Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Writer: Francis Ford Coppola

Stars: Gene Hackman, John Cazale, Harrison Ford

Synopsis: Harry Caul, a meticulous and intensely private surveillance expert, is hired to record a conversation between a young couple. As he painstakingly pieces together the fragmented recording, he becomes increasingly obsessed and guilt-ridden, believing he may have uncovered a potential murder plot. His professional detachment crumbles into paranoia as he grapples with the moral implications of his work and the ambiguity of what he has heard, leading him to question everything and everyone around him.

Francis Ford Coppola’s staggering run in the 1970s – The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Apocalypse Now often overshadows the quieter, more introspective film nestled right in the middle: The Conversation (1974). Yet, revisiting this paranoid thriller today reveals it as not just a product of its Watergate-era anxieties, but a chillingly prescient and masterfully crafted character study with themes that echo louder than ever in our hyper-surveilled world. It’s a film that leaves you feeling both tense and deeply thoughtful, grappling with ambiguity long after the credits roll.

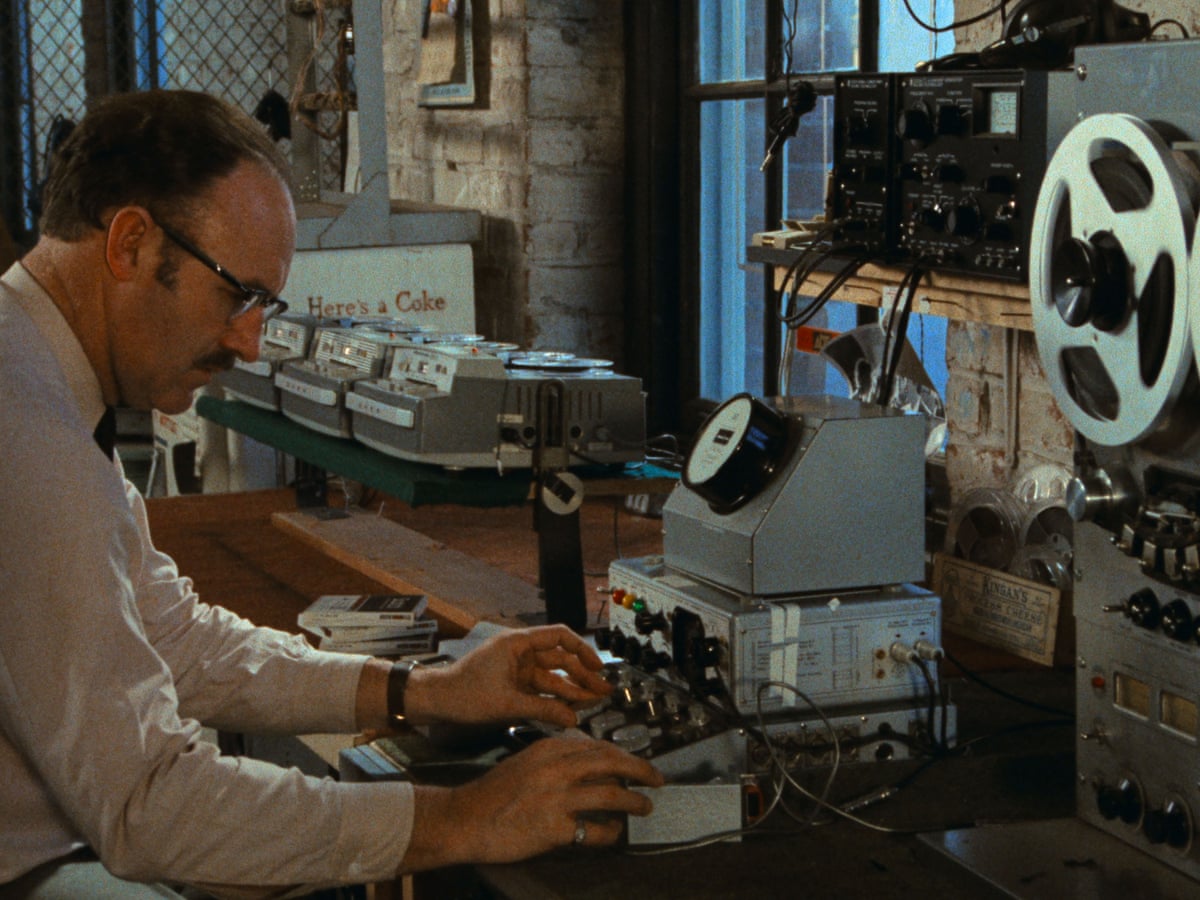

At its heart is Harry Caul, arguably Gene Hackman’s finest, most understated performance. In the wake of Hackman’s recent passing, revisiting his portrayal of Caul feels particularly poignant. This isn’t the bombastic Popeye Doyle or Royal Tenenbaum; this is a deeply internalized study of a man at the absolute peak of his clandestine profession – audio surveillance – yet profoundly tormented by its moral implications. Hackman embodies Caul’s meticulousness, his crippling social awkwardness, and the gnawing guilt stemming from a past job gone wrong. He’s a virtuoso haunted by his own expertise. Weathered and competent, yet unraveling under the weight of his conscience. We see glimpses of pride in his craft, particularly during a revealing party scene in his workshop fortress, but mostly we witness a man desperately seeking detachment, only to be drawn inexorably into the lives he records.

The plot, like Caul himself, operates with a slow-burn intensity. Tasked with recording a seemingly innocuous conversation between a young couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) in a busy San Francisco square, Caul becomes obsessed with deciphering its meaning and potential consequences. Coppola masterfully uses ambiguity, is Caul uncovering a murder plot, or is his paranoia projecting sinister interpretations onto fragmented phrases? The film refuses easy answers, layering Caul’s escalating anxiety onto the narrative, forcing the viewer to question what is real versus what is perceived. This deliberate pacing and refusal to spell everything out are central to the film’s cumulative impact.

Released in the shadow of Watergate, The Conversation was undeniably a commentary on burgeoning surveillance technology and governmental overreach. Yet, its exploration of privacy, guilt, and the dehumanizing potential of technology feels startlingly contemporary. Coppola seemed to anticipate the anxieties of our modern surveillance capitalism. The tech may look quaintly analogue now, but the core dilemma – the trade-off between technological capability and personal privacy, the unease with relentless progress – remains potent. One can easily imagine a modern Caul as a conflicted Silicon Valley engineer, eschewing the very tools he helps create.

Crucially, the film’s power relies heavily on its groundbreaking sound design, orchestrated by Walter Murch, and David Shire’s unsettling score. Sound isn’t just accompaniment; it is the subject. The repeated playback of the titular recording, gradually revealing different layers and potential meanings, draws the viewer directly into Caul’s obsessive analysis. Shire’s piano-led score, balancing melancholy melody with jarring, discordant notes, perfectly mirrors Caul’s fractured psyche and amplifies the pervasive sense of unease. Watching with headphones truly immerses one in the film’s meticulously crafted soundscape – a debt clearly owed by modern scores like that of Severance.

While The Godfather films and Apocalypse Now sprawl with epic grandeur, Coppola adopts a more austere, claustrophobic approach here. The focus is tight, the mood oppressive. Much of the film unfolds in confined spaces – Caul’s workshop, anonymous hotel rooms, crowded convention floors enhancing the sense of isolation and paranoia. It’s a testament to Coppola’s directorial range, proving he could craft a taut, character-driven psychological thriller as effectively as a sprawling crime epic.

Though Hackman dominates, the supporting cast is superb. John Cazale, in another tragically brief but memorable turn, brings a nervous energy to Caul’s assistant Stan. Their dynamic subtly mirrors Harry’s own internal battle: Harry admonishes Stan for his curiosity about their subjects’ lives, a projection of the very impulses Harry struggles to suppress within himself, attempting to convince himself as much as his colleague. A young, almost unrecognizably sinister Harrison Ford makes an impact in a small but pivotal role, and Allen Garfield provides a contrasting note of sleazy professional bravado as competitor and counterpoint, Bernie Moran.

The Conversation doesn’t offer neat resolutions. Its famous ending is a haunting tableau of paranoia consuming itself, leaving the audience, like Caul, surrounded by questions. It’s a film that demands reflection, provoking debate decades after its release. In its meticulous craft, its profound themes, and its unforgettable central performance, The Conversation remains an essential, deeply unsettling masterpiece – a quiet film whose echoes continue to reverberate powerfully.