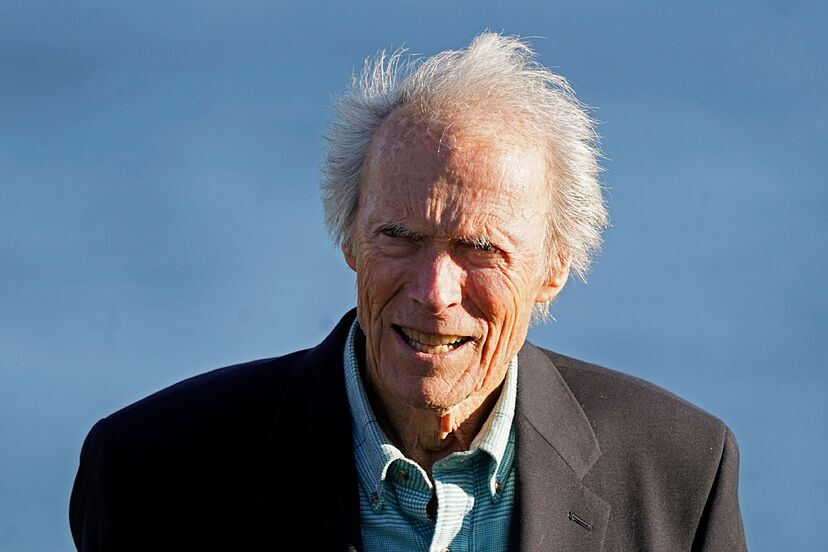

Clint Eastwood turns 95 this week. An almost unfathomable milestone for a career that feels as elemental as the Hollywood sign itself, and as raw and unforgiving as a high-noon standoff. To attempt to chart Eastwood’s seven decades in cinema is to review a landscape of shifting American identity, and a relentless, career-long wrestling match with American masculinity.

Such a panoramic career, one that encompasses not only genre-defining Westerns and iconic crime thrillers but also unexpected diversions like the musical, Paint Your Wagon (1969), sensitive dramas such as The Bridges of Madison County (1995), and acclaimed directorial achievements in which his on-screen persona is either absent or secondary, like Mystic River (2003) or the paired historical statements of Flags of Our Fathers (2006) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006). A lengthy and diverse career like his defies exhaustive analysis in a single essay. To do justice to its sweep would require an entire book (or more!).

Our approach, therefore, is necessarily selective, focusing on a curated collection of landmark films. These are not merely personal favorites; they stand as crucial signposts, embodying distinct eras in Eastwood’s evolution while offering the most potent lens through which to examine his profound and enduring engagement with that central theme of American manhood. Other pictures, like the revisionist Western. The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), certainly echo these concerns and mark important career junctures, but the films we will explore serve as the clearest crucibles for our specific thematic fire.

Through these carefully chosen examples, we see how Eastwood – star, auteur, enigma – hasn’t just mirrored ideals of manhood, but actively forged, interrogated, and sometimes shattered them. From sun-baked mesas to rain-slicked city streets, his silhouette casts a long, often troubling, shadow over what it meant, and means, to be a man in a transformative American century.

Era 1: Forging the Frontier Myth – The Stoic Individualist (c. 1964-1971)

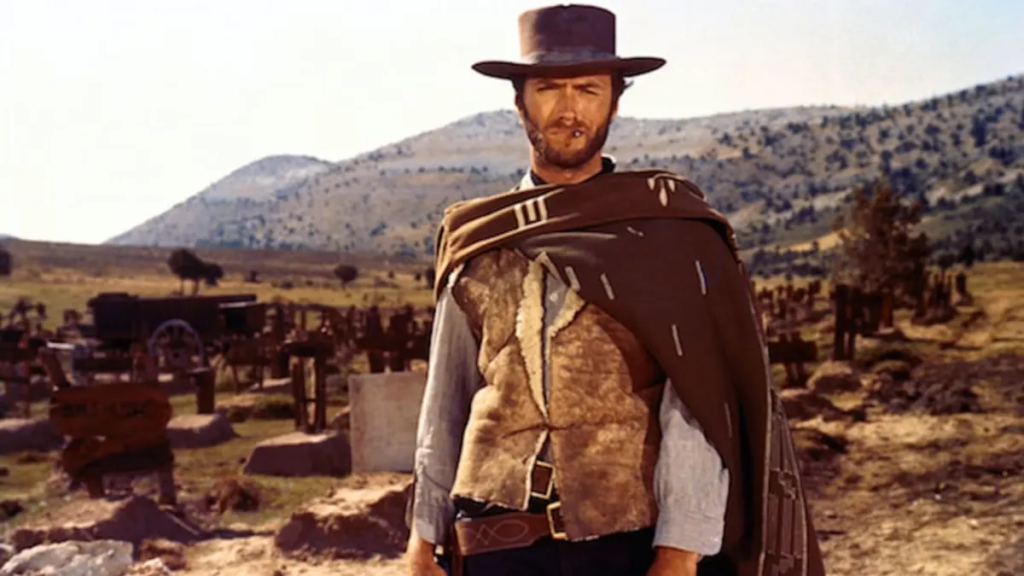

(Focus Film: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly)

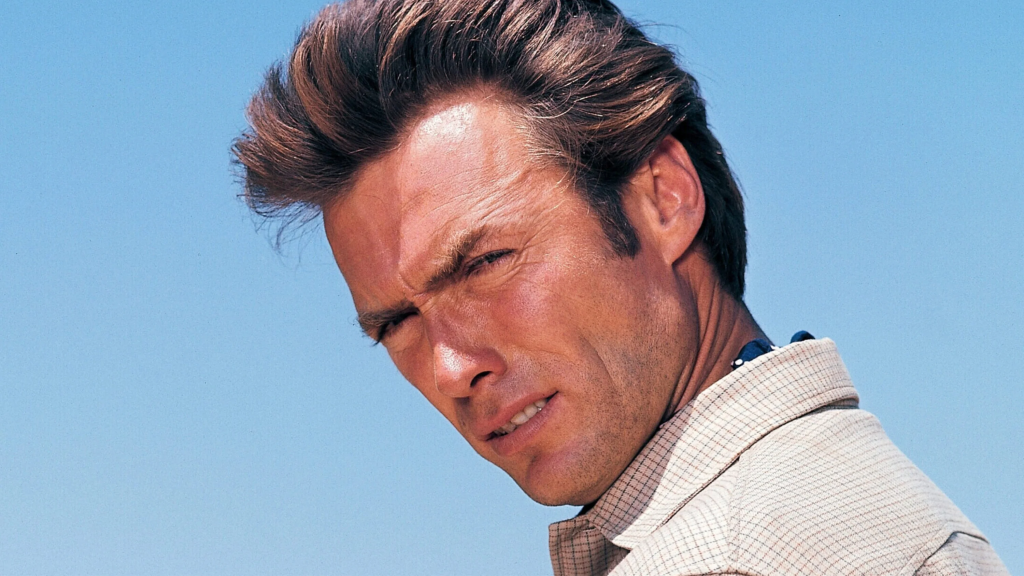

The squint. The poncho. The cheroot. The name on everyone’s lips, though rarely spoken by the man himself: Blondie. When Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly exploded onto screens in 1966, it wasn’t just a film, it was a cultural detonation. Ennio Morricone’s unforgettable score became the anthem for a new kind of Western, and Clint Eastwood, with his minimalist cool, became its face. This was where the Eastwood persona – laconic, lethal, morally ambiguous – was seared into the global cinematic consciousness, launching a new, potent vision of American masculinity onto the world stage.

Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns weren’t just horse operas; they were audacious, operatic revisions of a fading Hollywood dream. As American-made Westerns lost their footing, these Italian born epics, shot through with a cynical verve, offered a radical alternative. Critics and scholars would later fill volumes dissecting Leone’s revolutionary style and Eastwood’s symbiotic role within it, but the immediate impact was visceral: the Western landscape suddenly became alien, dangerous, and thrillingly unpredictable.

At the heart of this new frontier was the anti-hero. American cinema had certainly flirted with morally grey protagonists before – Bogart’s world-weary PIs or Brando’s brooding rebels come to mind. Even in Westerns, complex figures were emerging to challenge the polished hero stereotype: think of those in Anthony Mann’s psychological dramas, John Ford’s The Searchers, and not least, Paul Newman as the memorably cynical Hud Bannon.

Eastwood’s ‘Man with No Name’ was a different creature altogether. His compass, if he had one, spun wildly, usually settling on self-interest. Eastwood’s genius was his stillness, his ability to command the frame with an almost Zen-like economy of expression. This wasn’t the garrulous hero of yore; this was a man who understood that in a brutal world, silence, punctuated by sudden, decisive violence, was the ultimate currency. This, then, was the new masculine cool.

The Dollars Trilogy made Eastwood a global phenomenon. He became, as some would say, the inheritor of John Wayne’s crown, but this new king of American masculinity ruled a starkly different kind of kingdom: cynical, solitary, and forged in an international crucible. The stoic, self-reliant figure he etched here would become the granite foundation of a career spent exploring, and often subverting, that very image.

Era 2: Urban Justice & Assertive Masculinity: The Actor Takes Control (c. 1971-1980s)

(Focus Films: Dirty Harry; Play Misty for Me)

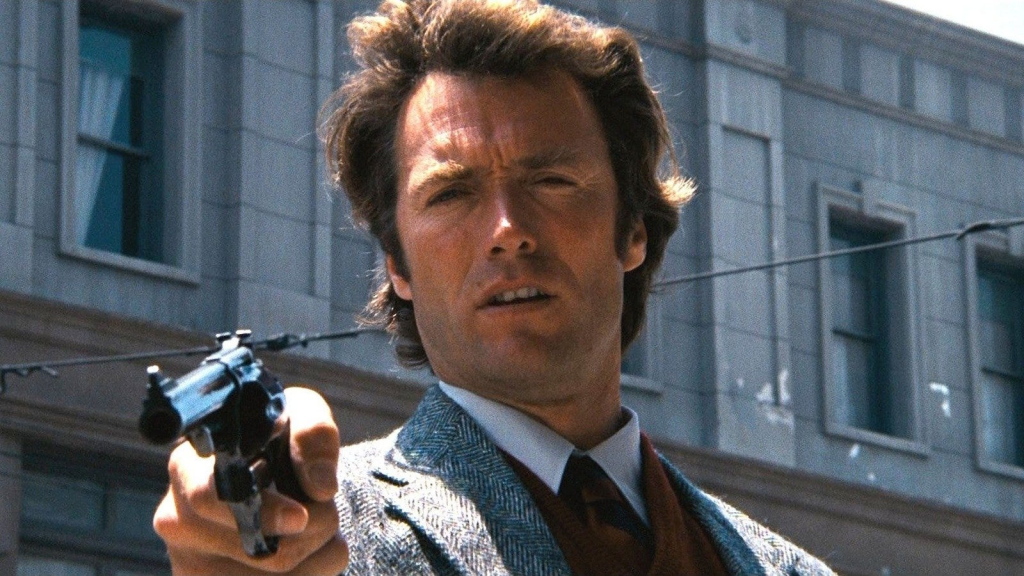

“Do I feel lucky?” The question, delivered with a .44 Magnum’s cold authority, echoed far beyond the crime-ridden streets of Don Siegel’s 1971 San Francisco. Dirty Harry was more than a hit; it was a cultural flashpoint. Inspector Harry Callahan, Eastwood’s new avatar, strode into a landscape of societal anxiety, a figure worlds away from the taciturn Blondie, yet forged from the same steel. Callahan’s violence wasn’t for gold; it was a political statement, a brutal answer to what the film presented as a city unraveling under the perceived excesses of counter culture.

Siegel’s San Francisco is a battleground where liberal pieties have failed, crying out for Callahan’s brand of “common sense” justice. It’s a vision whose confrontational politics would resonate with a Nixonian “silent majority” and, startlingly, prefigure the culture war talking points of decades to come. But the film’s power, and its enduring controversy, lies in its uncomfortable embrace of its flawed hero. Callahan is bigoted, insubordinate, and his methods are a civil libertarian’s nightmare. Yet the film dares you to root for him, a provocative stance that forces a confrontation with the audience’s own hunger for order, however ruthlessly imposed. This was masculinity as a blunt instrument, contemptuous of bureaucracy, unleashed to cleanse the streets.

This raw, confrontational cinema was pure New Hollywood in its audacity, even as its politics leaned right. And at its nucleus was Eastwood, now a bona fide superstar. Dirty Harry didn’t just cement another iconic persona; it was produced by his own Malpaso Company, a clear signal of his intent to sculpt his own destiny. He was no longer just the Man with No Name; he was rapidly becoming the Man in Charge, a pivotal move towards the actor-auteur status that would define his later career.

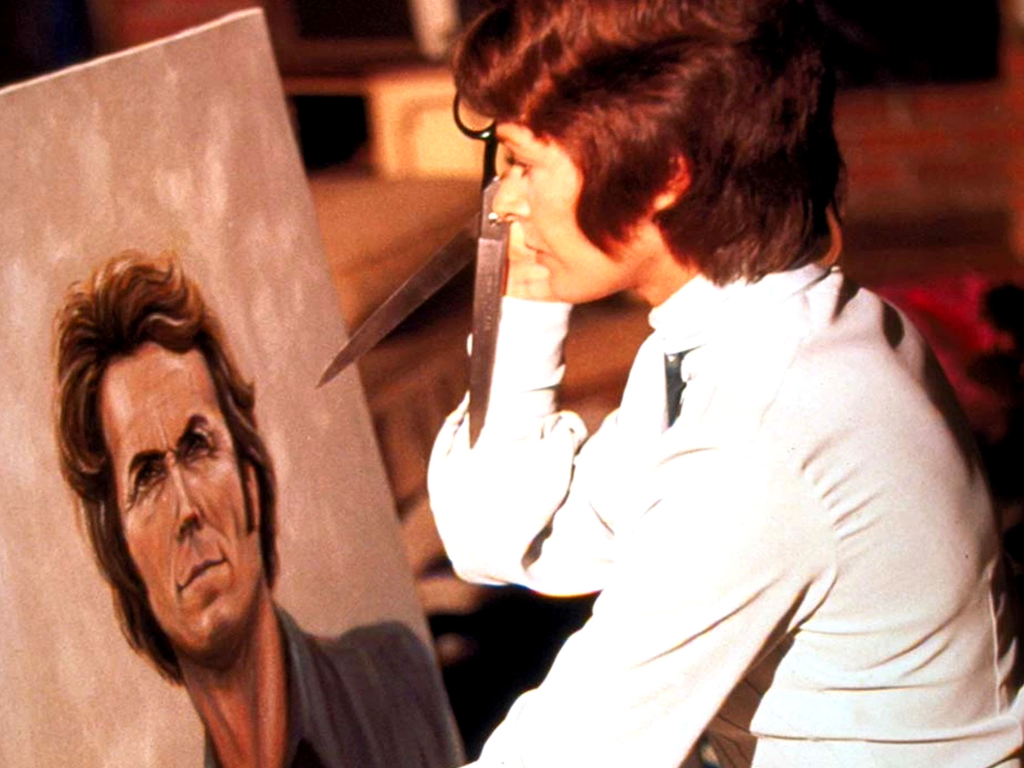

And 1971 wasn’t just the year of Harry Callahan’s furious street justice; it was the year Clint Eastwood, with audacious quiet, first stepped behind the camera. Play Misty for Me, his directorial debut, is far more than a curious footnote; it’s a surprisingly taut and unsettling psychological thriller that immediately telegraphed ambitions beyond the confines of action stardom. Here, Eastwood the actor immerses himself in the cool jazz hues of Carmel, playing Dave Garver, a charismatic late-night DJ whose smooth baritone and freewheeling lifestyle are a world away from the violent frontiers he usually patrolled. Yet, even in this seemingly more relaxed milieu, Eastwood the director begins to probe a certain kind of contemporary male identity, one whose casual confidence perhaps masks a deeper unpreparedness for the darker currents of human connection.

What remains striking about Play Misty for Me is its unnerving prescience, an early tremor of the ‘stalker thriller’ subgenre that would become a cinematic staple decades later. Jessica Walter’s Evelyn Draper, the devoted fan whose initial phone-in request spirals into a terrifying fixation, is not merely a spurned lover but a figure of escalating, unpindownable menace. The film charts this descent with a chilling patience, suggesting Eastwood, even as a freshman director, possessed an instinct for the primal fear that arises when intimacy sours into obsession, and control is wrested away. For an Eastwood protagonist, it’s a novel form of vulnerability; not the threat of a bullet, but the insidious creep of psychological warfare, where the domestic space becomes a battleground.

As a director, Eastwood already sketches the outlines of the efficient, atmospheric style that would become his signature. The breezy Carmel coastline, a sun-dappled idyll, is artfully juxtaposed with the claustrophobia of Evelyn’s obsession, the scenic beauty offering a stark counterpoint to the film’s increasingly dark heart. While bearing some hallmarks of its era’s studio thrillers, there’s a raw, discomfiting edge to the central conflict, particularly in Walter’s ferociously committed performance, that still has the power to disturb. It’s a deliberately uncomfortable journey, suggesting an early authorial interest in pushing audience boundaries, albeit through the shadowy corridors of desire rather than the explicit politics of Callahan’s San Francisco.

Thematically, Play Misty for Me offers a fascinating counter-narrative to the assertive, often righteous masculinity Eastwood was simultaneously embodying elsewhere. Dave Garver, for all his laid-back charm and professional cool, is a man whose lifestyle renders him unexpectedly vulnerable. There’s a subtle, almost cautionary exploration here of the consequences that can follow when casual connections ignite something far more volatile, a theme of male misjudgment meeting female pathology that the film navigates with a tense focus. It’s also a compelling early glimpse into Eastwood’s career-long fascination with obsession, the fragility of sanity, and the often-perilous dance of human relationships, themes that would echo in more complex, varied forms in his later directorial work.

While it may not possess the overt genre revisionism of Unforgiven or the stark iconic power of his gun-wielding figures, Play Misty for Me stands as a crucial, surprisingly assured debut. It’s Eastwood taking the directorial reins with confidence, proving his mettle in a new arena, and demonstrating an immediate grasp of suspense mechanics. More than that, it reveals an artist already keen to explore the psychological landscapes beneath the action, adding a vital, more introspective layer to that pivotal year of 1971 and signaling the multifaceted career that was to come. The one-two punch of Dirty Harry and this accomplished first film as director truly announced Eastwood as a defining force, shaping his narratives on both sides of the camera.

Era 3: Deconstructing the Hero, Interrogating American Manhood (c. Late 1980s-Mid 2000s)

(Focus Films: Unforgiven; Million Dollar Baby)

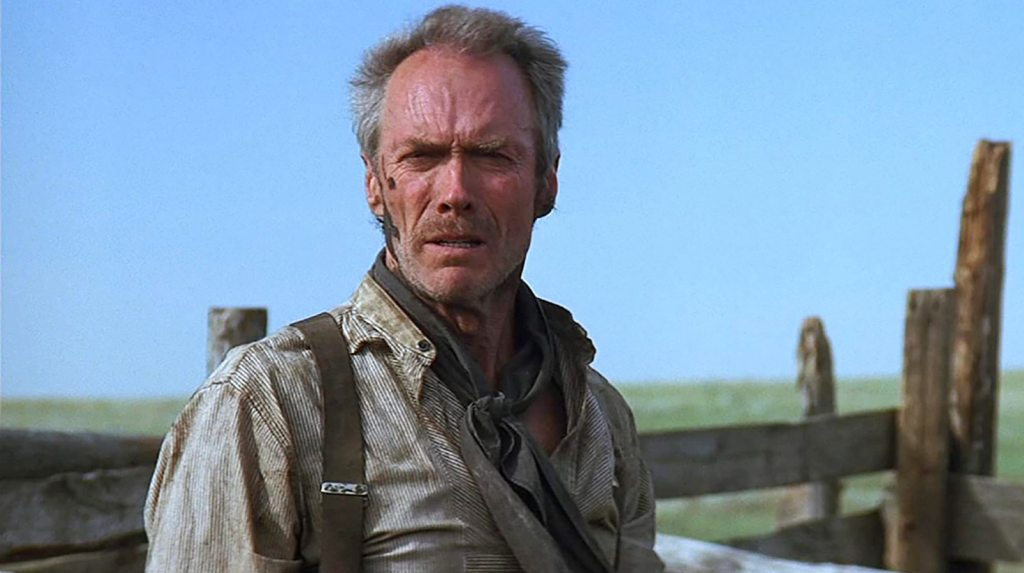

Then came Unforgiven. If Dirty Harry codified the Eastwood persona, this 1992 masterwork saw him hold that very image up to the harshest light, then shatter it. Here was Eastwood, the Western icon, returning to the genre not to polish the myth, but to bury it with full, brutal honors. This wasn’t just a great film; it was a reckoning. The moment Eastwood, the accomplished director, fully merged with Eastwood, the screen legend, to create something profound. The Oscars for Best Picture and Director weren’t just accolades; they were an industry acknowledging an artist who had transcended his origins.

William Munny, the retired pig farmer and former killer, is the ghost of Blondie, stripped of all romance. The weight of regret hangs heavier than any gun belt. His quietness isn’t cool detachment; it’s the weariness of a soul that knows the true cost of violence. When Munny is drawn back into that world, the violence is clumsy, ugly, and devoid of glory. Unforgiven is an elegy for the Western, a meditation on the brutal reality underpinning the frontier legend, and perhaps a reflection of a post-Cold War America forced to confront the consequences of its own violent mythologies. Gene Hackman’s Little Bill Daggett, a man who perverts justice with sadistic glee, provides the perfect corrupt counterpoint to Munny’s tortured path.

The critical acclaim for Unforgiven opened a new chapter. Eastwood was now a revered American auteur. He followed it with films that continued to explore the complexities of character and morality, none more devastatingly than Million Dollar Baby (2004).

Here, as grizzled trainer Frankie Dunn, Eastwood again inhabited an aging figure confronting his own limitations. The film’s boxing narrative echoes Rocky but veers into far darker, quintessentially Eastwoodian territory in its final act. Frankie’s initial reluctance to train Maggie Fitzgerald, his gruff exterior, sets the stage for a relationship that slowly thaws his hardened masculinity, revealing a profound, paternal vulnerability. His understated performance, where a flicker of tenderness speaks volumes, is a testament to his mastery. And again, the film’s tragic core, its refusal of easy sentiment, resonated in an America grappling with its own sense of identity, earning Eastwood another pair of Oscars and cementing his status as a filmmaker unafraid of life’s hardest questions.

Era 4: The Anachronistic Man – American Chronicles and Enduring Legacies (c. Mid 2000s-Present)

(Focus Film: Gran Torino)

By 2008, Clint Eastwood was an institution, yet Gran Torino proved he could still ignite a cultural firestorm. As Walt Kowalski, a widowed Korean War vet rattling around his changing Detroit neighborhood, Eastwood presented one of his most potent late-career characters: the American man as an anachronism. Walt is a walking monument to a bygone era, his beloved Ford Gran Torino a gleaming relic of a time when America made things, and men, it seemed to Walt, were made differently. His casual bigotry, his growling contempt for the perceived decay of his world – from his “pampered” grandchildren to the Hmong family who move in next door – is Eastwood holding up a mirror to a raw, uncomfortable part of the American psyche.

The film’s narrative charts Walt’s grudging path to redemption, as he forms an unlikely bond with Thao, the Hmong teenager he initially despises. This mentorship echoes themes from Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby, yet for all its effectiveness, Gran Torino treads somewhat familiar ground, perhaps sidestepping a deeper dive into the socio-economic despair that shaped Walt’s bitterness. But what remains undeniable is the sheer force of Eastwood on screen. At 78, he is utterly compelling as Walt, physically imposing, a man whose self-reliance is etched into every line on his face. He is the silent strength, the ingrained competence that defined his characters for decades. Walt Kowalski became another indelible Eastwood figure, a man wrestling with his own obsolescence and finding one last, defiant act of meaning, connecting powerfully with audiences worldwide.

Clint Eastwood at 95: the career itself feels like a sprawling American epic. More than just an actor who endured or a director who achieved acclaim, Eastwood has been a constant, often challenging, presence in our collective imagination, his silhouette synonymous with a certain kind of American man. Yet, as we’ve seen, that “certain kind” has never been static. From the mythic frontiersman to the urban vigilante, from the haunted killer confronting his past to the aging lion roaring against the dying of the light, his films have provided a running commentary on American masculinity, its power, its pathologies, its pain, and its potential for unexpected grace.

The journey through these eras, marked by films like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Dirty Harry, Unforgiven, Million Dollar Baby, and Gran Torino, reveals an artist unafraid to engage with, and ultimately deconstruct, the very archetypes that made him a star. Through Malpaso, his singular vision found its way to the screen. His directorial style, lean and direct, mirrored the men he often portrayed: no fuss, all impact.

It must also be noted that Eastwood’s own distinct, often conservative and libertarian inflected worldview has undeniably shaped his cinematic output and public persona. This perspective, sometimes lauded, occasionally divisive, can be felt in the rugged individualism and uncompromising outlook of many of his characters.

His legacy, then, isn’t just in the iconography or the awards. It’s in the conversations his films demand, the uncomfortable truths they often tell about violence, justice, and the often-fraught quest for individual integrity. Clint Eastwood hasn’t just made movies; he’s held an unflinching gaze on the American soul, and in doing so, has crafted a body of work as vital and volatile as the nation itself.