“MY NAME IS JOHN FORD, I MAKE WESTERNS”

I, until a few years ago, did not really like Westerns. I rejected them, refusing to give them the time of day as I boxed them in as “movies for boys” that catered to the male sensibility, much like how The Woman’s Picture (aka female-led melodramas) cater to a certain feminine taste. Thankfully, I let go of this preconceived notion to open myself up to one of the most fascinating, reflective genres of cinema. With the impending release of Kevin Costner’s Horizon, now seems like the perfect time to gaze at the genre with a little bit of freedom.

The Western is just about the oldest movie genre we have, taking advantage of the “Wild West Shows” so popular at the turn of the century to entertain audiences with simple stories of action and adventure. Of course, like any genre, it evolved over time to the era’s tastes and sensibilities. While dipping in the 1930s, the genre had a resurgence in the following decades, surely as a result of newfound American patriotism inspired by the Second World War, and later technological innovations, such as widescreen and technicolor. In the 21st century, Westerns are often highly self-reflective, putting a critical lens on how we build our mythologies of greatness and heroism. Within the fables of cowboys and gunmen (which have their own merits) lie a plethora of tales of morality, justice, and humanity. If you’re hesitant about the genre, I have a handful of titles to recommend that might change your mind. No longer is the genre a boys’ club, it now serves as a playground of possibility for filmmakers and storytellers of all backgrounds and sensibilities.

After the cultural juggernaut of Yellowstone, and Kevin Costner’s Horizon set to premiere at Cannes, now seems like the perfect time to gaze at the genre with a little bit of freedom, and the benefit of learned hindsight.

Red River

This essential Howard Hawks film is a classic, no doubt. Personally, Red River is the Western that made me like Westerns. It’s a knockout of a film, essentially Mutiny on the Bounty with cattle instead of a boat. John Wayne, the Big Kahuna of the genre, teams up with newcomer pretty boy Montgomery Clift to offer a considerate account of post-war masculinity. A playground of large scale scenery and intimate moments, Red River is the ideal place for anyone looking to dip their toe into the wonderful world of Westerns.

Yojimbo

Akira Kurosawa, through his tales of samurai and ronin, perhaps had a greater impact on the American Western than any other filmmaker. Yojimbo follows Kurosawa’s frequent collaborator (and regulation hottie) Toshiro Mifune as a bodyguard for hire, who uses his unmatched skills to liberate a small defenseless Japanese village from gangster warfare. The film would eventually be remade by Sergio Leone as A Fistful of Dollars, establishing Clint Eastwood as a leading man of the genre. In Yojimbo, Kurosawa and Mifune masterfully balance action, drama, and comedy to create a film that transcends era, country, and genre.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Admittedly, a good amount of Westerns, especially those of the earliest years of Hollywood, hold a particularly nostalgic, proud view of the old west, wrapped up in injustice and a romanticized view of Manifest Destiny. That is to say, not many Western films concern themselves with stories of the marginalized. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford, is an exception to that rule. Starring Jimmy Stewart in one of his most Jimmy Stewart-iest roles, the film concerns a lawyer who attempts to better a community through education in law and justice, all the while protecting it from a feared gunman named Liberty Valance. In one notable scene, while teaching school children and adults alike about the laws of the land, a local farmhand named Pompey, played by African-American actor Woody Strode, can’t quite remember the words to the Declaration of Independence, stumbling over: “all men are created equal. “That’s alright Pompey” says Stewart, “a lot of people forget that part”. In this film, the gunfights take a backseat to the struggle of building a community based on humanity and justice, resulting in a remarkably modern, rewatchable piece of cinema.

First Cow

Kelly Reichardt approaches the western through a lens of tenderness and empathy, illustrating a tale of two men who find solace in one another’s company in the Pacific northwest. Reichardt offers a new perspective on the west, leaving behind vast barren landscapes in favor of towering trees and vibrant greenery through a decidedly optimistic, uncynical framework. By doing so, Reichardt, who is no stranger to the genre, recontextualizes the western away from the confines of male toxicity and isolation to one of kindness and community.

The Ox-Bow Incident

William A. Wellman, arguably one of the most underrated directors of the early studio system, masterfully directs this haunting and devastating tale of injustice and loss of innocence. The Ox-Bow Incident is the ultimate “anti-Western”, throwing everything the genre had previously taught audiences about frontier justice and unchecked masculinity into question. This world is lawless, subject to mob-mentality with little thought or consideration. The film is a key predecessor to the 1957 Kubrick masterpiece Paths of Glory, and foreshadows the devastation caused by McCarthyism and Cold War paranoia in the following years.

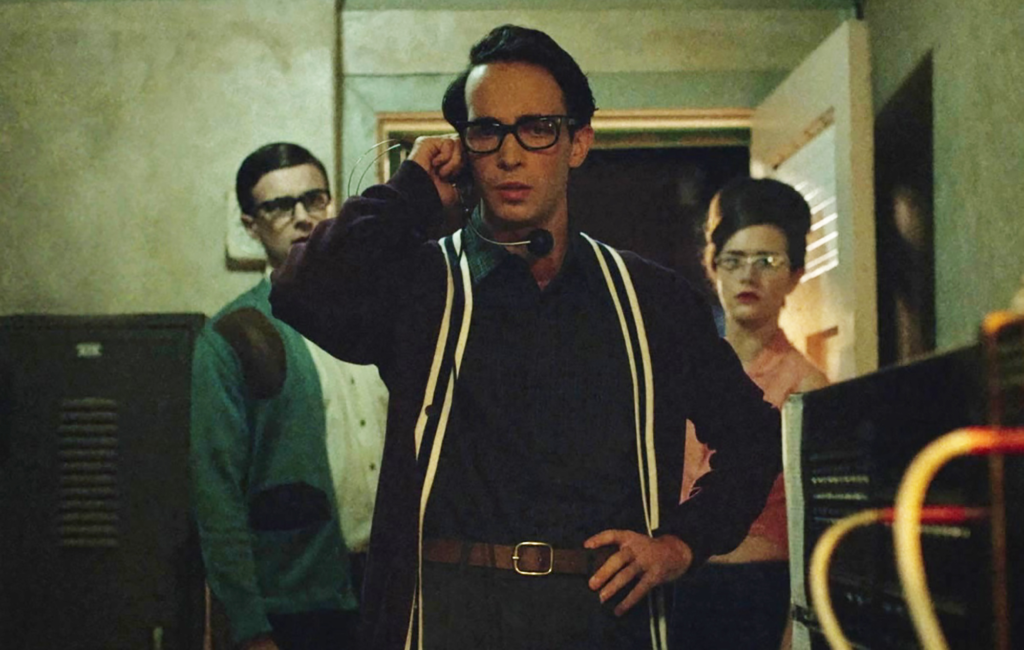

The Vast of Night

Who knows why cowboys and aliens look so good together? Perhaps it’s the vastness of the western landscape that resembles the surface of a faraway planet, or that so many UFO sightings happen to occur in the skies of the American southwest (thanks Area 51). That marriage comes together perfectly in Andrew Patterson’s The Vast of Night, an underseen Twilight Zone-esque thriller that came out during the liminal period of 2020. In this 1950’s-set film, a young disc jockey and teenage switchboard operator in rural New Mexico are brought together by mysterious sightings in the sky and unexplained radio interference. The film moves with great patience, relishing in long takes and impossible camera tricks to create something both eerie and magical.

City Girl

City Girl perhaps doesn’t go “west” enough to be considered a true-blue “Western”, but embodies many of the themes so frequently represented in the genre, illustrating a divide between city and countryside, the metropolitan and the pastoral during a period of immense economic hardship and uncertainty. While the film is fairly light in its story, its true star is its stunning cinematography and editing that takes cues from the Soviet Montage and German Expressionism, and would go on to inspire the likes of Terrence Malick, whose depictions of American landscapes are some of the most beautiful ever captured on film.

Badlands

Perhaps the ultimate portrayal of the hopelessness of the American Dream, Terrence Malick depicts a story of violence and destruction through beauty and patience. Badlands is based on the true story of a spree killer and his underage “girlfriend”, told through the eyes of the young girl who looks at her ex-con, junkman of a boyfriend as her ultimate escape and chance at freedom. Through the chillingly naive narration by the genius Sissy Spacek and an all-time performance by Martin Sheen, Malick uses the beautiful landscapes of middle America to illustrate this tale of youthful ennui and deadly romance on the run.

Hud

Paul Newman. Patricia Neal. Need I say more? Hud is a prodigal-son story about a rancher trying to wrangle his alcoholic, womanizing son from further corruption and destruction. The film is a masterclass of drama and acting, blending the old school style of Melvyn Douglas with the hip, new wave style of Neal and Newman. It’s hard to imagine Newman in such a selfish, despicable role, yet he pulls off the role with perfect precision alongside his stellar supporting cast. Another star of the film is legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe in one of his greatest feats of black and white filmmaking, creating intimacy and unexpected beauty within scenes of conflict and heartbreak.

Whether it’s man vs. environment, man vs. society, or man vs. self, the Western film offers the perfect setting for both introspection and adventure, and further consideration of the myths we tell about America and ourselves. Of course, not every western film bothers with matters of empathy, but no genre is perfect. It is my hope that by watching one of these films, you will be able to find a complicated, at times beautiful, story hidden underneath a rough exterior.