When he was born in 1908, Portugal was still ruled by a monarchy, only to be overthrown two years later. When he died in 2015, aged 106, Manoel de Oliveira had a career that touched everything in the history of cinema. His first half was under a dictatorship that kept him from going abroad and making anything he wanted and it was only after that government became a democracy did Oliveira come out of the shadows and into international consciousness. He lived through every change Portugal had during his lifespan and was still working when he died.

There was an industry of Portuguese movies, but none that had established lengthy credibility that Oliveira or others could follow, especially when the “New State” dictatorship took over in the late 20s and enforced strict censorship. He first studied as an actor, starring in one of Portugal’s first sound films, The Song of Lisbon, a film still considered among the best produced by Portugal. But after watching Berlin: Symphony Of A City, Oliveira turned to be a director, starting with his silent short documentary, Labor on the Douro River. While local critics hated it, international critics liked it. To make money, Oliveria did straight forward short documentaries while planning on his first full feature in 1942. That film was Aniki-Bóbó, a pre-neorealist film of two young boys who seek the heart of a girl they like. It was also hated, but it would age well in future decades where the film was also considered a classic in Portuguese cinema. (Below, the subtitles are in Spanish. Nothing in English.)

Again, because of the dictatorship, his next work would be another 12 years later with the color documentary short, The Artist And The City, focusing on a Portuguese artist and he prepares each idea by walking the streets. This time, it was well-liked and now work was coming to him. But those future works, Rite of Spring and The Hunt, got him in trouble with the censors and the government, and Oliveira was arrested by the secret police and jailed for 10 days. He remained constrained and under the strict eye of the “New State” regime until it was overthrown in a bloodless coup in 1974, transitioning to a liberal democracy today.

From then on, Oliveira would constantly produce work and become the symbol of Portuguese cinema, even in his 70s. Before the regime change in 1974, he would make the satirical Past And Present that assailed the bourgeoise as much as Luis Bunuel did minus the surrealism. Oliveira would go on to make a string of movies surround the theme of love astray within a sexually repressive backdrop, flaunting the content prohibited before now legalized with the times. He hit a high with 1981’s Francisca, which received global acclaim and was submitted as the country’s International Film nominee but failed to make the final five. His next movie was twice as long as The Irishman, a shocking seven-hour feature that took two years to make titled The Satin Slipper. It deals with similar themes as his other works set in the Renaissance and was Oliveira’s first production outside of Portugal. (If you have seven hours of free time and speak French, guess what?)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRODl8ebIp4

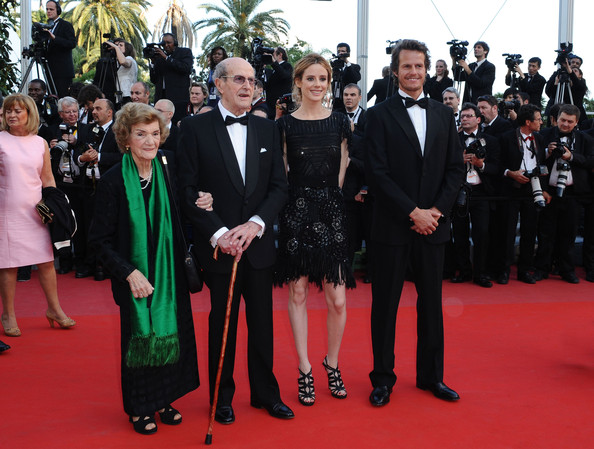

As he worked on throughout the 1990s, Manoel de Oliveira was getting complete international recognition for a lifetime of struggles and hidden masterpieces. His work was coming out in both Cannes and Venice Film Festivals, producing a stunning 10 feature films in the decade. Day of Despair, Abraham’s Valley, and Anxiety were the next films of his submitted as Portugal’s nominee at the Oscars but neither of those films broke through. His 1995 feature The Convent featured John Malkovich and Catherine Deneuve; 1997’s Voyage To The Beginning Of The World was the final movie of Italian acting legend Marcello Mastroianni and was released posthumously. 1999’s The Letter, made at age 91, won Oliveira the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes, while he would reunite with Malkovitch and Deneuve, along with Michel Piccoli who starred in his work from the 80s in 2001’s I’m Going Home. Oliveira would still not slow down as he approached age 100, making 9 feature films in the decade, including 2006’s Belle Toujours, a sequel to Luis Bunuel’s Belle de Jour, which again was submitted to the Oscars for the final time, but was not accepted.

Passing his centennial year, Oliveira, who started out with black & white with no sound, now moved over to digital color film for his last works. Gebo And The Shadow from 2012 was Oliveira’s final feature, as well as for noted French actress Jeanne Moreau. Upon his passing, Oliveira was in pre-production of a feature titled, The Church of the Devil. Married to his wife for 75 years (who also lived to be 100 before passing in 2019) with kids, grandkids, and great-grandkids around, the life and career of Manoel de Oliveira seem stunning, something that could only be written as fiction, yet here was a person that had memories of a world that changed generation to generation to generation. It’s a life of five acts, unknown and underrated to a chunk of general cinema viewers.

Follow me on Twitter: @brian_cine (Cine-A-Man)