She emerges from a coma with a single, burning purpose etched onto her soul: revenge, or as she says, “Kill Bill.”. Beatrix Kiddo, “The Bride,” codename Black Mamba (Uma Thurman), cuts a swathe through Kill Bill: Vol. 1, armed with righteous fury and a Hattori Hanzo sword. Quentin Tarantino’s 2003 masterpiece is a dazzling, blood-soaked homage to martial arts, spaghetti westerns, and exploitation cinema, driven by one of the most visceral quests for vengeance in film history. The structure, although not chronological, has a clear set of milestones to be met, the targets numbered on her “Death List Five,” the violence is balletic and brutal. Vol. 1 is a pure, uncut shot of adrenaline, a roaring rampage executed with stylistic flair.

Yet, Kill Bill: Vol. 2, released just six months later, represents far more than a mere continuation; it’s a fundamental reframing of the narrative. Crucially, the division results not merely in a split narrative, but in two films possessing strikingly distinct identities and rhythms. While viewed by some as two halves of a whole, this essay argues that they function most powerfully as standalone experiences.

Vol. 1 delivers the undiluted thrill and stylistic bravado of the revenge quest in its purest form. Vol. 2, on the other hand, decelerates, embracing a different aesthetic and tone, making space for reflection, consequence, and the pervasive counter-theme that defines it: regret. Appreciating each film’s unique atmosphere and tempo allows the profound shift between the adrenaline-fueled rampage and the melancholic reckoning to fully register.

It’s within this second, distinct film that the layers of stylized violence are peeled back to explore the squandered potential and the inescapable weight of the past haunting nearly every major character. By delving into the sorrow beneath the swordsmanship, Vol. 2 transforms the Kill Bill saga, particularly when considered as complementary, yet separate, works, from a superlative revenge fantasy into a richer, more complex, and ultimately tragic meditation on violence, identity, and the devastating cost of choices made.

Vol. 1: The Roaring Rampage (Standalone Thrill)

To appreciate the depth of the second film’s shift, one must first acknowledge the laser focus and self-contained power of Vol. 1 as a cinematic entity. Its brilliance lies in its commitment to the revenge narrative as the primary driving force. Beatrix’s mission is presented with absolute clarity. The list – O-Ren Ishii, Vernita Green, Budd, Elle Driver, Bill – lays out a tangible roadmap. The film employs stark black and white sequences in which Beatrix directly addresses the audience, leaving no ambiguity about her motivations. The hyper-stylized action, culminating in the breathtaking carnage at the House of Blue Leaves, creates a visceral, almost cathartic release for the audience, aligned perfectly with Beatrix’s drive. The visual language is sharp, often saturated; emphasizing impact and objective. It’s a film designed to make you root for the rampage, to feel the righteousness of the cause, even amidst the stylized gore. Vol. 1 is the finely honed edge of the blade, a complete and exhilarating experience in its own right, perfectly distilled action cinema.

Vol. 2: The Shadow of Regret Falls (A Separate Reckoning)

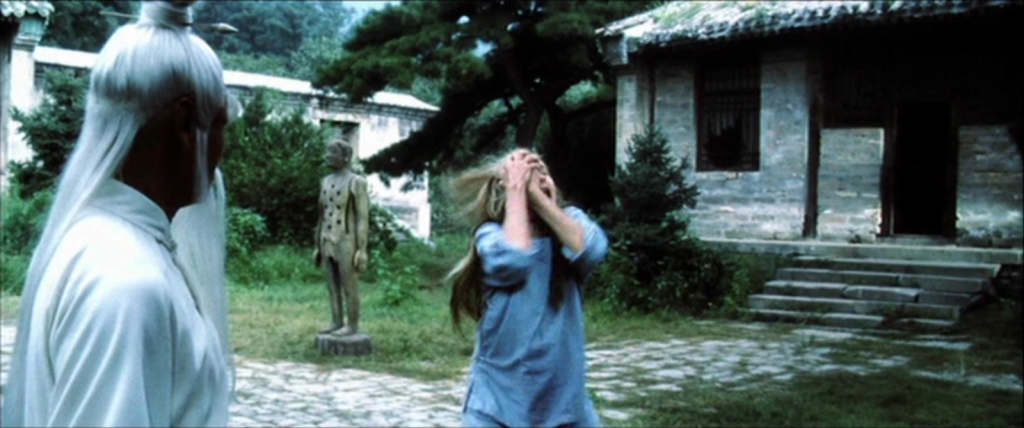

Vol. 2 functions as its own distinct piece, announcing its different intentions almost immediately. After the cliffhanger ending of the first film, the second installment opens not with immediate action, but with a crucial flashback: the wedding rehearsal massacre at Two Pines Chapel, El Paso. Here, placed strategically early, we witness the event that ignited Beatrix’s fury, but crucially, we see it through a different lens. We see Bill (David Carradine), not just as the monstrous mastermind, but as a man wrestling with complex emotions. His interaction with Beatrix) reveals layers of shared history, affection, and pain. Carradine’s portrayal imbues Bill with a palpable melancholy; his line, “I’m trying my best to be sweet,” delivered with a world-weary sigh, hints at the tragedy already unfolding. This scene immediately complicates the narrative. Bill isn’t just Target #1; he’s the man Beatrix loved, the father of her child, and his actions, while unforgivable, are colored by a sense of loss that permeates the rest of this distinct film.

This undercurrent of sorrow soon finds an explicit voice. In the desolate Texas landscape, Bill’s brother Budd (Michael Madsen) asks Elle Driver (Daryl Hannah), “Which ‘R’ are you filled with? Relief or regret?” While directed at Elle concerning Beatrix’s supposed demise, the question hangs heavy in the air, introducing regret as a conscious theme for this volume. From this point on, Vol. 2 deliberately explores the internal landscapes of its characters, revealing the rot beneath the surface caused by their past actions and lost possibilities, embracing a slower, more contemplative rhythm than its predecessor.

Budd: Squandered Potential and Symbolic Demise

If any character embodies the corrosive nature of regret in Vol. 2, it’s Budd. Once a member of the elite Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, codenamed Sidewinder, we find him working as a disgruntled bouncer at a grimy strip club (“I gotta clean the toilets after you?”), living in a dilapidated trailer choked by dust and decay. Madsen plays him with a slumped, weary physicality that speaks volumes of defeat. His clothes are stained, his mannerisms careless, even the way he makes a margarita screams apathy. This isn’t just a fall from grace; it is a self-imposed exile, a deliberate wallowing in squalor.

His dialogue drips with resignation and bitterness, most tellingly when Bill visits to warn him about Beatrix’s approach. “That woman deserves her revenge,” Budd states flatly. “And we deserve to die.” It’s a stark admission of guilt, an acceptance of consequence from the chapel massacre, or perhaps other unnamed sins. Budd is notably the only character that appears to openly express any remorse about the life he has lived. He seems to have chosen this life as a form of penance, a purgatory while awaiting damnation, convinced of his own lack of worth.

The handling of his Hattori Hanzo sword, a gift from Bill, symbolizing his past prowess and their fraternal bond is deeply revealing. He lies to Bill, claiming he pawned it for a pittance, partly to hurt his brother by feigning disrespect for the gift, partly to project indifference to the life and skills he left behind. But he kept it hidden away. This retention hints at a connection to his former self, his skills, and his brother that isn’t entirely severed. It’s a relic of squandered potential, a tangible link to a past he simultaneously regrets and perhaps misses, a symbol of the warrior identity he couldn’t fully discard even in his deliberate seclusion from civilization.

Budd’s brief, brutal victory over Beatrix, achieved not with finesse but with a pragmatic shotgun blast (“Bang bang!”) to the chest filled with rock salt and a subsequent live burial is a final flicker of his old competence. It demonstrates a grounded, if crude, effectiveness, anticipating her rather than meeting her head-on like O-Ren. His approach reflects a man stripped of pretense; unlike O-Ren seeking honor in combat, Budd simply seeks an end, mirroring his own resignation. His choice to bury her alive, while seemingly ensuring her death, leaves a sliver of chance, perhaps hinting at a subconscious reluctance to do the deed.

However, his death soon after is steeped in pathetic irony and potent symbolism. Having bested the legendary Black Mamba, Budd grows complacent, blinded by greed as Elle arrives with a suitcase supposedly full of cash for the Hanzo sword. He fails to see the betrayal coming. Elle, ever the opportunist, has hidden a deadly black mamba snake inside the suitcase. As Budd reaches for the money, the snake strikes, killing him swiftly. The symbolism is crushing: Budd, the Sidewinder, is killed by a Black Mamba, the namesake of the woman he thought he’d conquered. He’s undone not directly by Beatrix, but by the greed and treachery of another Viper, using Beatrix’s symbol. It underscores the nature of the violent world he inhabited and serves as a grim commentary on his ultimate defeat – defeated by arrogance, greed, and by the force he underestimated. He is a truly tragic figure, crushed by his past choices and dispatched by an emblem of his failure.

Elle Driver: Ambition Untouched by Remorse, Tormented by Symbol

Where Budd drowns in regret, Elle Driver, Codename: California Mountain Snake, actively rejects it, embodying ambition curdled into pure, venomous bitterness. Her defining characteristics aren’t regret, but ambition and contempt. Her rivalry with Beatrix is palpable, fueled by deep-seated professional jealousy and personal insecurity. She hates Beatrix but respects her skill and sets out to prove herself superior, especially in Bill’s eyes. Her relationship with Bill is forever shadowed by Beatrix’s ghost.

Elle’s cruelty is most evident in her treatment of Pai Mei (Gordon Liu), the legendary martial arts master who trained both her and Beatrix. She boasts of poisoning him as revenge for plucking out her eye, calling him a “miserable old fool.” This isn’t an act born of regret or complex motivation; it’s pure spite, likely stemming from her inability to meet Pai Mei’s exacting standards, unlike Beatrix. Killing him was an act of pathetic rebellion against a master she couldn’t conquer, and gloating about it to Beatrix is designed purely to inflict pain. Her actions suggest a festering resentment, perceiving Pai Mei’s harshness towards her contrasted with his respect for Beatrix as a personal slight worthy of lethal punishment.

Elle represents the path of violence without introspection or remorse, let alone regret. Consequently, her fate feels less like tragedy and more like chillingly direct karmic justice, again laced with potent symbolism. After a vicious fight in Budd’s trailer, Beatrix plucks out Elle’s remaining eye, mirroring Pai Mei’s fate at Elle’s hands. But Beatrix doesn’t kill her. Instead, she leaves the now blind Elle thrashing and screaming inside the trailer with the black mamba still loose, the very snake Elle had brought to kill Budd. Like Budd, Elle is undone by the Black Mamba, Beatrix’s symbol. While Budd’s death felt like consequence meeting greed, Elle’s fate is arguably crueler: left alive, blind, and tormented by the physical embodiment of her rival and her own treachery. It’s a grimly satisfying, symbolically resonant end for the viper consumed by her own venom.

Bill: The Melancholy Monarch

At the heart of the saga’s turn towards regret stands Bill himself. David Carradine’s performance is a masterclass in understated complexity. Beneath the suave exterior, the philosophical musings, and the moments of genuine paternal warmth towards B.B. (their Daughter), lies a profound melancholy. It’s visible in the weariness in his eyes during the wedding rehearsal flashback, the slight hesitation before critical lines, the calm yet heavy tone of his voice.

His use of truth serum on Beatrix in their final confrontation speaks volumes, not just of his mistrust born from hurt, but of a desperate need to understand the woman he loved and tried to kill. His famous “Superman” monologue, ostensibly about Beatrix’s killer nature, can also be read as Bill rationalizing his own inability to live a “normal” life, perhaps regretting that his inherent nature, his “Superman” identity, prevents him from ever truly being “Clark Kent” and finding simple peace.

Beatrix’s understanding that Bill was capable of extreme violence and revenge, but her almost naive belief that he could not, would not do that to her is an important statement about their relationship. They believed that together, they were protected from their own natures, they could be “normal”, but the fantasy of living like Clark Kent could never last.

During their final, extended conversation, regret surfaces repeatedly. His question, “Are you calling me a ruthless murderer?” seems less a denial and more a pained query about how she ultimately sees him. His description of the massacre (“I overreacted”) is a chillingly detached admission of his catastrophic emotional failure. His genuine interest in her life during her coma hints at the future they lost. Ultimately, his calm acceptance of death after Beatrix employs the Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique is steeped in this melancholy, a quiet resignation to the consequences of his actions and the tragic trajectory of his love story. He is the saga’s sorrowful king, haunted by the kingdom he himself destroyed.

Beatrix: Victory’s Heavy Toll

And what of The Bride? Having carved her path through Vol. 1 with near-mythic determination, Vol. 2 reveals the woman beneath the warrior, grappling with the emotional weight of her necessary violence. The relentless killer evolves into a more complete and complex figure, marked by sorrow and exhaustion.

The scene in the hotel bathroom after finally killing Bill is pivotal. She doesn’t strike a triumphant pose. She collapses, weeping uncontrollably, repeating “Thank you.” This is more than just relief; it’s the shattering release of years of trauma, grief, and the sheer psychological burden of her quest. It visually confirms the profound cost of achieving her revenge.

Does she regret killing Bill? Likely not his death itself, given his unforgivable actions. But the film allows space for a deeper sorrow. Seeing Bill interact lovingly with their daughter, offers a glimpse of the fractured family life that might have been. Beatrix’s quiet observations suggest a regret not for Bill the monster, but for the lost potential of the connection they once shared, a life stolen by violence, his and, necessarily, hers.

The discovery that B.B. is alive reframes everything. Her rampage wasn’t just punitive; it was restorative, reclaiming her future. This forces Beatrix to confront the seemingly irreconcilable parts of herself: the nurturing mother she longed to be and the lethal killer she had to become. Her journey concludes not with the erasure of her past, but with the challenge of integrating these identities. The Beatrix at the end is a survivor, acutely aware of the price of that survival, forever marked by the sorrowful necessity of her violent path.

Structural and Stylistic Reinforcement

This thematic deepening in Vol. 2 is intrinsically linked to its identity as a separate film from Vol. 1. The changing structure deliberately encourages reflection. The non-linear flashbacks aren’t just exposition; they provide emotional context specific to Vol. 2‘s contemplative mood. The chapter structure, focusing significant time on characters like Budd and Bill, shifts the emphasis from pure plot progression to character study. Most importantly, the pace slows dramatically compared to Vol. 1, allowing for long stretches of dialogue that delve into philosophy, history, and internal states. Unlike the kinetic energy of the first film, Vol. 2 makes you listen, makes you consider the weight behind the words, creating the necessary space for themes like regret to resonate within its own distinct cinematic framework.

Conclusion: Beyond Revenge, A Dual Legacy

To view Kill Bill solely as a singular revenge film, or even just through the lens of Vol. 1, is to miss the profound shift and thematic depth offered by its counterpart. By embracing the complexities of regret, loss, and consequence, Kill Bill: Vol. 2 elevates the entire saga, functioning as a powerful, contemplative film in its own right, as well as a fitting conclusion. This deliberate divergence in tone, style, and focus across the two volumes underscores why they arguably function most powerfully as distinct entities. Vol. 1 provides the kinetic thrill and stylistic fireworks; Vol. 2 offers the resonant emotional payoff and space to absorb the human cost. Appreciating them separately enhances the understanding of the journey from adrenaline-fueled rampage to melancholic reckoning.

Tarantino suggests through Kill Bill Vol. 2 that even the most righteous seeming violence leaves indelible scars, hollowing out perpetrator and survivor alike. The ‘coolness’ of the action, so central to Vol. 1, is haunted in Vol. 2 by the melancholy aftermath. Revisiting Kill Bill in 2025, this focus on the emotional fallout feels especially resonant. In an era increasingly conscious of trauma and the long-term consequences of violence, this exploration of regret offers a richer, more enduring experience than simple admiration for its stylish surface. It remains a potent story about the cycles of violence, the near impossibility of escaping one’s past, and the sorrowful weight carried even by those who win the fight. The Bride gets her revenge, yes, but the silence that follows Bill’s final steps in Vol. 2 echoes not with simple triumph, but with the profound and lingering ache of regret, a feeling best contemplated within the distinct space that the second film provides.