The 2024 cinematic year was filled with contradictions, disappointments, mediocrity, and lackluster pictures. But, many visionary projects broke the medium’s conventions in fascinating ways. These contain a potent, sensory visual language curated by some of the most brilliant minds in the medium, as well as new ones that have emerged–both veterans and newcomers from different places around the world who want to provide their perspectives on the world, our past, present, and potential futures, using their respective canvas as a way to pour their worries, joys, and melancholy for us to digest, reflect, and ponder. As always, many will argue that this year was weak. But if you know where to look, you will find beautiful gems waiting for you to bask in their greatness and stature. The films compiled in this Top 10 list were some of the ones that spoke to me and my cinematic sensibilities the most. So, here are some words on my favorite films of 2024, from Luca Guadagnino’s delicate and melancholic adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ ‘Queer’ to a brilliant debut by Lucy Kerr that has remained in my mind since I saw it last year at the Locarno Film Festival, and coincidentally has motivated me to pick up photography. The following are arranged in alphabetical order because I don’t like ranking films or putting one on top of the other, especially when I care and cherish all of the movies mentioned below.

First, some honorable mentions: All We Imagine as Light, Babygirl, The Brutalist, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, Good One, I’m Still Here, The Settlers, The Substance

The Beast (La Bête) (Directed by Bertrand Bonello)

Bertrand Bonello is one of those directors whose early work, The Pornographer and Tiresia, I disliked heavily due to his pretentious and self-indulgent footing. However, in the last couple of years, he has taken a different route–tonally, stylistically, and narrative-wise more ambitious–with more panache to his visual language, becoming one of the most creative and fascinating voices to follow in French Cinema. He shifted his focus from indulgence to reinvention with pieces like Zombie Child and Coma, both criminally underseen and underrated. But now, with The Beast, his loose adaptation of Henry James’ short yet multilayered book ‘The Beast of the Jungle’, he creates something way different than before: a Matryoshka doll-like exploration of the erasure of emotions, doomed lovers, and artificial intelligence, similar to when the Wachowskis made Cloud Atlas, yet with a more idiosyncratic and unconventional note which’s big swings land heavily and emotionally. Through fractured timelines and broken hearts, Bonello navigates this tricky story into weird territories that made me think about everything and anything, from the loss of tradition to the worries about a technology-focused future where love is at the screen’s glance and not met by the physical and psychological. A year after I saw the film, I am still baffled by how this worked out.

Caligula: The Ultimate Cut (Directed by Tinto Brass)

In one of the most impressive acts of saving a film from the hell that it was in, Caligula: The Ultimate Cut is the new definitive version of the ‘70s film with the most backlash that gives way to Tinto Brass’s original vision. Technically, this is not a 2024 film, as it is a restoration and re-edit of the 1979 film Caligula. (This is not the only time I will try to cheat on this list.) But, due to it having nearly ninety percent of new material placed onto the film–removing the excess sex and violence that financier Bob Guccione shot and pasted on the film, basically flipping it from a porno picture to a study of excess and power in Ancient Rome–I decided that, for me, it does count. To see how the botched theatrical cut was met with backlash and hate from the cast and crew to the audience and now seeing this near masterwork is nothing but impressive, showing how restorations do serve an excellent service in reviving lost cinema–fractured pieces of art that one thought could not be saved, yet they are rescued by technicians and cinematic architects that want to preserve this medium. Caligula is now a staggering piece that works on many levels and is not just another project cursed by terrible financiers.

Close Your Eyes (Cerrar Los Ojos) (Directed by Víctor Erice)

Victor Erice is one of the best Spanish filmmakers ever to grace the world. He does not make films consistently, always with plenty of time between each feature. So, when one arrives, it is a special occasion for celebration. At 83 years old, Erice has been long-absent for several decades, doing occasional collaborative projects with Pedro Costa and Manoel de Oliveira. But the time has come; he has brought us his first feature film since 1992, Close Your Eyes (Cerrar Los Ojos). This film continues the strand of veteran filmmakers looking back at their legacies, careers, and fear of death alongside David Cronenberg, Francis Ford Coppola, Leos Carax, and Paul Schrader, to name a few. But these works all have their distinctive touch, the worries of the filmmakers attached and the reflection of their journeys from childhood to now, where a lot has changed both in and out of the art world. In Close Your Eyes, Erice reflects on his departures, the essence of memory, and the beauty of life’s passage through a self-reevaluation and a film-within-a-film format that provides optimism with the foreboding of the future’s uncertainty. A touching scene from Damian Chazelle’s Babylon (a film I loathe) reminded me of this film and its crux. Jean Smart and Brad Pitt’s respective characters discuss life and death and how cinema fits in between. The former says that each time a person sees a film, the people in them come alive for the duration of the movie–as she quotes: “And one day, all those films will be pulled from the vaults, and all their ghosts will dine together, and adventure together, go to the jungle, to war together.” Similarly, Erice is now reflecting on his work, its impact, and the long-lasting legacy of cinema as a whole, not only his contribution. He expands on this fracture that time has and invites the viewer to question their relationship with cinema–modern audiences to try and look at this powerful medium in ways that they haven’t before, not only see the surface but go further and see how these are memories that once were stuck inside the head of a creative being and is now shared to the world.

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Nu Aștepta Prea Mult de la Sfârșitul Lumii) (Directed by Radu Jude)

After delivering one of his least inspiring, yet still provocative, affairs with Bad Luck Banging or Looney Porn a few years back, Radu Jude delivers his most ambitious, complex, and experimental picture in Do Not Expect Too Much of the End of the World (Nu Aștepta Prea Mult de la Sfârșitul Lumii). It is a playful and testing metatextual exploration of capitalism, the 2020s influencer screen-infected era, and Romania’s political and societal history. The Romanian filmmaker interlaces his picture with Lucian Bratu’s 1980s work, Angela Moves On, to create a parallel portrait of how the world has changed and remained the same in many different aspects. As technology advances, the same exploits from the government are still predominant. Jude doesn’t shy away from pinpointing these injustices. Brave as always, he lets his thoughts about everything roam around this betwixt canvas. He uses real-life despair and cinematic absurdism to create a thought-provoking picture that remains poignant even in its most farcical sections riddled with mockery and questioning.

Family Portrait (Directed by Lucy Kerr) & Nickel Boys (Directed by RaMell Ross)

Yes, I know I am cheating by including two films into one spot, and now it is not “technically” a Top 10 List on my part. But there’s a reason I did so (apart from being unable to pick one or the other–note, I almost added a third one, but I know that is stretching this “cheating” too far). I paired these two films because of their singular, striking visual imagery, which has affected me since I saw each in their festival premieres. I just can’t take these images out of my head. In Family Portrait, Lucy Kerr creates some grounded, limited, haunting images that speak louder than monologues about the death of communication and our different versions of melancholy. Through the narrative of a woman wanting to reunite her family for a Christmas picture, she reflects on how we reflect those moments when we want to rapidly capture a moment passing us by and preserve it through photographs, videos, and other methods. We blink, and a month has passed. We blink again, and then a year goes by. Then that solemnity hits you… the longing of not being able to freeze time and memories becoming blurred. And all of that is done through simply constructed images: time through simple portraits. Then there’s RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys, which has some of these same elements through the cinematography by Jomo Fray–a unique and intriguing voice in the medium that curates striking images so effortlessly–and a POV lens. But, it is less dark and brooding and more poetic and embalmed in tragedy. The characters in the film travel down distanced yet collective paths where they believe that escaping physical trauma will cause their suffering to end. The playfulness in Nickel Boys comes from this intertwining between showing glimpses of hope and letting the characters and viewers know that this “escape” will not save you entirely and that there is still pain deep in your soul that will not be easy to cure. This touched me. This made me anxious and worried in the theater. However, since that element of hope is still punctured in the film, those worries become reflections, and that reflection ensures the viewer that everything will pass and healing will come.

It’s Not Me (C’est pas moi) (Directed by Leos Carax)

Leos Carax spills his mind, body, and soul in his cine-essay It’s Not Me (C’est pas moi), where he takes inspiration from his dear friend and French New Wave co-creator Jean-Luc Godard–saying goodbye to him in a cinematic form–to offer a “self-portrait” of his essence both on and off the art world. The French-Swiss director’s spirit is felt throughout the film, like a ghost who wanders through the world watching those it once cared for, Carax being one of them. From the collage feel of the project to the interlacing between social commentary and self-flection, the two filmmakers intertwine, hence why it is nearly impossible to separate It’s Not Me from Scénarios, Godard’s last short, two shorts that complement each creative mind and worries in the format they helped grow into a beautiful potent, and expressive medium. Carax, now sixty-three years old and one of the most fascinating cinematic voices working today, looks back at the past in all of its nostalgic and haunting glory and the troubled now–leaving you wondering, “Who is Leos Carax?”, which he answers in a poignant, dreamy manner, and “Who am I?”, you asking your inner self these same questions that Carax ponders in these 50 minutes.

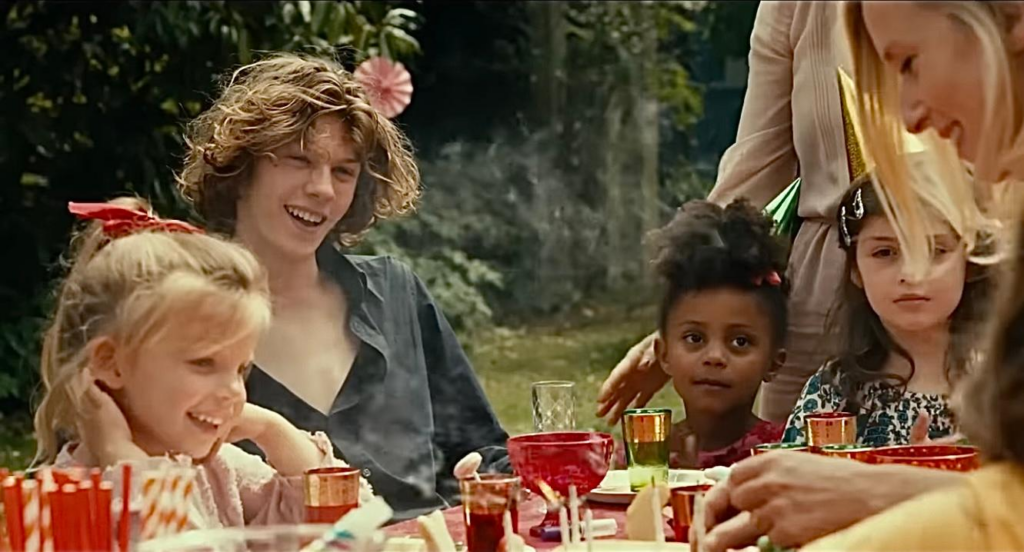

Last Summer (L’été dernier) (Directed by Catherine Breillat)

Catherine Breillat has been provoking audiences and thought since her directorial debut. Her latest film, Last Summer (L’été dernier), is yet another one of her pictures that does such a thing, but with a different tone. It is a remake of the Danish erotic-thriller by May el Toukhy, Queen of Hearts, where one of the few narrative changes made was switching Denmark’s icy setting to France’s sun-kissed streets. However, there is still a coldness to it. This feeling that emerges from the story comes via the reality of Breillat’s thematic exploration. Instead of being a one-sided shock factor that many American productions explore this type of narrative about an older woman grooming an innocent boy, Breillat is more interested in exploring what drove one to do such things–without leaving them as innocent–through a subtle, grounded manner that showers the film with brevity. It is an exercise in the likes of Gaspar Noe transitioning from Love to Vortex, with the dramatic sensibilities of Last Summer being long-term wound-inducing rather than cutthroat. And that is why the film becomes more piercing than some of her work.

Queer (Directed by Luca Guadagnino)

It is hard for me to talk about Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, which I believe is one of his best works to date, because of how invested I was in it–reading William S. Burrough’s book, researching Edward Hopper and Ego Schiele, whom I saw resemblances of in the postures of the bodies and the production design, as well as its the connection with Malcolm Lowry’s ‘Under the Volcano’. But I will try here to write a paragraph about why I love it so much. This intoxicating and melancholic story about a man so desperate for love and connection that he subjects himself to several forms of addiction, both literally and metaphorically, is so heart-rending and spiritual that it becomes a tragically euphoric experience, even in the few moments of happiness that are scattered throughout the runtime. Guadagnino is making a project that is dear to his heart. Burrough’s novel is an influential piece of literature that shaped his youth and artistic mind. However, he also makes a portrait of the influential Beat Generation writer in all of his desperateness and melancholy to connect the solemnity that Burroughs felt with the current generation’s despondency and isolation. I was transported to these locations through beautiful, delicate cinematic brush strokes that made me feel everything from a closer view. Each emotional pandering and heartache was felt because of the Italian filmmaker’s tactile touch.

Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus (Directed by Neo Sora)

In March of last year, Ryuichi Sakamoto, the legendary Japanese composer behind Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and The Last Emperor, passed away, leaving many film lovers and classical musical enjoyers heartbroken. His son, director and artist Neo Sora, has constructed a parting gift from him to all of us who have been pierced by one of his pieces–something special after his unfortunate departure. Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus is more than a concert documentary where Sakamoto plays some of his most significant pieces; it is a tribute and a goodbye. It has the feel of David Bowie’s ‘Blackstar’ and Leonard Cohen’s ‘You Want It Darker’, in the way that you sense that Sakamoto knew that time was simply running out. So he thought about his coda, one final piece of work to share with the world–playing for their funeral, a reflection method to face the next stage. And it is as emotionally staggering and heartbreaking as any other dramatic piece to release this year. As one piece ends and another begins, a massive wallop of sadness hits you like a sledgehammer as Sakamoto, weakened by his illness, continues to play these classic instrumental tracks with his head high, knowing he will soon head to the heavens.

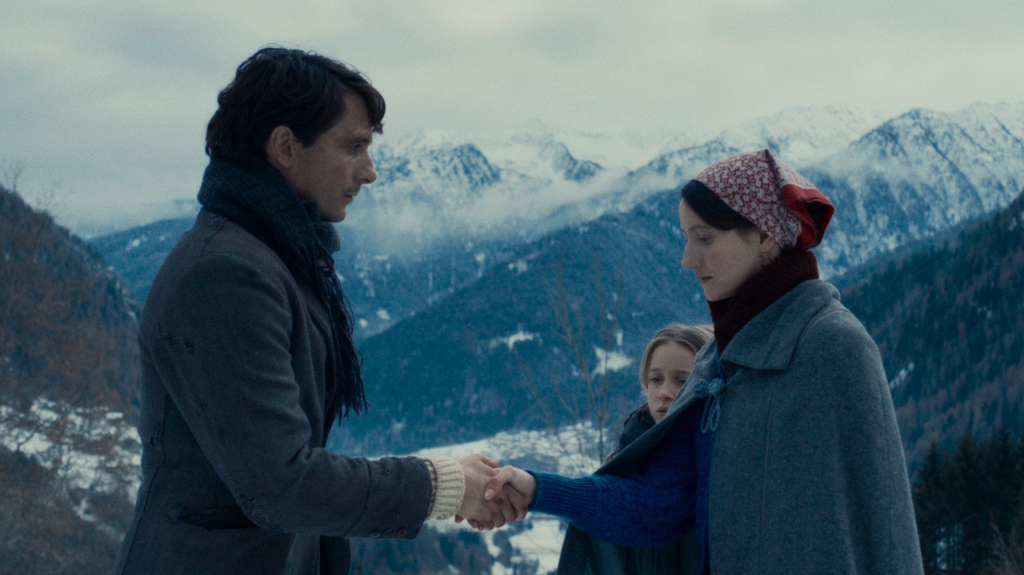

Vermiglio (Directed by Maura Delpero)

I may sound like a scratched record in this piece, but the visual language in Maura Delpero’s Vermiglio is mesmerizing. Something I look for in cinema is how these images on screen speak to me and make me think and reflect on the themes the director is planting and the worldview of today, tomorrow, and the past. Vermiglio has beauty and tragedy in each frame, shot by cinematographer Mikhail Krichman (Leviathan, Loveless), that talks about faith, femininity, and family through a snowy existentialist canvas that has some similarities with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s masterpiece Theorem in its backbone, yet without the elements of provocation and mystical eroticism. Delpero is a voice I have learned about for the first time this year. However, I hope to see more from her in the same vein as this: poetic instead of lyrical, subtle instead of overly emotional, and feeling like a photographic journey to the past instead of excessively expository.