches the mirror and speakers to herself in a fourth wall break: “I love you. I really love you. I love you.” And then silence…and then blackout. Her slight smile fades in the almost darkness as she tries Claire’s method of healing, but instead of feeling hope for Carol an ominous vibe settles in the air; a sense of doubt that Carol may only be safe at Wrenwood. And yet, it is precisely this doubt – the emotional silence beneath all the surface noise—that makes Haynes and Moore such a compelling team.

HAYNES & MOORE

Todd Haynes and Julianne Moore have collaborated on four of his nine narrative feature films, starting with Safe. Moving forward, Julianne Moore would emerge as one of America’s most reliable and committed actresses appearing in The Lost World: Jurassic Park, taking over the role of Clarice Starling in Hannibal, and working with Paul Thomas Anderson on both Boogie Nights (for which she would receive for first Academy Awards nomination) and Magnolia, among many other films. But in 2002, she and Haynes reunited for a film that feels like a spiritual sister to Safe: Far From Heaven. Though set in the 1950s, Far From Heaven echoes many of the questions Safe raises about performance, privilege, and repression.

Far From Heaven takes place during the idyllic 1950s in Hartford, Connecticut. Moore plays Cathy, a woman with many similarities to Carol in Safe. Both women are affluent housewives whose husbands are the breadwinners of the family; both women are interested in modern day causes and beliefs that are looked down upon by those in their communities; and both names are 5 letters and start with “C.” Despite all these similarities, from an acting perspective it appears that Cathy in Far From Heaven has more to react to. In Safe, Carol is the agent of change within the film. Cathy, on the other end of the spectrum, is reacting to the world around her and what her supporting characters are bringing to her. Cathy is married to Frank (in a Mt. Rushmore performance by Dennis Quaid) who is battling internally with being gay in a period where it was extremely taboo. Cathy also befriends Raymond (Dennis Haysbert), a Blackgardener in the community with whom she becomes friends. These two closest relationships in Cathy’s life become the source of gossip and innuendo within this wholesome, white community.

On the surface, Cathy’s problems are more accessible and easier to relate to than what Carol is dealing with. The film never specifies what Carol’s afflictions are or if she can get better. Cathy’s issues are on the surface: how do I support my husband without losing my family and can I have a friendship with a Blackman without staining my reputation? And while both Cathy and Carol are dealing with internal and external obstacles, Cathy’s are more personal and hidden – Carol’s are on the surface and rooted in the people surrounding her. It is not surprising that Moore earned a Leading Actress Oscar nomination for this film: dealing with a “taboo” issue during the prosperous ‘50s and having to react to everything happening to her. The role on paper demands a committed performer – one who is willing to constantly fail at obtaining her objectives. While Safe makes us work harder to figure out the world in which Cathy exists, Far From Heaven, while still challenging in terms of its themes, is easier for audiences to understand and empathize with.

It would take 15 years before Haynes and Moore would reunite on a film – this time in 2017’s Wonderstruck. Haynes and Moore find themselves at unique spots in their careers: Moore coming off a Best Actress win at the Oscars for Still Alice and Haynes with a critically acclaimed and multi-Oscar nominated film: Carol. While the core ideas underneath the surface Wonderstruck are unique and worthy of being evaluated, it feels like the film painted with too broad a brush and never fully investigated the heart of the narrative. The interconnectedness of the characters’ deafness and blood relation feels more coincidental than fully earned. Haynes makes some interesting stylistic decisions with the diorama feel towards the end of the movie, but it also feels less like a Todd Haynes film. The satire and nuance usually attributed to his films feels removed, and so does Moore’s star power. She plays two parts in the film: young Rose’s mother, Lillian, and the older version of Rose – but is underutilized in the film. For Moore and Haynes, it feels as if their artistic souls were not fully into the project. Moore’s presence feels more like a gesture of loyalty than a fully engaged performance. Haynes, too, seems restrained, directing a film that feels more studio-friendly than personal. But their next collaboration would return them to thornier territory – and spark critical discussion: May December.

Released on Netflix in 2023 and set in 2015, May December follows Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), an actress who is researching a role for an upcoming independent film. The wrinkle is that she is about to play Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Moore), a real person who when she was 36 began an intimate, loving relationship with a 7th grader named Joe (Charles Melton). The edge lacking in Wonderstruck is overcompensated for in May December: the overly dramatic score, art imitating life imitating art, living in a world you are not accepted in. This is not new territory for Haynes and Moore as this movie feels linked to Far From Heaven. The big difference here is that Far From Heaven came out in 2002 and examined the lifestyles and cultural norms of 1958 – May December was released in 2023, set in 2015, and is clearly commenting on the Mary Kay Letourneau scandal from 1996. Maybe the 44 years between film release and film setting in Far From Heaven just reads different from the timelines in May December and maybe in another 20 years I will look back and think that May December really had powerful insight, but right now I think this film feels too modern and too heavy handed.

And I can see why Julianne Moore would want to do this part. Elizabeth alludes to this in the film when she is doing a Q & A with high school students: playing morally gray characters is a fun challenge for the actor. Moore made some big choices with Gracie, with nothing more noticeable than the lisp. Moore is a dedicated actor and stuck with this choice from start to finish, but part of me wonders if this was done to show Gracie’s arrested development and naivety or if it was just planted as something for Elizabeth to copy at the end of the film when she is making the movie on Gracie’s life. May December is a film about performance copying reality, and Moore’s acting choices blur those lines even further. Whether it works may depend on the viewer’s tolerance for ambiguity and discomfort—but it is undeniably brave. And that lingering discomfort – between control and chaos, healing and illusion – brings us back to Safe, and the question that hovers over the entire film.

SAFE & UNSAFE

One of the most quietly devastating questions Safe asks is: Can one ever truly be safe? Everyone has a personal and unique definition of what that means. For some, safety can be as little as steady income and a roof over the heads of yourself and your family. For others, safety is iron gates and security systems and multiple firearms. Even these two examples set up an interesting dichotomy: that someone from the first group might find the safety measures of group two to be unsafe, and vice versa. Like art, our idea of safe is up to each of us and will change and morph over time. Safety can mean conventional medicine and doctors in white lab coats or safety can be Wrenwood and alternative medicine and yoga and discussion.

Safety is not necessarily about right and wrong, but about comfortability and stability. For those individuals living at Wrenwood, finding inner strength and a community of likeminded people may be the medicine they need to improve. For Carol, her safety may never be found and she may never find her path forward. Those whitecoat doctors cannot seem to find anything wrong in her tests, thus pushing her off into the desert. At Wrenwood, some discoveries and improvements may have been made, but how does the film end? With Carol staring at herself in the mirror, in total isolation, repeating the phrase “I love you” without any real conviction. This isolation she finds in the igloo is the same isolation she has when she is within her gorgeous house, which leads me to believe that solitude may be key for Carol. Her fascination with Lester is not rooted in pity or the oddity of his behavior – it is recognition. Lester is the end point of her trajectory – on the periphery, masked, silent. For Carol to survive in a world that will not accommodate her, she may have to disappear from it – a lonesome journey of self-discovery ahead of her. That is what makes Safe so haunting, and so timeless. It is not a story of triumph over illness. It is a story about what happens when no one believes you are sick—and you start to believe it yourself. In the end, the safest place for Carol may be the farthest from everyone else.