When I made a comment about Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun on Twitter (I’m sorry, I will always call it that), I never dreamt that I would be here writing an actual essay on it. But I’m grateful to those who replied asking for it. Aftersun is one of the very best films of the decade, and I’m eager to dive into why the scene in question is so profoundly moving. For those who are confused, I replied to a prompt asking for the “best shot” of the 2020s so far, and my response was this image:

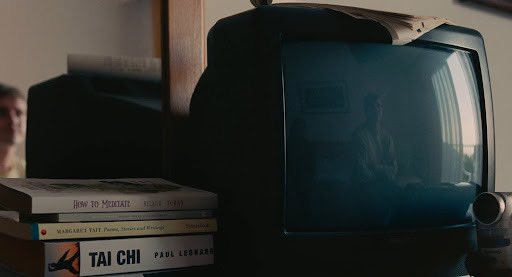

I can (perhaps ironically) barely articulate the devastating effect this had on me when I first saw Wells’ masterpiece. Aftersun is a deeply poignant exploration of memory, nostalgia, and the imperceptible distance between past and present. The film intricately weaves together fragments of recollection to present an emotionally resonant father-daughter relationship. In a film full of evocative scenes, there is one in particular (captured in the still above) that stands out. It takes place in a dimly lit hotel room where an old CRT television, a few books, and a reflection on the TV screen render some of the most stunning visual storytelling of the last decade. This scene encapsulates Aftersun’s broader themes of memory, loss, and the extensive influence of melancholy.

Before we get into the hotel scene we need to set up some vital context. A crucial layer of Aftersun’s structure is its framing device—Older Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), a clear stand-in for Wells herself, is a conduit for this story as it unfolds. The majority of the film operates as a flashback, a deeply personal act of reflection as older Sophie revisits her childhood memories and attempts to reconcile them.

She has no narrative arc. She serves no other purpose. She is exclusively a vessel through which the past is explored. This will become very important as we explore the symbolism and emotion of the hotel scene.

With that foundation set, let’s go back to young Sophie (Frankie Corio) and the vacation she is on with her father, Calum (Paul Mescal). Before we return to the hotel, it’s worth emphasizing that Wells features a few great moments previously that also tap into the film’s thematic underbelly to help pave the way. Specifically, I’m thinking of the scene where Sophie is first toying with her camera.

Or this intensely heartfelt shot with Sophie sitting on a chair up against the wall on one side of the frame, in contrast to her father emotionally unraveling in the bathroom on the other side of the frame. Coupled with the hotel scene we’re about to discuss, and the film’s most iconic moment at the end, this is an image that will instantly come to mind for many viewers with Aftersun.

Or, in what might be my second favorite scene of the film, there’s a powerful moment in which Sophie is laying down on the bed in the hotel (these hotel scenes just murder me) that are intercut with her father once again in the bathroom, this time brushing his teeth. Sophie mentions that she feels down, and after Calum asks what she means, Sophie begins this incredible monologue talking about that feeling of coming home after a great day and feeling drained. So tired, in fact, that you feel like your bones don’t work. The dialogue itself here is astute, but it’s what Wells does with the camera that I find even more captivating. At the beginning of the scene, Sophie is on the bed with the camera right side up. When the moment intercuts to Calum, his reflection is in the mirror but upside down. However, as Sophie begins her stirring speech, the roles become reversed as the camera is pointed at a mirror reflecting Sophie on the bed, but soon pans to a despondent Calum who is both in frame and reflected at the audience in the bathroom mirror. The moment ends with Calum spitting at his reflection in the mirror in disgust with himself.

All of these moments immaculately pave the way for the hotel scene about halfway through the film. Let’s first talk about composition. It’s a slightly low-angle, stationary shot with the camera pointed at the TV in the hotel room, alongside a few books on the left side of the frame. Sophie has once again hooked up her camera to the TV, so we can see what she’s filming in real time. At first, it’s quite playful as she’s pointing out the size differences between their beds. She then aims the camera at Calum and he starts a little dance that embarrasses her. The dynamic in those early moments is wonderfully charming and deeply relatable to both parents and sons and daughters.

But then she goes to interview her father, and she states that she’s celebrating her 11th birthday, before asking him about what he thought his life would be like when he was 11. To which he becomes despondent once again and asks Sophie to turn off the camera. She hesitates, but obliges him. Wells, however, doesn’t cut and continues to linger on the TV, which is now blank, although we can still see Sophie and Calum in the reflection of the glass on the TV.

As an aside, I love the line where Sophie says, “fine, I’ll record it in my mind camera.” It’s an endearing moment and the delivery by Corio is perfect. It simultaneously speaks to the nucleus of Aftersun as it relates to memory. We’re always recording in our mind camera. There’s a never-ending roll of film in our brains that captures the beauty of life for us to look back on as we get older. It’s kind of funny how an innocuous line of dialogue in the middle of a deeply layered sequence like the hotel scene can carry so much thematic weight. Especially when the main intent of the line is to offer a brief moment of levity.

Anyway, getting back to the interview, Sophie asks Calum, “what did you do for your 11th birthday?” Calum goes on to tell the heartbreaking story that no one remembered that it was his birthday. Eventually he told his mom, she got angry and made his father go out and buy him a toy. Calum does his best to shrug off the moment, stoically looking out the window, as he tells Sophie that his toy of choice was a red phone. It’s quietly devastating. Even in the moment, Sophie denotes that his answer is “deep.”

This is why older Sophie, as a conduit, matters to this moment. This is a memory that would have likely carried weight with her regardless, given the interaction between the two and Calum being vulnerable with her by telling that story. But, of course, this memory would be even more impactful as she grows up and recognizes the connection between Calum’s sadness and what we see at the end of the film (his fate). There is something profound, almost transcendent, about Wells using art in this way. Creating a character who is looking back at the footage that she captured when she was a child and reflecting back on it enables her (and us) to explore it in a different way. All of this occurs while symbolically using reflection as narrative and thematic tool to redolently articulate the crossroads of your love of film and the deep memories you had of your father.

The passion and sophistication by Wells here is hard to fathom from a first-time filmmaker. Aftersun is about, in a word, reflection. And in this scene where reflection is the nucleus. Yes, it’s Sophie reflecting back on this memory. However, because of Sophie’s question about his birthday, Calum is forced to reflect back on, and wrestle with, a memory that clearly compounded his melancholy. Watching Calum and Sophie’s literal reflection, on a blank, stark TV screen, in an isolated hotel room, isn’t just potent symbolism. The emotional pathos underneath is a volcano erupting.

The framing of the shot is obviously deliberate, with the old television screen, dark and reflective, functioning as a metaphorical and literal portal into memory. The reflection of Calum on the TV screen is ghostly and fragmented, emphasizing his absence both in the present moment and, as the film suggests, in the future. By positioning the father as an apparition within a technological relic, Wells underscores the impermanence of both memory and physical presence. It’s the perfect cypher for how memory often works in our lives.

As I noted earlier, it isn’t just this scene, it’s pretty much how Wells shoots Aftersun at large. Outside of the examples above, you could consider certain close-ups on body parts, parasailers as they drift by, reflections off the water, or singular objects that have some sort of meaning (a polaroid that is beginning to develop, for example). All of these visuals poignantly tap into Sophie’s relationship with her father because in every one of these instances, Wells cuts before we see them fully formed. That’s the brilliance of the cinematography (from Gregory Oke) and editing (from Blair McClendon) in Aftersun. Together they reinforce the love between Sophie and Calum, but also how fractured they are as well.

Memory is complicated and can often be unreliable. You don’t always have the pieces. By capturing Calum through a reflection rather than directly, the film visually manifests how memories are often distorted, incomplete, or muddled by emotion. The TV screen, which typically serves as a mechanism for storytelling and recorded images, becomes a stand-in for the fragmented recollections of a young girl trying to piece together an image of her father years later. The imagery that Wells’ uses to emphasize how time alters perception, preserving and distorting a vital moment in Sophie’s life, is nothing short of sublime.

Additionally, while the TV is a haunting element, the books in the frame—titles such as How to Meditate and Tai Chi—further deepen the interpretative layers of the moment. Perhaps suggesting an attempt at some sort of psychological peace, self-discovery, or even escapism for Calum. But what if they’re just a splinter of Sophie’s memory? Maybe she wanted to remember her father as someone who was doing something to battle his demons.

The scene perfectly exemplifies Aftersun’s deeply personal excavation of love and loss. Calum, though present in the scene, feels distant, as if he is already a memory rather than a tangible figure. The use of reflections, darkness, and obscured perspectives serves to evoke a profound emotional response from the viewer, mirroring Sophie’s struggle to reconcile past happiness with her underlying grief. It’s a microcosm of the whole film, with Wells crafting a stirring moment that evokes deep pathos, materializing everything that preceded it and foreshadowing further what is to come later.

Through masterful cinematography and symbolic imagery, Charlotte Wells crafts a film that lingers long after it ends, much like the memories it seeks to depict. Something that clearly affected more than just me given the response to my tweet.

For those interested, here is our review of Aftersun on the podcast when it came out: