Director: Bi Gan

Writers: Bi Gan

Stars: Jackson Yee, Shu Qi, Mark Chao

Synopsis: A woman’s consciousness falls into an eternal time zone during a surgical procedure. Trapped in many dreams, she finds the corpse of an android and tries to wake him up by telling endless stories.

With only two feature-length projects to his name, Bi Gan has become one of the most followed and anticipated filmmakers among cinephiles working today. He has a distinctive approach to storytelling. Ambition is at the forefront of his work, with each narrative and stylistic choice diverging boldly from convention. Poetry and magical realism intertwine, as his focus on atmosphere and sensory details adds an unpredictable nature to his projects. You never know what you are going to get from Bi Gan, and his latest work, Resurrection (screened in competition at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Special Jury Prize), has him heading toward a completely different direction–one that is unexpected yet ultimately magical in every aspect of the film.

Both an ode to cinema and a plea to continue dreaming, Bi Gan presents his most audacious and crafty story to date, featuring sci-fi elements and fantasy quandaries set against five distinct canvases that evoke various styles and techniques from cinematic history. It is a thing of beauty, and also a confusing foray into the unknown. But through the bewilderment, there is a poignancy and wonder, something that few filmmakers can handle properly, which makes Bi Gan a special kind of director. The first fifteen to twenty minutes or so are dedicated to explaining the Blade Runner-like premise to the audience, set in a dystopian future. This is a time when people have found a way to live longer if they don’t dream.

It is illegal now to do so, but some still dream and venture into their imagination, called “fantasmers”–living shorter yet more vibrant, joyous lives by dreaming. They enter these dream states, each resembling an era of cinematic history. However, there are some repercussions to these entries into the plains. It alters reality, causing time jumps and changes, which is why the “big others”, having the ability to tell reality from dreams, are sent to hunt down the fantasmers. Hence, the Blade Runner similarities; instead of replicants and blade runners, you have fantasmers and the big others. One of these fantasmers is played by Jackson Yee, running amongst the supernatural, and he’s being chased by Miss Shu (Shu Qi), the chosen big other for his case.

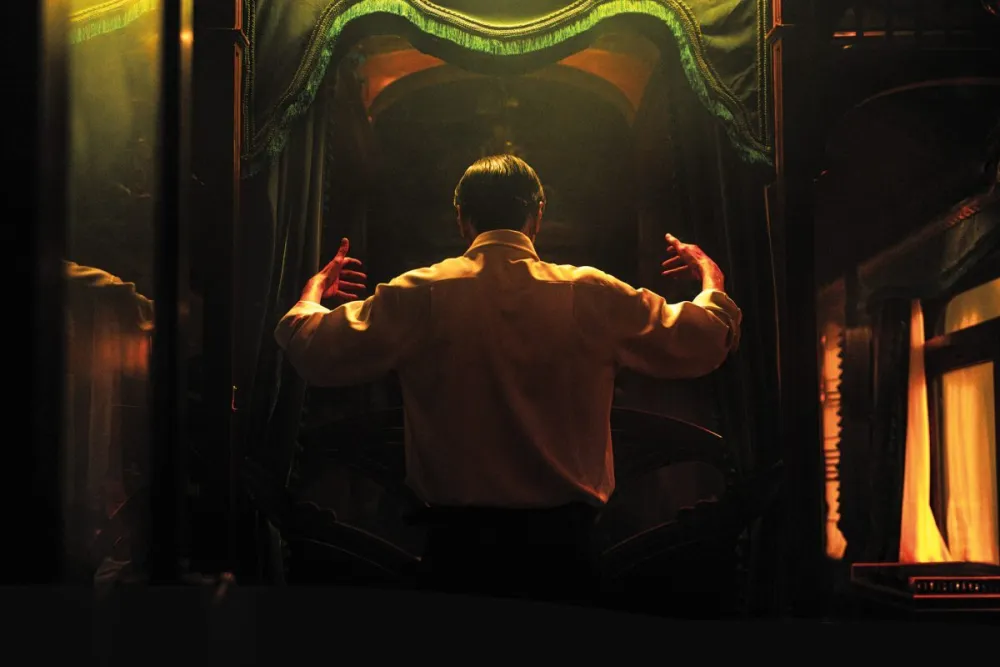

The sequence is shot, and references many classics from the silent era and its masters–F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu and Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari are amongst the few easily recognizable ones. You immediately sense the cinematic fervor and passion of Bi Gan, which he will throughout Resurrection provide a film class’ worth of nods and honors, ranging from the beginning of the medium with the Lumière brothers to the present day with Wong Kar-Wai and other acclaimed contemporary Asian filmmakers. After this segment, the fantasmer is caught by the significant other; he is bound to die because of his crimes. But before he dies, Miss Shu grants him one last journey through the dream states, where he has a chance to mend old wounds and undo some of his biggest regrets.

These last moments of mercy are presented in thirty-minute segments, almost like independent shorts, where he plays a different person in a period distant from his own. Vampires, knocked-out teeth, war interrogators, mirror shops, and street scammers drift across the screen. These surreal images fragment into memories and imagined realities—creations born from the mind of a dreamer, much like Bi Gan himself. That’s the film’s crux overall: the existentialism and philosophical elements contained in dreams and during our respective creative processes. Dreams tantalize us; nightmares invoke dread. Both conjure something difficult to explain, or even recall in its entirety. They live on the edge of perception, fleeting and fragile, yet capable of altering our emotions and thoughts in ways that linger before vanishing.

A study demonstrated that the isolation and loneliness caused by the pandemic led to people having more bizarre and vivid dreams. Since the original film that Bi Gan was going to write was completely different, this phenomenon inspired the Chinese filmmaker to craft his latest, which feels like lucid, vivid retellings from REM-sleep hallucinations, in the best way possible. Bi Gan traverses this liminal terrain, where memory, dreams, nightmares, and existence dissolve into one another, causing Resurrection to feel like a man trying to recount his own life through cinema — the medium’s history seen through the eyes of a slowly fading vision. And every single move, whether coherent or disorganized, is done with that in mind, departing from his past forms and structures to paint an ambitious canvas where, in each chapter, there is a new technique applied.

In an era when a great majority of directors with the gift of making films lack originality, Bi Gan inspires us to venture into the unknown. He wants us to be creative and distinct, contemplative and artistic, in everything we do. There are more philosophical elements in Resurrection that I might explore in more detail with further viewings. But what Bi Gan provides is what contemporary cinema lacks: originality, boldness, and the panache to be equally audacious and awe-inspiring. And it is not just him, but a great majority of the films playing at this year’s Cannes Film Festival also invoked that for me–Masha Schilinski’s Sound of Falling, Oliver Laxe’s Sirat, Julia Ducournau’s Alpha, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s The Secret Agent, amongst others. This is a plunge into memory and myth, where we are invited to surrender to the dream logic and venture into imaginative worlds crafted with admiration for the seventh art.