Humans generally think of time in a linear fashion. We move forward and we think back. Our existence on this plane is a slow crawl toward both our individual selves and our species’ oblivion. We can see clearly what has come before as if we walk backwards on this timeline. It’s as if our consciousness is strapped into a baby’s car seat and it can only perceive things after they happen. We’re children looking out the car window to see a tree or power pole as the car speeds past. While we mortals are content with continuing to exist this way, writer-director Christopher Nolan chooses to turn any which way he pleases and even leaps off the linear path to skate figure eights among the stars with other fourth dimensional beings.

There is a constant sense of being off balance when watching a Christopher Nolan film. It’s because he’s taking us along with him, through his thoughts and the vast universes they contain. His films based in the past look to the future and his films based in the future look to the past as they reach out in conversation with each other. Those conversations revolve around deeply human ideas and themes. He has his characters love, fight for survival, hope for the best, and be ambitious in going for something they want.

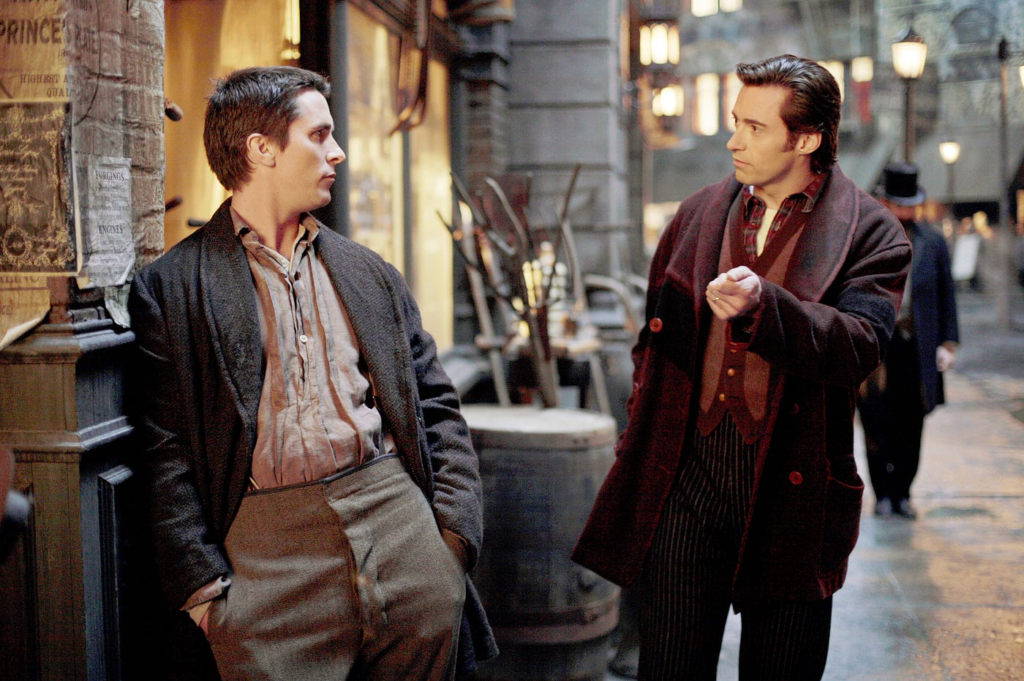

The Prestige is about corporate espionage. Though, its corporations, its brands, are the fame and fortunes of two Gilded Age magicians. Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) is driven by a need to be the smartest person in the room. Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) is driven by his need to be adored. Their rivalry is bitter and violent as they try to get inside the other’s head. They push the boundaries of their craft beyond the limits of their very humanity leaving friends, assistants, and family in their wake.

Inception is about corporate espionage. Its corporations are the traditional kinds with multinational holdings, diversified portfolios, stocks, and deep secrets. Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his crew are the best at extracting those secrets. They enter their mark’s unconscious mind through dreams, making the person feel safe, threatened, confused, or anything else in order to push them to reveal their secrets. The dream world provides a way to connect them to a deeper part of themselves, which could potentially change how they see the ones they love and bring a little humanity back to the corporate entity.

The Prestige and Inception are intertwined in this way, making a circle with two points. At one end is love and at the other is ambition. Borden and Angier start as men who love. They love the life of illusions and fantasy. They love people who are engaged by their passion and their drive, but it isn’t enough for the two of them to have one person, one family who see them as brilliant. There must be more people to impress, more adulation, more awestruck faces. Their curve bends toward ambition. Their talents demand more. They must be better. They need something more than who they are. The secrets they keep of the illusions they perform drive each man to his final fate, each alone in his own way, still hoping to have the final boast.

This is where Inception begins its journey in the arc. The characters of Robert (Cillian Murphy) and Saito (Ken Watanabe) are titans of industry. The two of them head rival companies that have reached a plateau in their growth. Cobb is the man in the middle. He isn’t vastly wealthy or an executive, but he is the best at what he does even if what he does won’t let him forget how he got his reputation. These men meet in a space devoid of their stations in life. It’s a playing field with only a small semblance of control, built to manipulate and implant an idea. They play with emotions, change relationships, and find a way to understand what is actually important in life. Regardless of the impetus for the catharsis Robert experiences, it’s still real as he put his real memories into it. Regardless of the malevolent creature Mal (Marion Cotillard) has morphed into in Cobb’s memories, his own catharsis and forgiveness is real even if she isn’t. Regardless of why he wanted to tag along on a trip of corporate espionage, Saito finds his lifetime trapped in a dream to be a chance at a do over, to maybe do things differently. Their ambitions curve, through their own volition or though a simple coercion, toward the love they’ve always needed in their lives.

Can ambition and love coexist? It’s a tough question, but it’s probable that if you only look toward the future, you will forget the past. It’s also probable that remembering the past can benefit the future. Yet the future, as much as we strive toward it, isn’t a fixed point. It isn’t certain, even with credible foresight. One little detail or idea will throw any trajectory off course.

Oppenheimer tells a story of a man who sees into the future. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) stands at the precipice of human discovery and he leaps off of it. He takes theoretical physics into the realm of the real and gives humanity the most grim and terrible possible fate of nuclear annihilation. Whatever his intentions in successfully building and testing an atomic bomb, his spark sets the world on edge with volatile fingers hovering on buttons. In his hour of realization, Oppenheimer strives to put the terror back in the box. He sees the devastation his invention will cause. He tries in vain to rally against its proliferation. He foresaw the cataclysm of a flawed humanity with the power to wipe itself from the universe. Oppenheimer sinks into the dire depths of a quote he often repeats from the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

Interstellar tells a story of a man who only sees the past. Coop (Matthew McConaughey) has never given up the stars he wanted to explore as a pilot for NASA. Even as Earth’s population dwindles and her resources dwindle even faster, Coop wants people to remember who they were. When he stumbles upon a reconstituted NASA he barely hesitates after hearing their pitch for a last ditch effort at saving humanity from extinction. Though, on the mission he can’t see the survival of the human race for the people he and his fellow astronauts Brand (Anne Hathaway), Romilly (David Gyasi), and Doyle (Wes Bentley) left behind. As the years slip by, Coop feels farther from his goal, farther from the spirit of the oft quoted poem “Do not go gentle into that good night,” by Dylan Thomas.

Both Oppenheimer and Interstellar offer visions on what it takes to survive. Oppenheimer attempts to delve into the psyche of a man who comes to regret his creation and sees the hubris of the leaders that will exploit it. Theory is one thing, but practicality is an entire beast on its own. They’re two sides of the survival coin. On the one hand, the Nazi war machine, fueled by hate and misguided belief, is a decimating force that must be stopped. On the other hand, this bomb, if proliferated and used, could destroy the entirety of the world for something so petty as lines on a map and a difference in ideology. Both coexist within Oppenheimer. He sees the need to end the suffering of millions with the deaths of thousands, but there will be a hunger for this weapon and for the destruction of enemies.

Interstellar has posited that man’s other hubris of exploiting our natural world will lead to devastation. Coop sees humanity’s future as one unbound by this world. He seeks survival in the ideas of generations of humans before him that to seek, explore, and journey is the only way to find something more palatable. He seeks, explores, and journeys with the purpose of the perpetuation of his own family, though. It’s what sets him apart from the scientists he travels with, this need not for humanity to continue, but for the people still on Earth to have a chance at the life taken from them by their forebears. A life without the need for scraping in the dirt for a hope of survival.

Is survival about knowing how to affect the future or caring about what we had in the past? If there was a way for humans to travel both forward and backward on our timeline, a new theory is broached because the past is knowable and the future is unknowable. It’s when we start to think of the repercussions of a simple change that theory splits itself. One theory dictates that if one with foreknowledge traveled to the past, their presence would then completely change the timeline. A branch would develop at that point and a new structure would form even as our person remembers their timeline. Events beyond that point would be different from where time branched. Another theory is that the timeline is fate, that whatever happened, happened. That person with foreknowledge was always meant to arrive and whatever they do cannot change what is meant to happen.

Dunkirk is a film about hope for the future. The film splits into three different timelines, which change our perception of the situation at hand as they progress. The men stuck on the beach waiting for rescue try every scheme and ploy they can think of to get off the beach and into a ship heading back to England. The small craft coming across the English Channel seek to help any and all they can find. The Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots hope they’re not too late and do all they can to make that true. The fate of one man affects another, affects another. Yet, even as the odds pile up, none of them gives up hope in the horizon in front of them.

Tenet is a film about hope lying somewhere in the past. The Protagonist (John David Washington) is kept on his toes by a shadowy organization. The organization’s aim is to stop a future power from sending an incredibly powerful weapon back in time. Sort of. In a macro way the temporal logistics of Tenet are confounding, but in the micro world of the characters it is about how changing fate for one’s self can have an impact on changing fate for the world as a whole. There is hope in the changing of one’s past circumstances. Or at least in the attempt to change it.

Dunkirk and Tenet offer different ways of time travel as a vehicle for hope. Dunkirk isn’t specifically about time travel, but obtusely it uses the ideas of a branching timeline. We see events from different angles. Their drama is heightened even if we know the outcome presented in one of the other timelines because something could change, or not change, but our fundamental knowledge of the outcome of events is skewed. When Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance) and crew encounter the shivering soldier (Cillian Murphy), he’s atop the nearly sunk hull of a warship hit by a torpedo from a U-boat. It’s not until Tommy (Fionn Whitehead), Gibson (Aneurin Barnard), and Alex (Harry Styles) are rescued from the second shipwreck they’re a part of that we see the shivering soldier in the past, commanding men in a row boat. Suddenly our perception of the timeline shifts with our hopes for these men. As they progress, they get farther from that fate, as if our seeing the future changed what happened to them in the past. The opposite is true when Farrier (Tom Hardy) takes the wave of his partner Collins (Jack Lowden) as a sign of safety, when in a different timeline, his wave is one of desperation as the water begins to fill his cockpit. The timelines shift our perspective and change the future as they eventually merge and then split again. They fill us with hope and dread simultaneously as they change our perception.

Tenet is the opposite in terms of its fatalism. Everything that happens within their timeline is because someone put the pieces into place and they will always be in those places no matter who inverts themselves or why. That’s where the hope of the film lies even if the audience and the characters don’t know it. It takes The Protagonist seeing the moves as they happen, and understanding that they are moves he can reverse engineer, which helps him grasp his place in the greater conflict. His analytical mind interprets and then weaves the narrative as he remembers it, which gives him hope in a favorable outcome even if his being two moves ahead means he has to take sixteen moves back to get back to his two moves ahead in the right way and at the right time. His knowledge of the past informs how he hopes to conquer the future.

Could it be possible for hope to exist if the future is known? There aren’t forgone conclusions within the branching of timelines and even a past and future bound by the shared fate of an omniscient being isn’t a completely solid foundation. Human interference will always put the future in doubt. People will always learn to love and even more unpredictably they will learn to want. The future is shaped by what has happened and what people want to happen. Force of will turns the wheels of our existence.

Christopher Nolan’s films exist outside of a linear scope. Even his films that are ostensibly set in the present exist like a fractured mirror of time. He uses the filmmaker’s art to restructure how we perceive stories. We’re shown exactly what we’re meant to be shown when we’re ready to see it. Nolan puts his characters’ lives into a blender and shows us their capacity for love and hope as well as their dark and light ambitions toward survival. He weaves these themes throughout his films to take us beyond our sense of acceptance about linear time. Nolan shows us how the past and the future are in conversation with one another. He shows us that the true power of cinema is in how the time is used and how a film we’ve seen takes on a new meaning the second time because we remember its future in order to interpret its past.