Director: Charlie Chaplin

Writer: Charlie Chaplin

Stars: Charlie Chaplin, Mack Swain, Tom Murray

Synopsis: A prospector goes to the Klondike during the 1890s gold rush in hopes of making his fortune, and is smitten with a girl he sees in a dance hall.

To a generation accustomed to the grand-scale, cerebral blockbusters of directors like Christopher Nolan, the idea of a silent, black-and-white comedy from 1925 might suggest something quaint or primitive. Yet Charlie Chaplin in his prime was a filmmaker with every bit of Nolan’s ambition, technical command, and thematic audacity. By 1925, Chaplin was more than a star; he was a global phenomenon who wielded complete creative control through his own studio, United Artists. He was a writer, director, producer, and composer who built vast sets, marshalled hundreds of extras, and pushed the boundaries of the medium to tell complex, often deeply personal stories. It is this context that makes The Gold Rush so vital. Made during the Roaring Twenties, it reveals itself not as light entertainment, but as Chaplin’s foundational political text, the moment he first weaponized his beloved Tramp to systematically deconstruct the great American myth of rugged individualism.

The key to this audacious critique is, of course, the Tramp himself. By 1925, Chaplin’s on-screen persona was a global icon, a figure of instant familiarity and empathy. In placing this established character into the vast, indifferent wilderness of the Klondike, Chaplin bypasses the need for complex backstory, instead presenting us with a universal surrogate. He is everyman, stripped of voice and status, defined only by his poverty and his hope. While contemporaries like Buster Keaton used their bodies to create breathtaking physical spectacle, Chaplin, operating with total creative freedom, used his to generate political meaning. His diminutive figure, perpetually shuffling with a determined optimism against the epic, snow-swept landscapes, becomes a potent symbol of human fragility in the face of a cruel system.

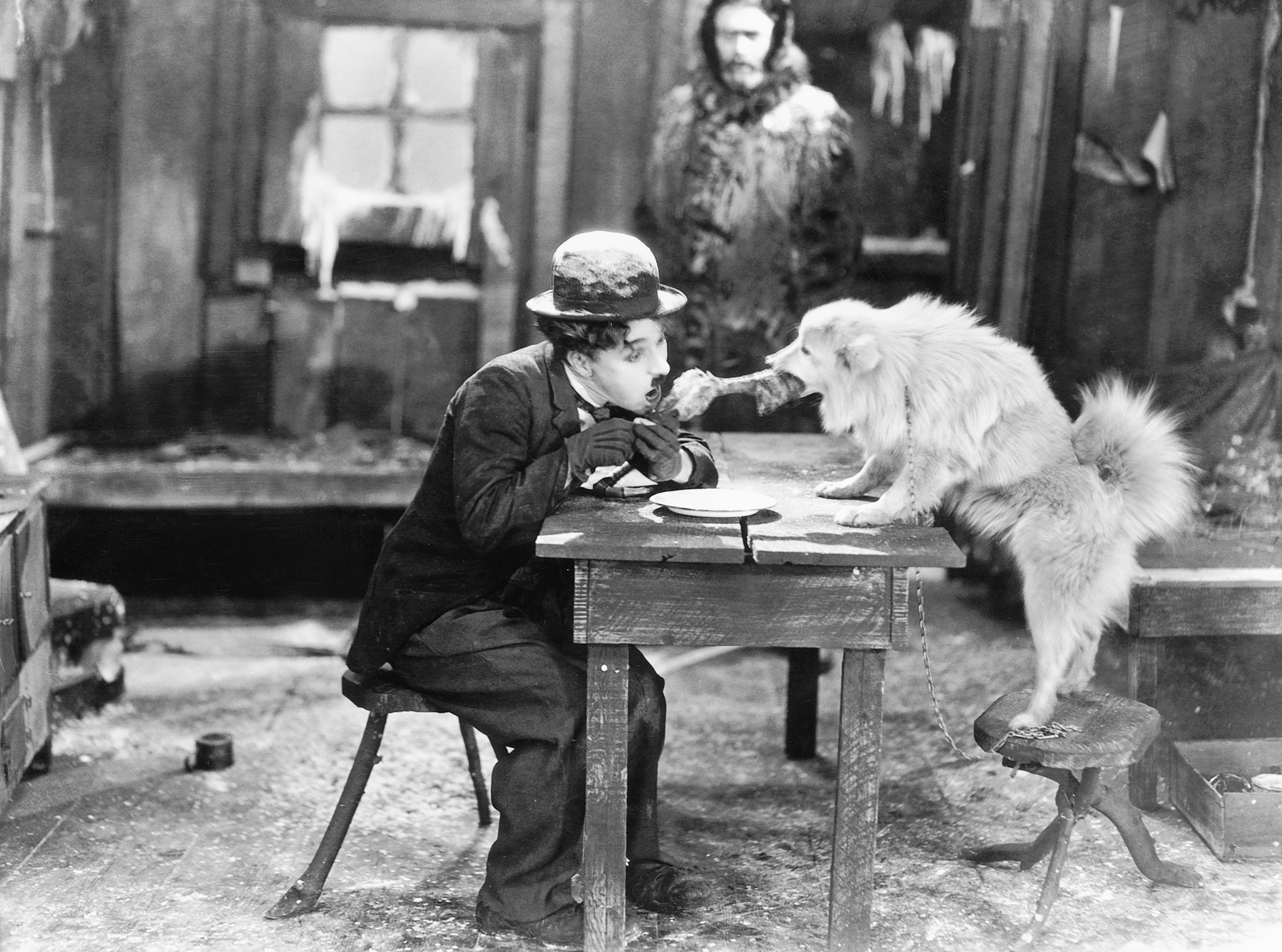

This critique is embedded in the fabric of the film’s narrative, or lack thereof. The Gold Rush feels disjointed, a collection of high-stakes vignettes thinly connected by the titular quest. But what could be viewed as a structural weakness is, in fact, the film’s sharpest critical tool. The official idea of the American Dream is a coherent, linear journey of upward progress. Chaplin presents the reality as a series of chaotic, desperate episodes, arguing that for the common man, survival under capitalism is not a story, but a disjointed and precarious series of crises. Each set-piece functions as a grimly comic parable. The infamous boot-eating scene transcends a simple gag about hunger; it becomes a bitter satire on commodification, showing men trying to extract sustenance from the very apparatus of their worn-out labor.

Nowhere is this blend of pathos and politics more potent than in the celebrated New Year’s Eve sequence. Having naively invited the dance-hall girls to his cabin, the Tramp prepares a meager but heartfelt celebration. As he waits, he falls asleep and dreams of hosting the perfect party, charming his guests with the delightful “Oceana Roll” dance. The fantasy is pure Chaplin magic; graceful, inventive, and joyous. Yet the cut back to reality is a moment of profound cruelty. He is alone; the girls have forgotten him, mocking his very existence. This is not simply a moment of personal heartbreak; it is a damning indictment of a society in which sincerity and effort are worthless without social or economic capital. It’s a direct attack on the comforting notion that good intentions are their own reward.

The film’s most iconic sequence, the cabin teetering on the edge of a cliff, serves as the ultimate metaphor for this precarity. It is a masterful piece of suspense, a physical representation of the prospector’s entire existence, balanced on a knife-edge between illusory safety and total oblivion. Every shift in weight, every creak of the floorboards, speaks to the lack of any solid ground beneath the feet of those chasing fortune. Even the film’s ostensibly happy ending, in which the Tramp and his partner stumble upon a “mountain of gold” and become millionaires, feels laced with a deep cynicism. After an entire film demonstrating the futility and brutality of the system, this sudden, miraculous resolution feels less like a heartfelt conclusion and more like a sardonic concession to genre, a final joke suggesting that the only way to truly win is through sheer, dumb luck—a lottery ticket, not a reward for merit.

Indeed, the sheer boldness of Chaplin’s film raises a critical question about his legacy. While modern filmmakers certainly engage with politics, it is often through the lens of other genres, the cerebral, high-concept spectacle of Christopher Nolan or the social horror of Jordan Peele. The kind of audacious, mainstream comedy that is also a direct and cynical political assault remains a profound rarity. One has to look to savage outliers, like the scabrous puppetry of Team America: World Police, to find a true successor to the spirit of a film like Dr. Strangelove or The Gold Rush. Perhaps the reason for this scarcity lies in Chaplin’s own story. His eventual exile from the United States during the McCarthy era stands as a stark reminder of the potential cost for a mainstream entertainer who dares to embed such a potent critique of American ideology into their work.

Seen through this lens, The Gold Rush is the essential proving ground for the masterpieces that would follow. Without the trial run of using the Tramp to critique the false promise of the Klondike, there could be no Modern Times to satirise the industrial production line, nor a Great Dictator to confront the horrors of fascism. It is here that Chaplin discovered the full potential of his art form. The film’s enduring genius lies not just in its ability to make us laugh, but in its courage to suggest that the promise of fortune for all was a bleak and hollow joke, a punchline for which its creator would eventually pay a heavy price.